The Latin Typo That Gave Us the Temple of Ridicule

Ancient Rome never had an “Aedicula Ridiculi,” but plenty of people thought it did.

In his 1698 Dictionary of the Greek and Roman Antiquities, translated into English in 1700, the French abbot-scholar Pierre Danet dedicated an entire entry to an Aedicula Ridiculi—in English, Little Temple of Ridicule—in Rome. This chapel, he tells readers, was built on the spot where bad weather had forced the Carthaginian general Hannibal to give up on besieging the capital in 216 BC. “The Romans, upon this occasion, raised a very loud laughter,” Danet wrote, “and therefore they built a little oratory under the name of the God of Joy and Laughter.”

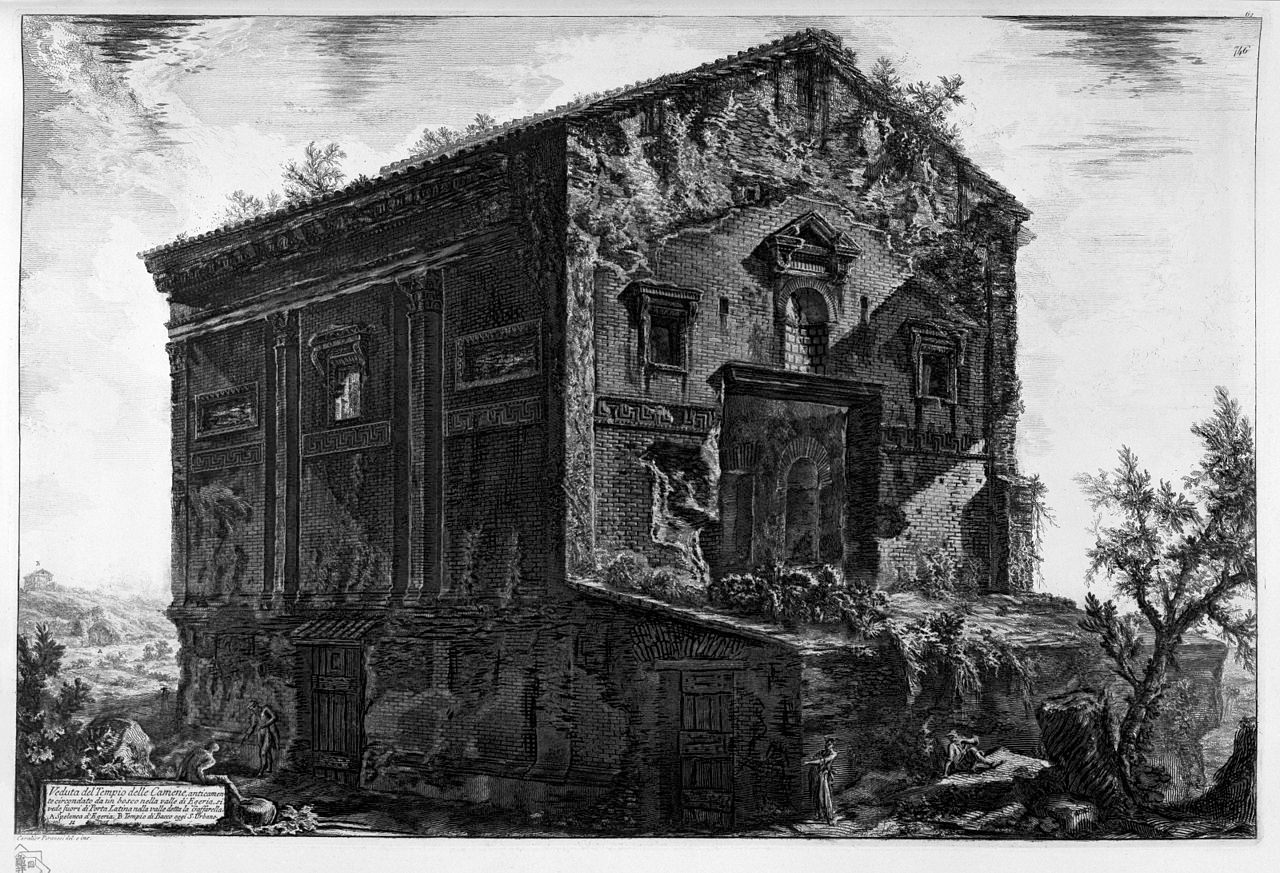

Danet gave the temple’s precise location (along the Appian Way, at the second milestone outside the Porta Capena), but trying to find it in a guidebook today would be an exercise in frustration. There’s a simple reason for this: It never existed. A rather beautiful Roman structure does stand on the site he described, but it’s not a temple—instead, it’s now widely believed to be the tomb of a woman named Annia Regilla, who died nearly 400 years after Hannibal’s invasion of Italy. To give Danet some credit, he was far from alone in making this mistake.

Despite being fake, the Aedicula Ridiculi was commonly treated as fact in the early encyclopedias of Roman ruins put together by pioneering Italian and French antiquarians of the 16th and 17th centuries, including Bartolomeo Marliani, Onofrio Panvinio, and Jean-Jacques Boissard. Even after being debunked by archaeologists, the Temple of Ridicule would continue to pop up for centuries in texts written for general audiences as a fun factoid: As late as 1852, an essay on the history of wit in Dolman’s Magazine notes, as evidence that humans have always valued humor, that “the ancient Romans went so far as to erect a ridiculi aedicula, or chapel of laughter.”

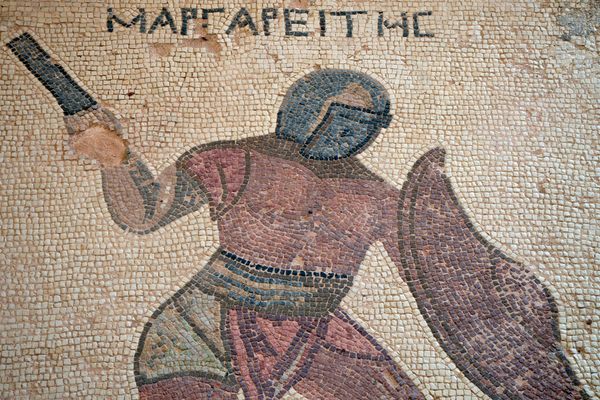

It’s simple enough to understand how rumors of the temple took hold. Only two ancient texts are ever cited as evidence for its existence. The first is Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, which mentions in a section on birds that a shoemaker once buried his beloved pet raven “on the right-hand side of the Appian Way, at the second milestone from the City, in the field generally known as the ‘field of Rediculus’” (in Latin, campus Rediculi). The second is a fragment written by the second-century grammarian Festus: “The temple of Rediculus [fanum Rediculi] was outside the Porta Capena; it was so called because Hannibal, when on the march from Capua, turned back at that spot, being alarmed at certain portentous visions.”

It isn’t necessary to understand Latin to pick up on a big clue here: Instead of Ridiculi with an “i,” both ancient sources say Rediculi with an “e.” That one-letter difference is important. While Ridiculi is indeed a form of the Latin verb ridere, to ridicule, Rediculi comes from the totally unrelated redire, to turn back or retreat. In this light, the Temple of Ridicule starts to look like a typo that took on a life of its own.

Small spelling mistakes that radically change the meaning of words are extremely common in medieval copies of ancient texts. As a result, classicists practice textual criticism, the meticulous and sometimes contentious comparison of differences in all known manuscript copies of a certain text. Once all variants have been catalogued, scholars cobble together an authoritative edition that approximates the original text as closely as possible. This process was only completed for the notoriously long and thorny Natural History over the course of the 19th century. Tellingly, at the spot in the text where most copies have the correct rediculi, the French monk who, shortly before the year 900, transcribed one of the oldest relatively complete manuscripts of the Natural History wrote ridiculi, “of ridicule.”

As classical scholars became more aware that medieval copies of ancient texts were often riddled with spelling errors, the reading Rediculi, “Retreat,” became preferred in learned circles. Aside from being better attested in the scattered manuscripts, it made more sense in context: Neither of the ancient sources mentions laughter, but Festus at least includes the story of Hannibal’s retreat.

While the popular Italian name for the building remains the Temple of Rediculus (with an e)—the official website of the Caffarella Park, within which the ruin sits, describes it as “the traditional name”—both spellings ultimately became moot. Improvements in archaeological science led to greater accuracy in the dating and identification of ruins, including the brick structure at the second milestone on the Appian Way. “The pretended aedicula ridiculi,” the architectural historian Robert Stuart confidently (and correctly) wrote in 1830, “is nothing more than a tomb of the lower ages.”

The myth of the Temple of Ridicule was not yet totally vanquished. Its most persistent defenders were the semi-professional tour guides called ciceroni (an ironic reference to the learnedness of the Roman orator Cicero), who had a stranglehold on the Italian tourism industry well into the 19th century despite a reputation for dubious accuracy. The American novelist James Fenimore Cooper complained about the “ignorance and knavery” of these ciceroni, but still hired one when he toured Rome in 1838. The tour guide’s influence is obvious in Cooper’s account of visiting a temple commemorating Hannibal’s retreat. “The term ridiculous,” he wrote, “is universally applied to the building.”

Another reluctant employer of ciceroni was the American magazine editor and poet Nathaniel Parker Willis, who echoes the legend in his 1835 travelogue Pencillings by the Way. “The dedication of a temple to ridicule is far from amiss,” he wrote after visiting the site, considering how powerful a force ridicule can be. “In our age particularly,” he quipped, “the lamp should be relit.” Willis’s reverie offers a glimpse into why the false identification endured long after it went out of fashion among academics: It was accessible to tourists with little knowledge of or interest in the details of Roman history, and, maybe more importantly, it gave them the opportunity to make their own jokes with other tourists, with ciceroni, and among friends (or in travelogues) back at home.

In the end, the Temple of Ridicule crumbled under the weight of historical evidence even in the travel genre. “We cannot avoid pointing out,” wrote the author of a review of Willis’s book in the London and Westminster Review, that the temple “has nothing to do with ridicule.” This harbinger of higher standards in tourism literature is laudable, but has its own subtle irony. “The common guidebook,” the reviewer smugly went on to add, “would have enabled Mr. Willis to avoid this error.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook