Stunning Photos of a Siberian Gold Mine Only Accessible by Air–Or Ice Road

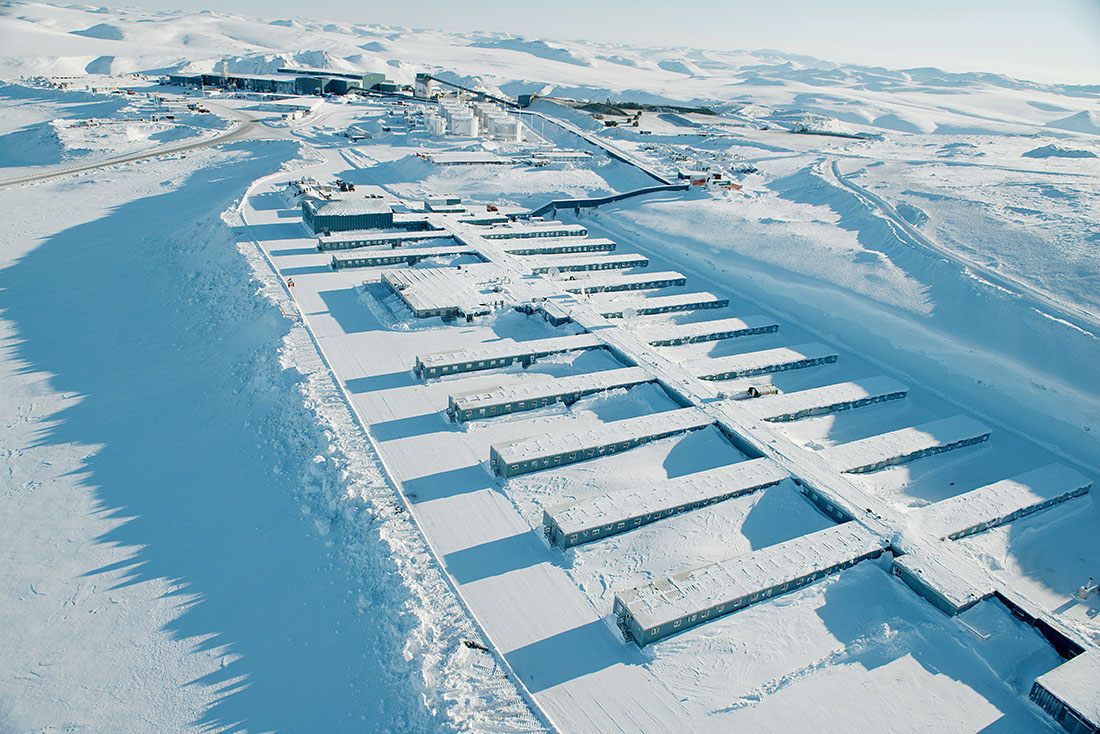

The Kupol Gold Mine, nestled in the desolate landscape of eastern Siberia. (All Photos: © Elena Chernyshova)

Above the Arctic Circle, near the East Siberian Sea and far into the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug of Russia, is the Kupol Gold Mine. It is located in a notoriously isolated part of the world. Under Stalin, gulags were established in the region, many of which were used to mine for natural resources. Deposits of gold were first discovered in the 1940s. In 2005, construction began on Kupol.

The gateway city to Kupol is Magadan, once the administrative center for the forced labor camp system. From Magadan, it’s still a two-hour flight across a frozen landscape to reach the mine. Provisions for the 1,200 workers who live there are ordered two years in advance, and then carried along the 220-mile ice road that only exists between January and April. The rest of the year, Kupol is just accessible by air. In winter, temperatures there can drop as low as -31 degrees Fahrenheit.

Yet within this hostile climate, the mine, which produces gold and silver doré bars, functions as a both a workplace and a home. Its facilities include a gym, a billiards hall, and a library. There is a rock band of workers that plays at the café, and a greenhouse for fresh salad.

Russian photographer Elena Chernyshova stayed at Kupol for 10 days to document the mine. Her photographs are a captivating study of humans working in unusually challenging conditions. Atlas Obscura spoke with Chernyshova about her time there, the appeal of shooting at “a lunar station in a lifeless landscape,” and the complicated logistics of making art in one of the world’s coldest and most remote regions.

The flight from Magadan arrives.

What appealed to you about traveling to Siberia in winter to photograph a vast mining operation?

I am very interested by the Northern areas of Russia, industrial explorations, and the lives of people in these conditions.

The idea of this project began with journalist Andrey Jouravlev, who worked for National Geographic Russia. He met airport workers from the Kupol gold mine, and was impressed by their stories about their work process, maintenance of the complex in such complicated climate conditions, and isolation. He knew of my work about Norilsk [the world’s northernmost city of more than 100,000 people], and that I had experience working in cold weather conditions and on industrial sites, and invited me to join him to work on this story.

Given its remoteness and temperatures, how did you travel to the mine, and what was the journey like?

Kupol gold mine is situated in the region of Chukotka, in northeast Russia, just opposite to Alaska. There are no roads linking the site with other regions of Russia. To get there we took a flight from Moscow to Magadan. Than we had to take a company airplane that brings the workers to the site. The flight takes two hours.

The airplane was quite small and had just a few windows in the front and back of the aircraft cabin. You can hear loud engines but can’t see outside. When we were landing, the pilot allowed me to stay in the cabin and take photos. It is magical– white deserts with the soft rose light of sunrise. The Kupol mine resembles a lunar station in a lifeless landscape.

When we arrived at the site’s airport, the bags of every passenger were scanned–it is forbidden to bring alcohol to the site. If it is found, a worker can be dismissed directly.

The ice road between Kupol and Pevek that brings provisions to the camp. It has to be reconstructed each year between November and January.

How long did you spend photographing the mine?

I stayed 10 days on the site. It’s a very big complex. During my stay we visited Kupol, the factory, and Dvoinoye, a mine 100 kilometers away. We had also a chance to drive along the winter road that links Kupol with Pevek, an international port on the Arctic Ocean, the main logistic artery of the company.

Kinross [the company that owns the mine] creates this road every year for six months during the winter period. During this period it is possible to bring in all 4,000 containers and 60,000 tons of oils and lubricants that accumulate in the port during the short navigation period. The whole route is marked by reflective pegs and road signs, and the roadbed is cleaned of snow and constantly renewed: refrozen with the help of sprinkler wagons where water is heated by a tail pipe.

The sleeping quarters for Kupol’s employees.

What kind of preparations did you need to make for your equipment, and for shooting in limited hours of daylight and underground?

I had no particular preparation. After my experience in Norilsk, where I had to shoot sometimes in -45 degrees, or +95 degrees in the sauna, or 800 meters under the ground, I have a certain confidence to my camera.

It is more important to prepare yourself, to be really well dressed. On the site people gave us additional coats and pants to make sure we never got cold. The most complicated is the protection for hands. I had several gloves of different thicknesses, so I could change settings on the camera.

It is important to have several batteries: with low temperature the power goes fast. When the battery expired, I warmed it in the inner pocket so I could use it again. I had two cameras, one for shooting outside and another for inside. When we went from the low temperature inside, it was important to put the camera in a hermetic bag and give it time to adapt to warm temperatures, to avoid condensation that can damage the electronic system. For the low light, it is good to have a tripod for working in dark industrial spaces. There are lots of sources of light from big machines that can create very beautiful scenes.

The ping-pong recreation area.

How deep into the mine did you travel? Many people would find this terrifying–what was that experience like the first time you did it?

I have been 400 meters underground. I love this experience, and find it thrilling: long dark tunnels with bright spots of light from our car, unexpected spaces of excavation, huge machines that drill or dig, that if necessary, can be operated with the help of the remote console. The scale of work is impressive.

The Kupol mine is owned by Canadian company Kinross.

Into the mine.

Kupol produces both gold and silver, and produced its first gold ore in 2008.

Photographer Elena Chernyshova travelled 400 meters underground to document the mine.

What was the atmosphere among the miners, given the language barriers, close living conditions and intense work schedule?

I found the atmosphere very positive. People are friendly. The working days are intense and hard, but the company provides possibilities to have a good rest. Workers stay on the site for two months, afterwards they have two months of rest. The working day is 12 hours, no weekend.

Life conditions are good: the company provides food with a wide choice of dishes, cleaning of rooms, and clothes. During their free time workers can go to the gym, play mini-football, billiards, ping-pong, watch TV, and there is even a rock cafe where a rock band of local worker-musicians plays. There is a good internet connection, so they can be connected with their family and friends.

Among the Russian and Ukrainian workers, did any of them share stories of Soviet-era mining vs. present-day Kupol?

People remember the Gulag era and gold exploration under Stalin well, but it is not a usual topic of discussion.

Was there anything about the mine that you weren’t expecting?

I was not expecting to see a garden of hydroponics that provides up to 25 kilograms of greenery a day for the canteen.

The prayer room.

The full-site gym on-site at Kupol.

A rock band comprised of workers plays at the cafe. There is internet so that the workers can stay connected. Alcohol is entirely banned.

In the kitchen.

The hydroponic greenhouse providing some fresh produce for the workers at Kupol.

Working in the frozen landscape. The growing season in the Chukotka is short, around 80-100 days per year.

Footsteps in a desolate landscape.

A beautifully frozen vista.

An aerial view of Kupol and the workers camp. There is a 900-meter enclosed tunnel that connects the camp to the mine, known as the “Arctic Corridor.”

By night, under the Northern Lights.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook