The Demonic Origins of Ventriloquism

It may not surprise you to know that the popular entertainment has some very dark roots.

A ventriloquist and his dummy. (Photo: Everett Collection/shutterstock.com)

You might not think of Lamb Chop, the adorable hand puppet that graced the appendage of world-famous ventriloquist Shari Lewis or the impertinent wooden dummies operated by Edgar Bergan as having ancestors, but they do.

One of them is a snake in a human mask. But let’s back up.

Ventriloquism—altering your voice to make it sounds like it’s coming from somewhere else—is familiar to most as entertainment. Performers beguile audiences by making their voices seem like they belong to a dummy (or some other figure like Lamb Chop), chatting with their playful, inanimate partner. It was a smash on the vaudeville stage and stayed popular through the 60s. The heyday has passed, but there are still bold name acts like comedian Jeff Dunham, who tours the world and makes frequent television appearances, such as one on 30 Rock in which his character’s dummy calls Liz Lemon a “ferret-faced skank”.

But ventriloquism is not a modern art—it dates back to at least the classical Greece, when it really freaked people out.

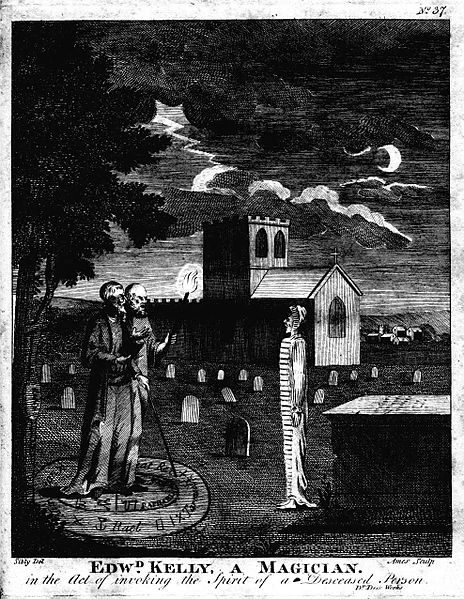

An engraving from 1806 showing ”Edw[ar]d Kelly, a Magician. in the Act of invoking the Spirit of a Deceased Person.” (Photo: Public Domain)

Back then, ventriloquists were called “engastrimyths”. Writes Steven Connor in his book Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism, this was a mashup of “en in, gaster the stomach, and mythos word or speech.” Basically, people believed engastrimyths had demons in their stomachs who belched words from their host’s mouths. Engastrimyths plied their trade for entertainment (what could be more thrilling than demonic tummy talk?) and as divination. Pioneering ventriloquist Valentine Vox writes in his book I Can See Your Lips Moving: The History and Art of Ventriloquism that the art’s roots lie in necromancy—the ancient art of allowing a dead person’s spirit to enter the necromancer and speak to the living.

Any way you slice it, the supernatural was involved. But back to the snake.

A medium conducting a seance in 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ggbain-03135)

In 150 A.D., a man called Alexander of Abonoteichus captivated contemporaries when he discovered a talking serpent with a human head. Not so captivated was the skeptical writer Lucian, who declared that the head was made from linen, mounted on a snake’s body, and made to speak through a tube operated by a concealed assistant. While not ventriloquism, it was an early use of a “dummy” to focus the audience’s attention on a miraculous voice. (Thankfully, animal carcasses have been phased out of modern interpretations.)

Fast forward a couple centuries, and voices from nowhere became associated with another unpopular trend—possession and witchcraft, both circumstances that tended to come with a lot of vocal acrobatics. Not surprisingly, this didn’t mean great things for ventriloquists. During the Reformation there was a nun named Elizabeth Barton in Kent whose ventriloquial prophecies were well-known. But when she uttered a supposedly divine statement that King Henry VIII shouldn’t marry Anne Boleyn, her popularity plummeted with the audience that mattered most—the king. Barton was hanged; Henry got married.

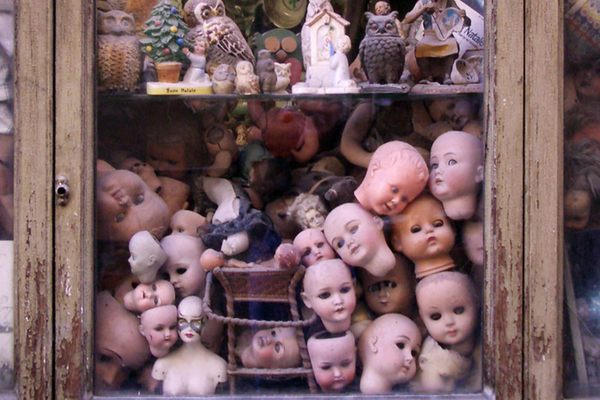

Christianity took a particularly dim view of ventriloquism in the 16th century, when witch trials swept through Europe, believing it was “to be regarded a practice spawned by hell itself” according to Vox. Disgruntled God-fearers believed mysterious voices emanated from any number of holes in the ventriloquists body—from the vagina to the nostrils. Sometimes even other animals found their way into the body. An account of the possession of a boy in 1500s England declared baying hounds could be heard in his stomach.

The titles in the trailer for the 1964 film Devil Doll. (Photo: Movieclips Trailer Vault/YouTube)

By the 18th century, ventriloquists were largely cleared of demonic dealings, and performers started drawing large European audiences. (Dummies still weren’t standard, and wouldn’t be until the end of the 19th century.) But people still looked askance at them—they could be tricksters, after all. An alarmed citizen wrote a letter to the New York Times in 1910 decrying the popularity of mediums who purported to speak to the dead, scofflaws the writer called “trumpet mediums” for a trick in which ghosts spoke through musical instruments and other means. “The trumpet medium,” declared the concerned party, “has as her confederate both men and women who are ventriloquists.”

Legendary Broadway critic Walter Kerr wrote of a 1977 Greenwich Village cabaret act featuring ventriloquism, “Do you realize what an ominous presence a ventriloquist’s dummy can be, often is?” He compared them to Frankenstein’s monster and the artist’s fear their creation could destroy them.

Filmmakers haven’t been able to resist musing on the horror of the dummy, either. A ventriloquist gripped with insanity appeared in 1945’s Dead of Night, and in 1964’s Devil Doll, a demonic dummy successfully swaps bodies with his master. Anthony Hopkins played a ventriloquist named Corky who commits murder with his animate dummy, Fats, in 1978’s Magic, and in 2007 the creators of the Saw franchise offered audiences Dead Silence in which an evil ventriloquist turns human victims into marionettes.

Big screen splatter-fests aside, today’s ventriloquists and their sidekicks have come a long way from suspicion and spirits.

After Lamb Chop’s creator, Lewis, passed away in 1998, her daughter Mallory continued performing with the puppet at fairs, art centers, and for military families. The precocious sheep was rewarded for this service when the marines made her a three-star general.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook