The Civil War Fighters Who Tempted Fate With North African Fashion

Why hundreds of Union and Confederate soldiers dressed for war in turbans, fezzes, and bright red pants.

“The Brierwood Pipe,” an 1864 painting by Winslow Homer, depicts two Zouaves from the 5th New York regiment. (Image: Cleveland Museum of Art/Public Domain)

The First Battle of Bull Run, in 1861, featured 40,000 barely-trained soldiers, shooting and yelling and rushing at each other in a mess of smoke and blood. In the middle of it all were the members of the 14th Brooklyn regiment of the New York State Militia, resplendent in their trademark crimson pants.

As they raced repeatedly up and down Henry House Hill in Virginia, the opposing general, soon to be known as Stonewall Jackson, gave them a new and appropriate nickname. “Hold on, boys!” the general reportedly yelled to his men: “Here come those red-legged devils again!”

The soldiers of the 14th Brooklyn hadn’t just grabbed any old trousers they had laying around. They were proud examples of the “Zouave Craze”: an unlikely military style that sent Civil War soldiers charging into battle wearing sashes, baggy pantaloons, tassled fezzes, and turbans. Forged in North Africa and co-opted by the French colonists, the Zouave style was taken to new heights by Union and Confederates alike—all thanks to one dedicated superfan.

The Zoauve dress and fighting style originated with the Zouaoua, a confederation of groups that lived in the coastal Algerian mountains. Zouaoua fighters had a reputation for fierceness and bravery, and for aligning their loyalties strategically within the always-shifting political terrain. After the French invaded Algiers in 1830, they recruited them to aid in colonizing the rest of Algeria, as a brand-new elite “Zouave Corps.”

Even as the Corps’s makeup changed—it was soon comprised mostly of European soldiers—its designation and ethos stuck around. Over the next two decades, the growing Zouave battalions became a fundamental part of the French army. The uniquely garbed soldiers played important roles in the Crimean and Franco-Prussian Wars of the 1850s and ’70s, and later in the opening battles of World War I.

French Zouaves colonizing Algeria, as depicted in an 1849 painting by Jean-Adolphe Beauce. (Image: Musée national du Château de Versailles/Public Domain)

Over the course of the 1850s, the Zouaves gained a number of stateside fans. Some saw them fight firsthand: while stationed as an observer in Europe during the Crimean War, future Union Army general-in-chief George B. McClellan called the Zouaves “the beau-ideal of a soldier.” “Of all the troops that I have ever seen, I should esteem it the greatest honor to assist in defeating the Zouaves,” wrote McClellan.

Others learned of their exploits from doe-eyed newspaper and magazine coverage, which painted the units as almost impossibly charming—roguish but disciplined, genteel yet ruthless, and unfailingly dramatic.

“If the Zouaves should be deprived by siege of their ammunition, they would fight with the butt end of their guns; if… they should lose their guns, they would throw stones; if there were no stones they would indulge in fistiana,” wrote the New York Times in 1860. “If their hands and feet were cut off, they would ‘butt’ with their heads and pummel with their stumps.”

The Atlantic Monthly told of how, faced with walking a group of prisoners across the desert, they “behaved like very Sisters of Charity, rather than rough bearded soldiers,” feeding orphaned babies with ewes’ milk and carrying exhausted old men.

French Zouaves in the First World War. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

But the Zouaves’ most evangelical overseas admirer was a young Illinois law clerk named Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth. Ellsworth had tried and failed to join the army, a difficult task for an inexperienced twentysomething during peacetime. Undeterred, he spent much of his workday dreaming of more direct combat, and his free time memorizing military manuals and making up new drills.

He also took fencing classes at a Chicago gym, where his instructor, Charles DeVilliers, happened to be a former Zouave. Tales of DeVillier’s exploits focused Ellsworth’s obsession, and soon, with his new mentor’s help, Ellsworth knew the Zouaves from A to Z. In 1857, he was named drillmaster of a local volunteer militia, the Rockford City Grays. Ellsworth taught them choreographed Zouaveian drill sequences, complete with flashy falls and gymnastic jumps.

“They would… crawl on their hands and knees as silent and quick as cats, [and] climb high stone walls by stepping on each other’s shoulders, making a human ladder,” wrote one admiring spectator.

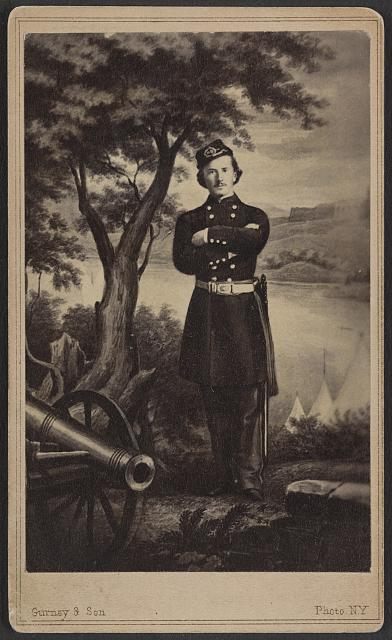

Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth, looking the part. (Image: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-35559)

Soon, militiamen and civilians alike were turning out to see the dramatic drills, and the enthusiastic Ellsworth was offered a sort of strings-attached promotion, as leader of the National Guard Cadets of Chicago. The Cadets had few members, were up to their epaulets in debt, and were on the verge of disbanding completely. Ellsworth renamed them the “United States Zouave Cadets,” and used the Algerian system to whip them into shape, drilling them with 23-pound backpacks on, and breaking slightly from Zouaveian tradition by insisting on a kind of “moral uprightness” that excluded drinking and carousing.

Ellsworth also designed his new regiment’s uniforms, which, in the words of one Cadet, consisted of “a bright red chasseur cap with gold braid; light blue shirt with moire antique facings; dark blue jacket with orange and red trimmings; brass bell buttons, placed as close together as possible; a red sash and loose red trousers; russet leather leggings, buttoned over the trousers, reaching from ankle halfway to knee; and white waistbelt.”

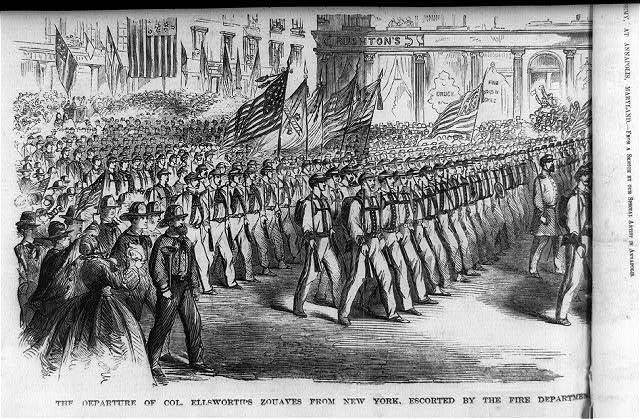

Ellsworth’s Zouaves marching triumphantly out of New York. (Image: Library of Congress/LC-USZ61-1819)

After a few months of practice, Ellsworth’s new and improved Cadets began appearing in public, dazzling the crowds with their multi-hued uniforms and well-tuned drills. They toured the entire East Coast, taking on challengers in drill matches and march-offs, and wowing spectators in Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and 17 other cities.

Ellsworth himself became a heartthrob: “Schoolgirls dreamed over the graceful wave of his curls,” wrote The Atlantic Monthly. Tens of thousands turned out to see his Cadets in New York, where, as the Times related, they made a proud, if historically inaccurate, showing: “a great success—an evidence of what can be done by patient toil, persevering system, and unflagging energy,” the paper wrote, “but by no means an exhibition of French Zouavism.”

American Zouavism was good enough for America, though, and as Ellsworth and the Cadets moved from city to city, they left scads of imitators in their wake. A so-called “Zouave craze” infected young men (and the occasional young woman) throughout the Union, who formed dozens, if not hundreds, of their own volunteer militias—complete with fancy drills, significant swagger, and uniforms that, in the words of military fashion expert Don Troiani, “reflected an originality of design that probably would have embarrassed a French Zouave.”

A Zouave ambulance crew demonstrates how to pick up wounded soldiers. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-cwpb-03790)

Meanwhile, Ellsworth, who had become friends with Abraham Lincoln back in Illinois and was now an Army Second Lieutenant in his administration, was tasked with an even higher-stakes assignment—raising up another militia, this time for actual combat. Ellsworth recruited from New York’s various volunteer fire departments and trained the recruits in his usual manner, and soon Ellsworth’s “Fire Zouaves” were marching into D.C. to meet the President.

Ellsworth finagled early action for the Fire Zouaves. In May of 1861, just hours after Virginia announced its secession, the unit joined a raiding party sent to retake the city of Alexandria for the Union.

Early in the raid, Ellsworth happened to see a Confederate flag waving from the roof of a hotel, and climbed up to take it down. As he left the hotel, banner in tow, Ellsworth was fatally shot by the innkeeper, James W. Jackson. In this way, the country’s premiere Zouave became the first conspicuous casualty of the Civil War.

A Civil War-era envelope memorializing Ellsworth. (Image: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-31825)

As the conflict raged on, and more of the country’s volunteer militias signed on for actual combat, American Zouaves earned their own battlefield reputation, made somewhat more complicated by the fact that they fought on both sides. Despite military brass’s efforts to standardize uniforms, both Union and Confederate regiments kept popping up in a diversity of red caps and flowing jackets.

Watching from overseas, the French press deadpanned “it’s raining Zouaves.” This was true, sadly, in more ways than one—their brightly-colored uniforms made them easy targets, and they tended to suffer disproportionate casualties. They saw action in every major battle up until the war’s end, and the Civil War’s last victim was also a Zouave, of the 155th Pennsylvania regiment.

In the later decades of the 19th century, the militia system gave way to the more organized National Guard, and most U.S. military fezzes, turbans and pantaloons were phased out for good. Today, American Zouaves show up mostly in Civil War reenactments, educating younger generations through dramatic performances while dressed in the uniforms of fierce guerrilla warriors from the Algerian mountains. Ellsworth would likely approve.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook