The 19th Century ‘Show Caves’ That Became America’s First Tourist Traps

Novelists concocted elaborate fake histories for mysterious caves in Virginia.

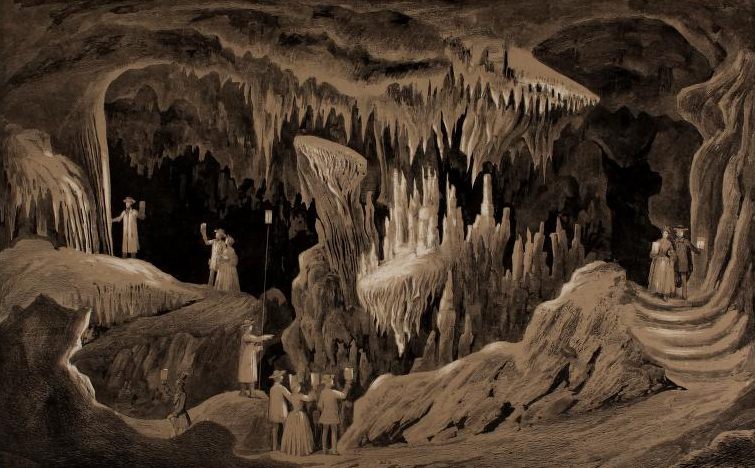

An illustration of Weyer’s Cave from 1858. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

A cave is a perfect mystery: dark, dangerous, and filled with pristine evidence. The caves underneath western Virginia attest to million-year geological transformations, but they also harbor intrigue on a human scale. The discovery of these subterranean wonders in the 1800s spawned a genre of local lore and popular fiction–call it “the romance of the cave”–in which crystal caverns became theaters for passion and politics.

Many cave romances were European fantasies of ancient North America, featuring stereotyped Indians as well as mythical races like Phoenicians and lost tribes of Israel. Caves became gateways to an imagined past for a country with a very short recorded history. Meanwhile, centuries of tourism and amateur exploration have destroyed archaeological evidence that could have revealed a more realistic story of early Native American cultures.

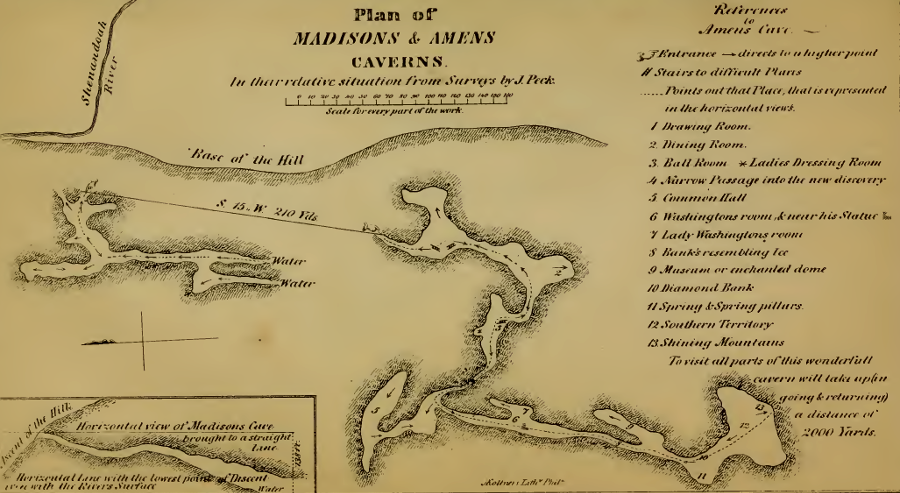

Virginia was a hotspot for cave exploration even in colonial times. Thomas Jefferson mapped caves in the state’s Valley and Ridge province in the 1780s–and found some that had already been tagged by a teenage George Washington forty years earlier.

Thomas Jefferson’s map of Madison’s Cave, from Notes on the State of Virginia. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

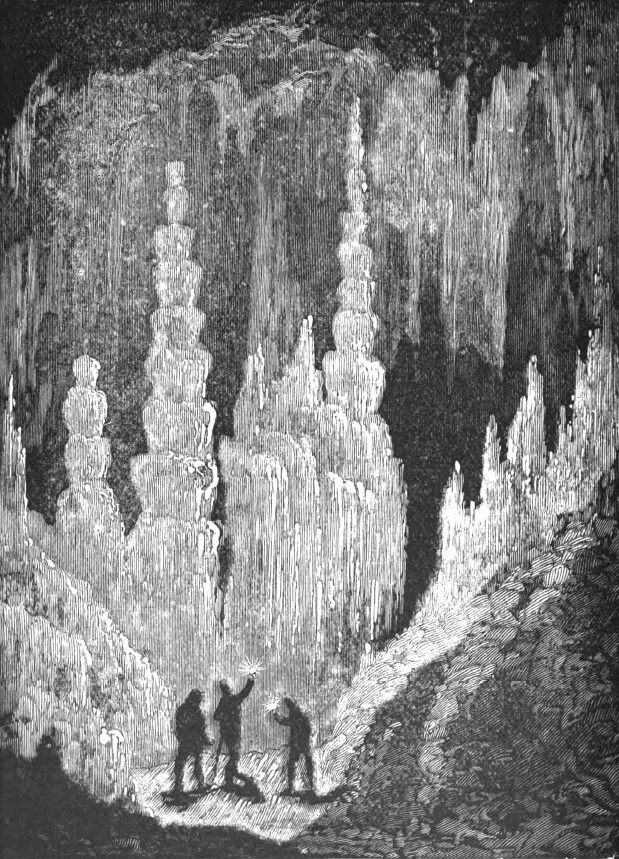

These finds were only a teaser for Weyer’s Cave, discovered by a fur trapper in 1804. Weyer’s was more spectacular and easier to access, especially after its owner built walkways and stairs for visitors to wander safely amid a “sublimity and grandeur…not surpassed by anything in nature.”

Most of Virginia’s more than 4,400 documented caves are hidden in the wilderness. However, once enterprising landowners realized that they could develop larger caves into tourist traps, there was a rush to capitalize on this geological wonder. A new and enduring category of roadside attraction, the “show cave”, was born. The discovery of additional sites, such as Luray Caverns in 1878, kept the fascination alive for generations of Americans.

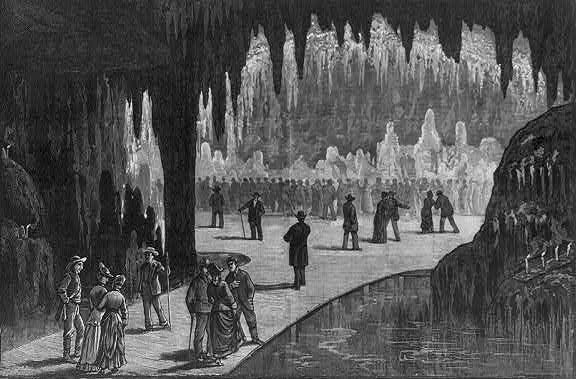

The scene at the cave at Luray, December 27, 1878. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-78687)

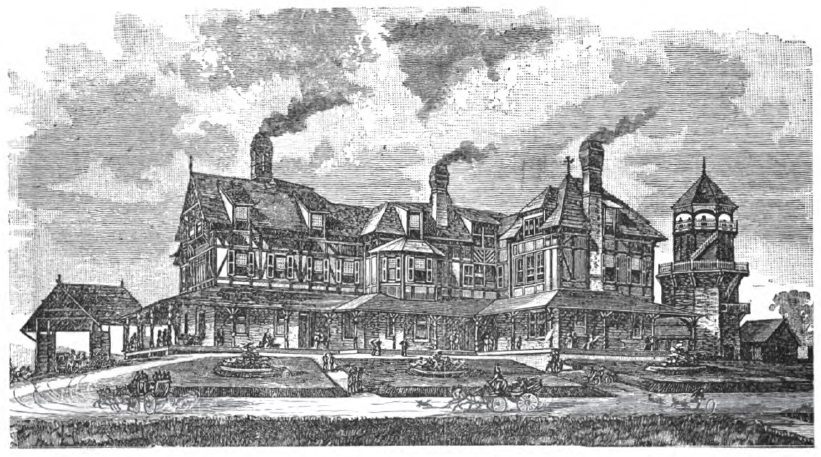

The show cave business took off thanks to the 19th-century expansion of railroads; for instance, the Shenandoah Valley Railroad Company bought Luray Caverns in 1881. They developed package tours, built a hotel, and ran electric lights into the cave. Advertising it as a luxury vacation spot, the railroad boasted that a visitor could “spend hours wandering underground without wetting his feet.” Even during these boom times caves competed fiercely for tourist dollars, with big players like Luray and Weyer’s putting humbler neighbors out of business.

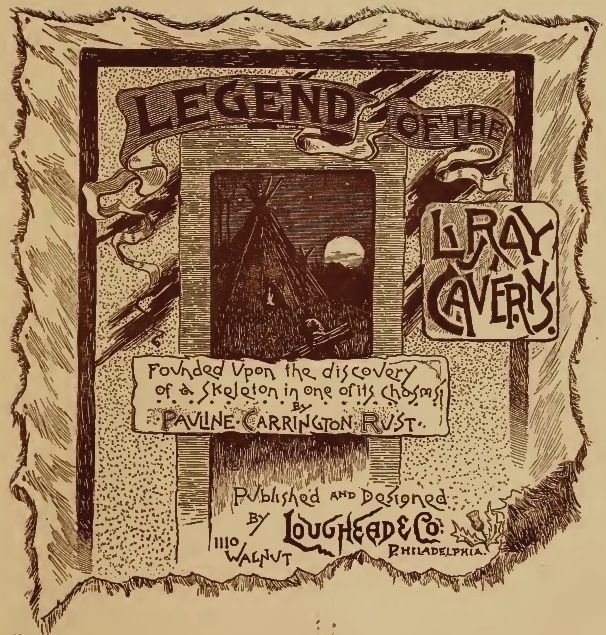

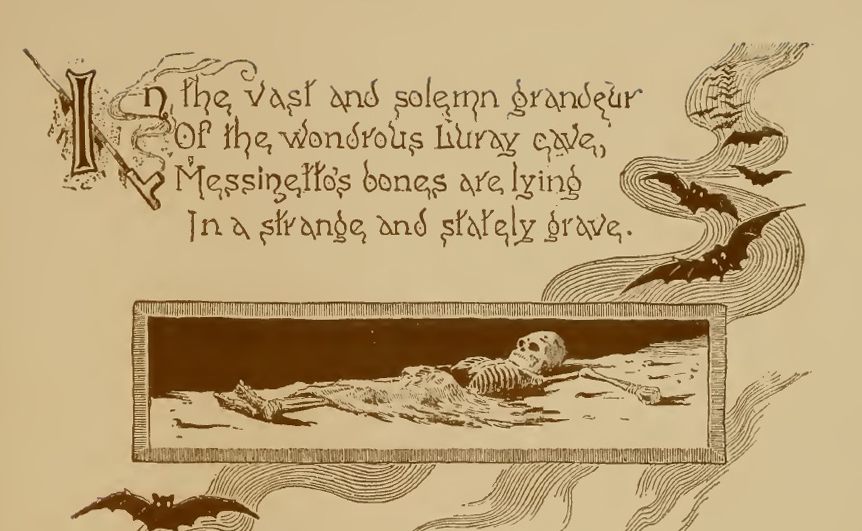

In the midst of a national love affair with caverns, writers wasted no time incorporating this theme into plot lines–and sponsorship from railroads didn’t hurt. An early entry in this genre is the 1887 illustrated poem, Legend of the Luray Caverns. Its author, Pauline Carrington Rust, took a human skeleton discovered in the cave as inspiration for a tale of forbidden love. The story’s hero is an Indian warrior who, “false to squaw and sire and race,” carries on a tryst with a white woman. As punishment for his betrayal, his tribe throws him into the cave to die of starvation.

The guided tour of Luray Caverns soon included a visit to his bones, half-buried in “Skeleton Gorge”.

A sentimental poem from 1887 provided an origin story for the skeleton discovered in Luray Caverns. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

The tale ends with the discovery of Luray Caverns by white tourists: “the hurrying tread of an eager throng / breaks rudely on the silence of the dead.” Though adopting a common 19th-century tone of wistful nostalgia for the “vanishing Indian”, Rusk remained just as oblivious as Luray tourists to the actual history of Virginia’s Native American peoples.

Six years later, a novel titled Arsareth: A Tale of the Luray Caverns served up a more elaborate mythology: that the caverns once sheltered a lost tribe of Israel. The heroine of this romance, set in the 1830s, enters a trance state and travels through time to eavesdrop on some wandering Israelites as they bury their treasure in Luray. Her psychic vision proves accurate: she draws up a map with the help of a Ouija board, and the treasure is really there. Conveniently, the cave’s bounty frees her to marry the man she loves instead of an abusive plantation owner.

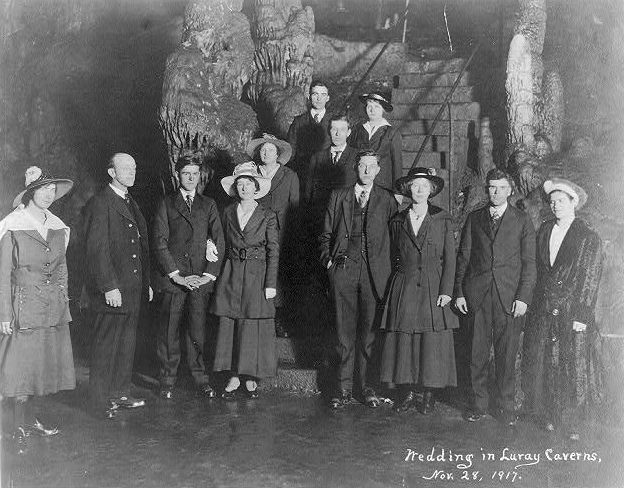

A wedding in Luray Caverns, 1917. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-38034)

Arsareth drew on widespread scholarly and not-so-scholarly speculation that North America was originally populated by Israelites, Hindus, Egyptians, or another exotic race. These theories conveniently dispossessed living Native Americans of their claim to the land, which was one more reason for their popularity. With little archeological study devoted to North American sites, such theories were mostly armchair conjecture.

Caves did contain solid evidence in the form of bones. 19th-century physiognomists examined skulls to determine the identity of people buried in caves, but their subjective methods produced more controversy than consensus. Nevertheless, skeletons found in show caves became part of the tourist experience. They helped people vividly imagine a world before electric lights and souvenir spoons.

Americans flocked to caves as gateways into ancient history, but proceeded to fill these mysterious hollows with their own version of the past.

The Shenandoah Railroad Co. purchased Luray Caverns in 1881, and constructed the hotel pictured in their 1889 guidebook. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

In 1922, the proprietor of Luray Caverns decided, whether for publicity or for the sake of science, to call in Smithsonian Institution anthropologists to dig up the resident skeleton of “Skeleton Gorge”.

Dr. Ales Hrdlicka returned to his museum in Washington toting the entire stalagmite formation in which the bones were embedded. Hrdlicka was disappointed to find no skull fragments among the remains. This could have confirmed the skeleton’s geographic origin and offered proof for Hrdlicka’s theory that Native Americans entered the continent via a land bridge from Asia many thousands of years ago.

The romantic hero of Rust’s poem didn’t get respectful treatment from cave tourists; the remains were repeatedly vandalized. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

Even without a skull as evidence, the Luray Caverns Corporation decided that the namesake of Skeleton Gorge was, indeed, an Indian rather than an ancient Israelite. However, they produced a new fictional biography of this hero that made him into a prophet of Christianity–again catering to the persistent logic of manifest destiny. Perhaps the proprietors were trying to compensate for the loss of the actual skeleton with this 1922 tale, which dubbed him “Tongo” and told of his sacred quest for the “Great Spirit” in the depths of the cave.

The story of Tongo, and of Hrdlicka’s excavation, put Luray back in the national news just as domestic tourism entered a post-World War I boom. Millions of middle-class Americans bought cars and flocked to novelty roadside attractions from the 1920s through the 1950s. Science noted in 1922 that Virginia’s limestone belt was “traversed yearly by thousands of automobile tourists, and no one has adequately seen America who has not visited one or more of the caverns of the Shenandoah Valley.”

Guidebooks gave each area of the cavern a fanciful name, like Giant’s Hall, pictured here. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

The romantic melancholy of bones embedded in crystalline dripstone, melding with the earth’s very crust, may have inspired more writers than it did scientific investigators over the past 200 years. Preserving and interpreting cave sites has been low on the list of archeological priorities. A team of archeologists reported in 2001 that, of the 52 identified cave burial sites in Virginia, only one had been professionally excavated.

In a plea for better preservation, they warn that endangered caves containing human remains hold valuable clues to the Native American Woodland cultures that thrived between 1200 BCE and the arrival of Europeans. Careful digs can reveal what ancient people ate, what diseases they suffered, and hint at religious beliefs that shaped their treatment of the dead.

This archeological record speaks a language very different from the sentimental cave romances of the 1890s.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook