Does Everyone Really Order the Second-Cheapest Wine?

An investigation into happy-hour folklore.

It takes a village to sell a glass of wine. A winemaker carefully monitors weather patterns and directs the harvest, a designer creates an avant-garde pattern for the label, and a restaurateur writes tasting notes on a tasteful menu. But, in the end, the wine that someone chooses with dinner may be influenced most by a single factor: price.

In April, we wrote about the second-cheapest wine phenomenon. The idea is that many diners—feeling unsure about the difference between wines, or skeptical that they’d really notice the difference—want to just order the cheapest one. But since that seems stingy, they choose the second-cheapest choice instead. It’s not a universally known idea, but plenty of people joke about choosing wine this way.

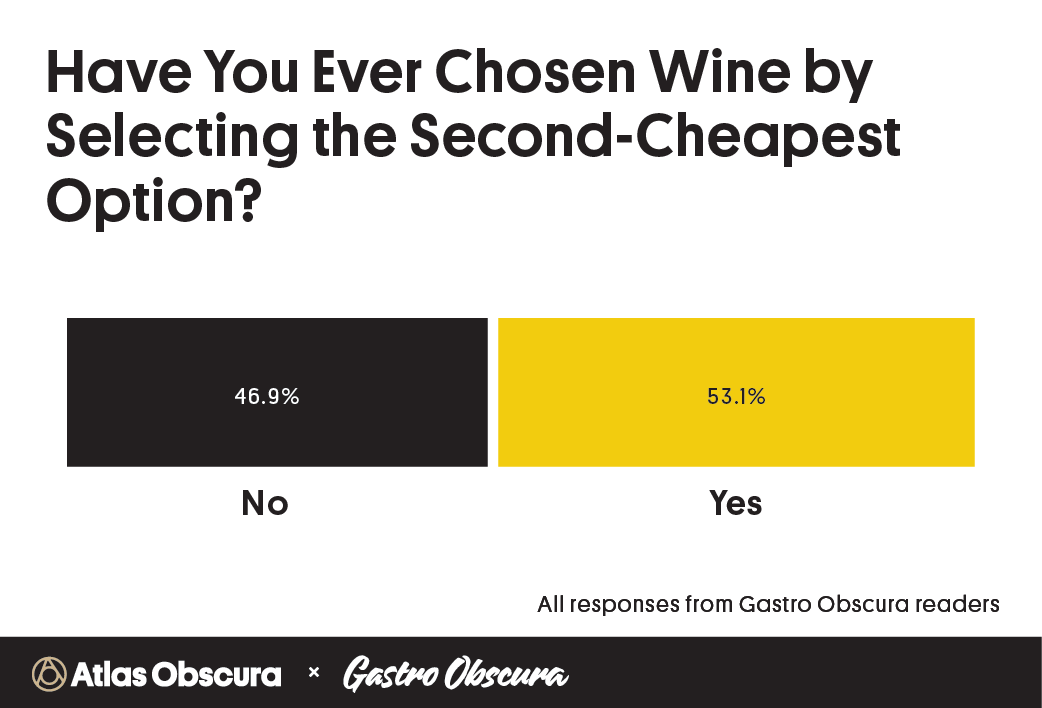

We recently asked Gastro Obscura readers for help investigating this phenomenon. We wanted to know how many people actually order wine this way, and whether it leads bar and restaurant managers to choose their second-cheapest wine with extra care. And the results are in: Over half of the 304 readers we heard from have ordered wine by choosing the second cheapest. It’s definitely a thing.

During this investigation, we heard about many rules of thumb for choosing a wine. Plenty of people look for a favorite variety (pick the Riesling!) or ask the waitstaff for suggestions. Some strategies are more unorthodox. “If there’s a horsie guy (rider on a horse) on the wine label, then I get it,” writes Jackie Benton of Austin, Texas. “If there are no riders on horseback, no horses, and no ladies to be found on any of the wine labels, then I embrace being my father’s daughter and switch to whiskey.”

Despite wine’s romantic image, though, price proved to be a bigger priority for many readers. “I go for cheap, thinking that any decent restaurant would not serve up a truly bad wine,” writes David from Milwaukee. Others committed to a price point that feels right. “I love Malbecs,” writes Cecilia from Los Angeles. “I wouldn’t want to pay $18 a glass, and $9 feels too cheap. But $11 somehow feels right.”

In an example of how much we can psych ourselves out over wine, Jennifer Tharp, of San Francisco, writes about why she picks higher-priced wines recommended by the sommelier or waitstaff:

I usually want to convince myself that I have ordered the best wine I could. I know I probably would like the second-cheapest wine just fine. But if I order a cheaper wine and hate it, I would blame myself for being cheap. If I order an expensive wine and hate it, then it feels like it wasn’t my fault.

And then, of course, there’s the classic second-cheapest wine approach:

I have to admit that the rationale you mapped out is correct. I am self-shamed into getting one a step above the cheapest. And yes, I know absolutely nothing about wine. Except that I tried a good Pinot noir once and am very fond of it. —Mark Strouthes, Arnold, Maryland

I order the second cheapest because I secretly want the cheapest, but then I decide to treat myself and splurge the one dollar. —Hannah, Denver, Colorado

I like wine, but I’m thrifty. I have found many “second-cheapest” brands and vintages I thoroughly enjoy. This way of selecting wines works for me while shopping and at restaurants. I have drunk some very expensive wines that were a real treat, but I would never buy them myself. Second-cheapest is a lifestyle I embrace enthusiastically! —Caren Helms, Raleigh, North Carolina

I didn’t even know I did it until this article! I do it so I look like I put some thought into the decision and avoid looking cheap. —Kristen, Detroit, Michigan

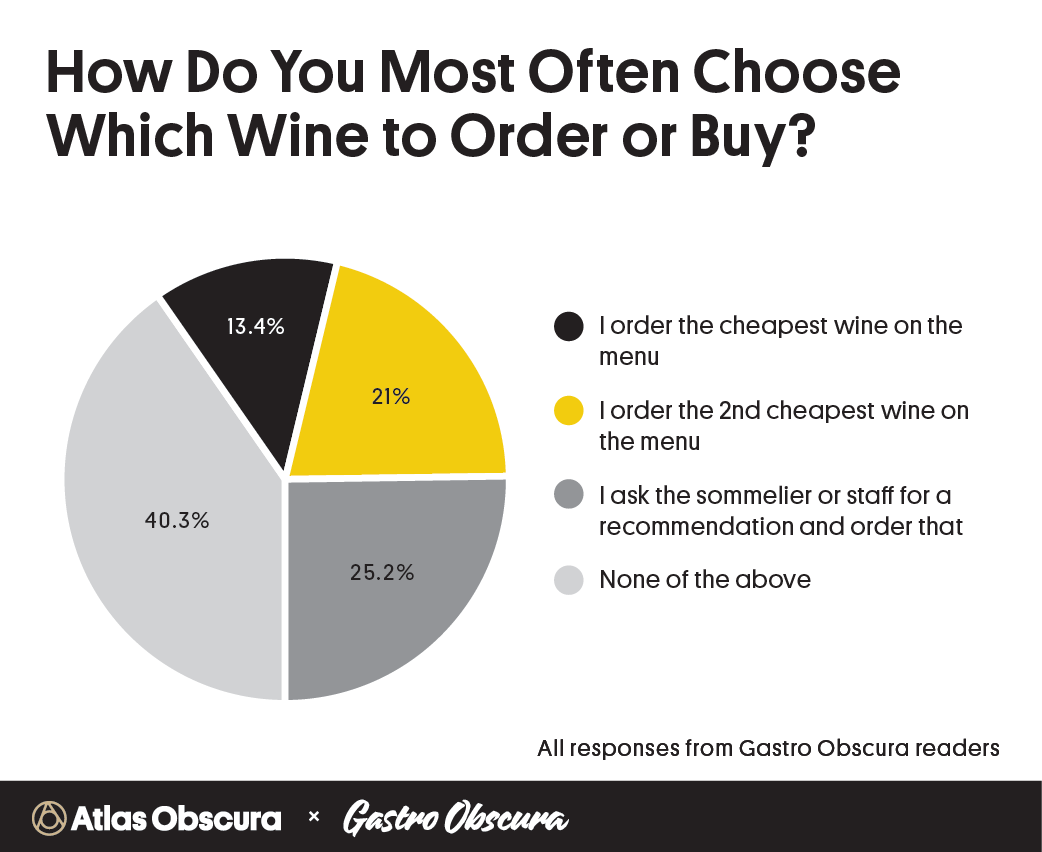

So just how often do diners pick a wine by choosing the second-cheapest? According to our reader poll, just over 20 percent of people say it’s their go-to strategy:

The second-cheapest wine approach doesn’t stand out here—it’s less commonly used than asking the waitstaff for recommendations. (For the survey, we asked people how they chose after deciding on a variety or whether to pick red or white.) But over 50 percent of our respondents have used it before, and over 20 percent use it regularly. So while it may be hard to notice among the general trend of diners choosing cheap wines, bottles of the second-cheapest wine should go dry faster than chance would predict. Especially if the wine list is long.

Bar and restaurant managers have noticed. “I’m a sommelier now, but back when I didn’t know much about wine, I [bought the second-cheapest wine] all the time!” writes Kirsten Vicenza from Veneto, Italy. “I can confirm that restaurants will occasionally reprice a wine that they need to move to make it the second-cheapest spot on the menu. It sells!”

“Every beverage manager worth their salt knows” about it, adds Kyle from San Francisco, a former wine industry professional.

Knowing this, some readers now purposefully avoid the second-cheapest option. “I used to often order the second-cheapest bottle of wine,” writes Ellen from Brooklyn. “Then I read that because so many people use this strategy, restaurants and bars usually give the highest mark-up to the second-cheapest bottle. Now I order the cheapest and feel smug.” Magazines and other publications have printed similar warnings, too.

But before you avoid the second-cheapest bottles, you should know this kind of price manipulation seems to be uncommon. Mainly because this phenomenon is so subtle that many industry insiders don’t notice it. Or they reject the whole notion.

George Barton of Synergy Restaurant Consultants previously worked as vice president of Beverage and Bar Innovation at TGI Friday’s. We called Barton, and since Barton had access to sales data from a large restaurant chain, we expected it to show the second-cheapest bottles selling quickly, which would inform how the company priced and developed menus. Not so. Barton does not agree with the idea that diners order that way. In choosing wines, his team tended to look at which wines had name recognition and were selling well nationwide. (They also opened and sampled bottles on occasion.) He didn’t strategize about the second-cheapest option. Given that a majority of respondents in our poll pick wine on the basis of other approaches (such as name recognition or server recommendations), it makes sense that professionals may not worry much about which wine they list as second cheapest.

Speaking about the second-cheapest wine is complicated, too, since restaurants and bars can differ drastically from one another. “I’ve heard of it,” says Paul Einbund, who owns The Morris Restaurant in San Francisco. “But in my experience, it’s a myth at sommelier-driven restaurants.” Einbund is a celebrated sommelier who assembled his 60-odd pages wine list after traveling for five years and picking out favorites. At restaurants like his, diners often come specifically for recommendations, and price no longer dictates which wines sell best. Einbund even advises choosing the budget option at upscale restaurants. “At a high-end restaurant, you just don’t sell the low-end wines,” he says. “So whenever I list a very affordable wine, it’s because that wine really blew me away!”

In response to our article, Sam from Colorado pointed out that ordering the second-cheapest wine is an example of a common principle: People usually pick the middle option. This tendency is so strong that companies will offer a third option just so a non-free version feels more like a reasonable compromise. (Think of Pandora Radio, which offers Pandora Free, Plus, or Premium.)

“If there is no sommelier, I do order the second cheapest, and I know what is happening,” writes Sam, of choosing the middle option. “But as long as the second-cheapest wine is still a good wine, what’s the harm?”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook