The Commune in Ethiopia Where Feminism is the Law

How a village in Ethiopia has come to serve as a model for the rights of women, children and the elderly.

The village center of Awra Amba. (All Photos: Zac Crellin)

Tucked away between the rugged gorges and valleys of the Ethiopian highlands is an egalitarian commune that defies the norms of traditional society. Awra Amba, founded in the utopian mold 44 years ago, has managed to thrive where so many other attempts have failed.

Awra Amba could be described as communist, puritanical, pantheistic, feminist, or even cult-like, but its 450 residents are wary of such descriptors. They believe their philosophy, as dictated by the community’s soft-spoken founder Zumra Nuru, is too easily distorted by cultural and linguistic differences to be labeled accurately by outsiders.

Nevertheless, four tenets do underpin the community’s way of life: respecting women’s rights, respecting children’s rights, caring for the elderly and vulnerable, and avoiding antisocial behavior. Today Awra Amba is governed by 13 democratically-elected committees, which cover everything from education to conflict resolution, taking care of orphans to village security.

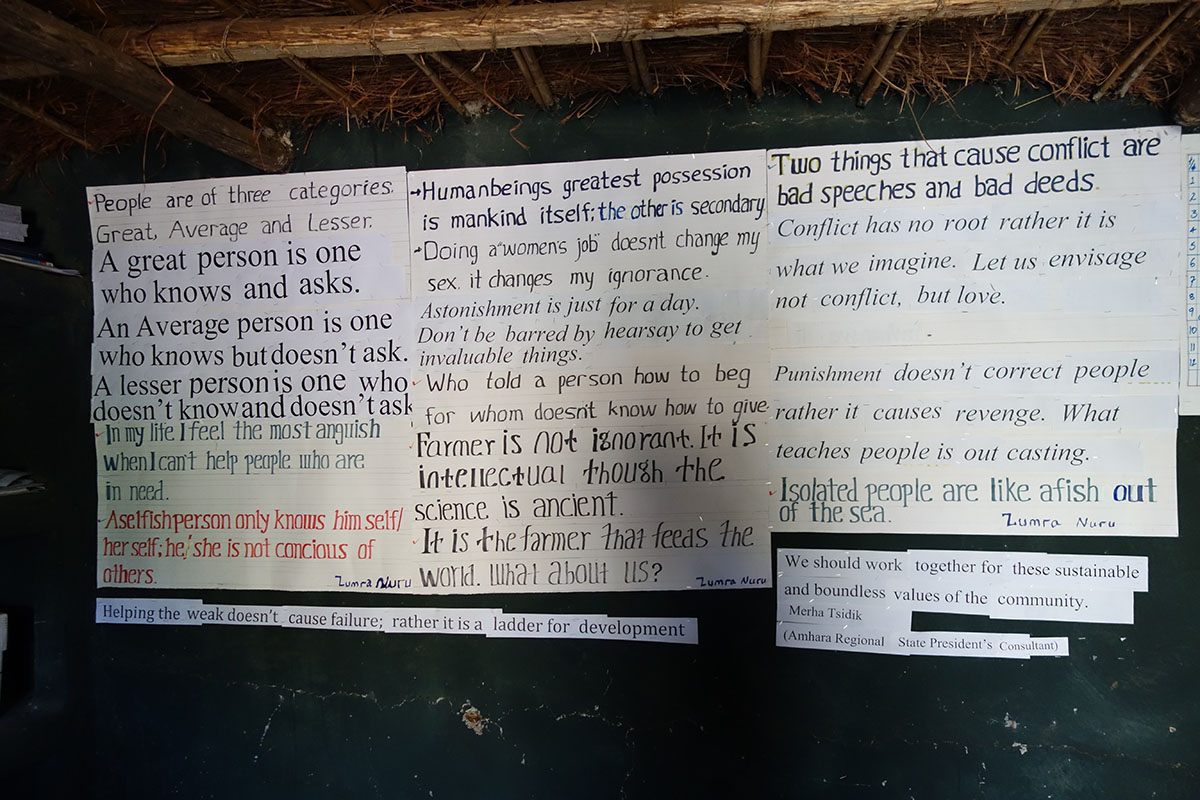

Zumra Nuru’s quotes are displayed in English and Amharic in the visitor reception building.

Much of the philosophy’s credibility stems from Nuru’s life story. It is said that at the age of two he began asking questions about inequality that were beyond the capacity of his family. Although he never received a formal education, by the age of four, the precocious child had formulated the four main principles of his belief system through observing the world around him.

“My mother and father were farmers,” Nuru writes in his manifesto. “In farming the land, they worked together. In the evening, when they returned home, my father was done for the day. But my mother’s work continued into the house. My mother’s duties were cooking wot, baking injera, collecting firewood, fetching water, nursing babies, washing my family’s feet, grinding grains by hand and more. These house tasks were my mother’s regular duties.”

Nuru left home and became a vagabond at 13, embarking on a desperate search to find like-minded people who sought to abolish cultural practices such as gender roles and child labor. He traveled from district to district, giving speeches to anyone who would listen. He says that for the next five years, people dismissed his ideas as idealistic and unfeasible.

A man herds cattle through the village.

Eventually, Nuru met a group of farmers in the lakeside district of Fogera who were receptive to his ideas. After meeting several times over many months, Nuru and the farmers established Awra Amba in 1972.

In a society which, like most, promotes rigid gender roles, Awra Amba is different. Gender equality is non-negotiable. Men are accountable for half the housework and child rearing, while women make up half the workforce in otherwise male professions such as plowing fields and weaving.

There is no shame or awkwardness for those performing these jobs. Customs dating back millennia have been eradicated in a single generation. One saying of Nuru’s is often repeated throughout the community: “Doing a ‘women’s job’ does not change my maleness—it changes my ignorance.”

The nursing home in Awra Amba. Rooms and care are provided free of cost, and the facility is the responsibility of the whole community.

Awra Amba functions using a two-tier membership system. Residents may choose to live by the village’s progressive social values as a community member, while others choose to go a step further and share their labor and income equally as a cooperative member.

Incorporating the farmers, weavers and miscellaneous jobs, the cooperative assigns work based on ability and divvies up its earnings annually. Everyone is welcome to participate in the cooperative, and the oldest worker is a cattle herder in his 90s. Each member receives the same income regardless of what job they do, and the remaining money is reinvested into the community’s industries. Around 150 of Awra Amba’s 450 inhabitants are cooperative members.

The equality promoted in Awra Amba was considered taboo by farmers in the surrounding region. They reported the villagers of Awra Amba to the authoritarian Derg regime, the communist military junta that ruled Ethiopia, accusing them of being members of the underground opposition. The villagers were eventually forced to flee in 1988.

A man weaves in Awra Amba’s textile factory.

The villagers were only able to return in 1993, two years after communist rule ended in Ethiopia. By that time, their farmland had been liquidated by the same people who had pushed them out. Starvation and disease crippled the community, and the death rate surged.

The community turned to textile production as a new source of income. This proved to be another exercise in gender equality, as weaving is traditionally a man’s job. The women of Awra Amba operate looms and traditional weaving tools alongside their male counterparts inside the village’s lone factory as well as at home.

One of the town’s strongest initiatives is its elder care. As a child, Nuru witnessed people collapse while working from health problems and old age. “These people are human beings just like we are,” he writes. “If we leave them behind when they need us, then perhaps in the future we may also be in their situation.”

The village’s elder care facility is the collective responsibility of the community. People who are unable to work are provided with free housing, food and care. The quarters are modest, but they provide safety, independence and dignity for those who live there. The project has been so successful that two members from outside of the village have been taken in as if they were the community’s own.

The kindergarten classroom in Awra Amba.

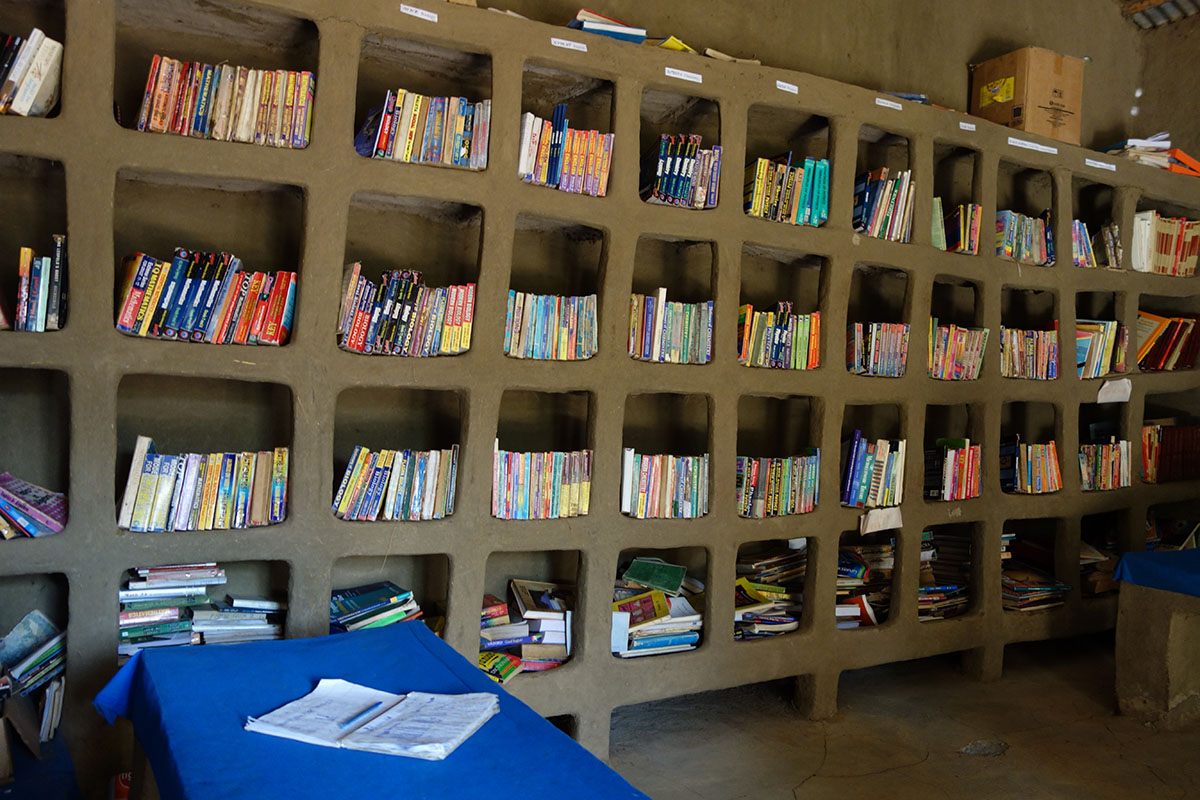

The rights of children are similarly respected in the community. Unlike some surrounding areas, no child is made to work and every child is entitled to an education. At the free, community-run school, children are encouraged to find both creative and logical solutions to social problems. They are also taught the community’s principles and expected to uphold them. At the end of each school day students recite a pledge not to steal, to be sympathetic towards one another, and to always work collaboratively.

Meanwhile, children’s ideas are respected and treated as equal to those of adults. Children may head fortnightly group discussions between families and neighbors which seek to resolve conflicts between individuals. Anyone can be elected to chair the meeting, and children are taught how to facilitate discussions in preparation for this. Zumra Nuru attributes his notions of equality to all humans being related:

“Humans have created the idea that we are not related if we are not from the same family. This notion brings about hostility; and hostility brings about quarrels. Human beings frighten other human beings just like ferocious animals. I thought if we could live by considering all human beings as sisters and brothers, there would not be any difference among human beings.”

The rooms inside Awra Amba’s nursing home.

As a village Awra Amba is humble, but the people take immense pride in their self-sufficiency, total equality and harmony. Nuru’s rigid social philosophy calls for the complete eradication of lying and insults alongside violence and murder. “Instead we should promote collaboration, honesty, love, compassion, humbleness, good heartedness, truthfulness, and peace,” he argues in his manifesto.

Keeping with this total commitment to harmony, sex before marriage is prohibited, as is the norm in rural Ethiopia. Drugs and alcohol are also banned, including such mainstays of Ethiopian culture as tej (honey wine) or khat (a natural stimulant). Divorce is allowed, and it is not restricted to exceptional circumstances.

Despite this deep sense of morality, the community is not underpinned by religion, but rather shuns it altogether. Instead, villagers adhere to a vague yet inclusive pantheistic spirituality, and don’t organize or express their spirituality in public. “I couldn’t understand why I should build a house in one particular place, where I could go inside to meet the creator if he was to be found everywhere,” Nuru writes, of why there is no church or mosque in the village.

Under this system, certain religious cultural practices have still persisted: some women wear loose hijabs while some men wrap themselves in white blankets worn by Ethiopian Orthodox churchgoers and pilgrims.

Awra Amba as seen from a hill.

Homes are modest in Awra Amba. Built in the traditional style of adobe walls with a wooden scaffold, they consist of two rooms: a kitchen and a living area. Fittings and furniture are made from a combination of one-part mud and three parts ash. Many homes house private looms, and while some residents can afford electricity or running water, most go without. This disparity is one side effect of the two-tier membership system.

Angelic photos of the “far-sighted honorable doctor” Zumra Nuru in his trademark green beanie adorn several buildings. His quotes are repeated as gospel, and villagers passionately refer to the founder as a genius. Residents are in awe of the fact that even when Nuru was a toddler, “his thought was concrete.”

However, Nuru does not exercise total control over the community. While most committee decisions respect the founder’s wisdom, there have been several occasions when community members have voted against his proposals. Positions on the village’s 13 committees are unpaid and elected triennially.

The library in Awra Amba largely consists of textbooks for students.

The key to Awra Amba’s success is its provision of freedom. While social rules are strict, villagers may come and go as they please and can opt-out of financial commitment. They are also encouraged to leave the village upon adulthood to broaden their horizons. Nevertheless, most residents return after only a few years to start a family.

Zumra Nuru hasn’t read Das Kapital, The Second Sex or the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child; he’s illiterate and completely self-taught. Awra Amba may closely resemble the ideas of philosophers and theorists from around the world, but its ideology has not been imported.

Instead, Nuru came up with pragmatic solutions to local problems, which are continuously developed and perfected through the combined effort of the community. People live humbly but harmoniously, and it is through this tradition that Awra Amba continues to flourish.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook