In the Yellowstone National Park Zone of Death, You Might Legally Get Away With Murder

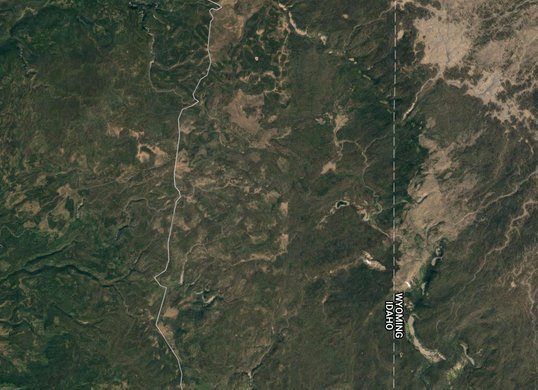

A 50-square-mile patch of Yellowstone National Park in Idaho might just be the perfect place to commit a crime, thanks to a legal loophole.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Dylan Thuras: Yellowstone National Park is this wild, rugged place. It’s got huge, beautiful mountains, lush forests. It’s got wildlife. There are bears and bison just roaming free. So when you hear that there is an area of the park known as the Zone of Death, you might think it means it’s a place where you could fall off a cliff or get eaten by bears. I don’t know, maybe have some kind of Bermuda Triangle navigation issue and just disappear off the map. But here’s the thing: What you actually have to worry about in the Zone of Death is someone murdering you and getting away with it.

I’m Dylan Thuras, and this is Atlas Obscura. A celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. And today, we are taking you to a 50 square mile patch of Yellowstone in Idaho that is perhaps the perfect place to commit the perfect crime. We are going inside the park and outside the law.

This is an edited transcript of the Atlas Obscura Podcast: a celebration of the world’s strange, incredible, and wondrous places. Find the show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Brian Kalt: When I was a little kid, we took a trip there to Yellowstone. And I have a very vague recollection of Old Faithful.

Dylan: This is Brian Kalt. These days, he is a law professor at Michigan State.

Brian: I was pretty young at the time, so I don’t know if I actually remember it or if I just remember remembering it.

Dylan: Back when Brian was a kid, Yellowstone obviously didn’t make much of an impression on him. But little did he know, the park would become a big part of his life. Fast forward to 2003, when Brian was engaged in the endless quest facing all academics: trying to get tenure.

Brian: I was working on an article that I didn’t think I was going to be able to finish before my wife gave birth to our first child. And I didn’t have tenure, so I needed to write something every year. I needed to get something out.

Dylan: Brian needed something that he could write quickly. And while researching, this little footnote popped up about a strange legal gray area surrounding a small section of Yellowstone National Park inside the state of Idaho. The section was just 50 square miles, roughly the size of San Francisco.

Brian: The Idaho portion of Yellowstone is in a remote corner of the park. It’s cut off from the rest of the park, so if you want to drive into it, you have to go hours around. And it’s not visited by that many people.

Dylan: But what was interesting to Brian wasn’t necessarily how remote the area was. It was how it was organized legally.

Brian: This district in Yellowstone crosses state lines.

Dylan: To me, it sounds normal enough. I don’t know, I guess. Seems fine. But to Brian, this presented a kind of legal catnip. So he started digging and digging.

Brian: So the more I hacked away at it, the more I realized that there was something worth fixing.

Dylan: Brian had identified a very curious and potentially deadly loophole. Basically, it looked to Brian like if a person committed a crime in this particular area of Idaho, even murder, they could potentially get away with it scot-free. Okay, let’s discuss the loophole. And to understand how this really works, we have to start with the Sixth Amendment. At which point I was like, oh, yeah, the Sixth Amendment. That’s the one …? Okay, so the Sixth Amendment basically guarantees the right to a speedy trial. That’s the part you may remember from high school civics class. But it also says something else.

Brian: So the Sixth Amendment says that in a federal criminal case, the jury has to be from the state and district where the crime was committed.

Dylan: The jury has to be from the state and district where the crime was committed. State is simple enough, we all know what those are. But districts are a little more specialized.

Brian: The country is divided into 94 judicial districts. Most states only have one district. Like, South Carolina is just the District of South Carolina. Some of them are divided into two or three or four. I’m in the Western District of Michigan right now.

Dylan: None of these districts cross state lines, except for one: the District of Wyoming, which includes the entire state of Wyoming, plus the portions of Idaho and Montana that fall within the boundaries of Yellowstone National Park. And the reason why this happened, the reason this is the only district in the U.S. that crosses state lines, is mostly the result of a historical accident.

Brian: It goes back to the formation of Yellowstone, which became a national park before Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana became states. And because they had this federal area out there, they had issues with there not being any law.

Dylan: Eventually, the whole of Yellowstone was just looped under Wyoming state criminal codes. Probably, you know, just to keep things simple. But as Brian was realizing, it created a big legal problem.

Brian: So, that means if you commit a crime in the Idaho portion of Yellowstone, the jury has to be from the state, Idaho, and the district, District of Wyoming. And the only way you could do that would be if the jurors were from the Idaho portion of Yellowstone. But nobody lives there. Well, nobody will live there. It’s a remote part of the park. You can’t just build a house there. So, there’s no way for the federal prosecutors to prosecute you while giving you a jury that the Sixth Amendment entitles you to.

Dylan: Brian is quick to point out this is not a free for all. There are limitations. Say, for example, you committed a crime in the Yellowstone Zone of Death, but you had planned it at home. Well, you could still be charged for conspiracy in the state you had planned it in. Things like that. But say it was a crime of passion, something spontaneous. Say I’ve invited you hiking and it’s just the two of us and it’s a long remote hike and we get to talking. And I find that you’ve been spending a lot of time with my wife. You got dinner together. You went roller skating. You got those long straws and you shared a milkshake and—just come over here and shove! Down you go. And thanks to this strange legal loophole, I might just walk away scot-free. And you, my friend, would have entered the Zone of Death. Once Brian realized that there was actually a there there, his relief that he had something to write about quickly turned to worry.

Brian: I was concerned that if I published this, it would be providing an instruction manual. I don’t want anyone to get away with a crime. I wanted it to be fixed.

Dylan: The Georgetown Law Review accepted the article and Brian asked if they could delay publication to see if he could get Congress to, you know, fix the loophole.

Brian: Congress colored outside the lines here, and they could fix this easily. They just need to redraw the district lines, which is just a simple statutory fix to make the District of Wyoming like every other district and have it follow the state lines. I mean, I wrote a statute that would fix it. It’s four lines long. It literally would take them five minutes.

Dylan: So Brian started writing. He wrote letters to members of Congress and their staffs. He wrote to the Department of Justice, to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Wyoming. And in return, he got nothing.

Brian: Like if I wrote to McDonald’s and I said, hey, the Sixth Amendment, Yellowstone, all that, they would write back and they’d say, thank you for writing to us. Here’s a coupon for a Big Mac. They wouldn’t do anything about it, but at least they would acknowledge my existence. But they didn’t respond at all.

Dylan: In 2005, Brian’s article came out. They could only delay it for so long. And soon enough, his theory was actually put to the test. In 2005, a guy named Mike Belderane was out hunting around the Montana border of the park. And he spotted and shot an elk, which he then dragged back to his truck, which was parked inside of Yellowstone. So, OK, no one was pushed off a cliff. But poaching in Yellowstone is still quite a serious crime.

Brian: The guy poached an elk and he didn’t know about my law review article when he did it. But his lawyer did and they raised the argument.

Dylan: Belderane’s lawyer argued that since the crime had taken place in Montana, his client could not be tried in Wyoming. And the Montana portion is still pretty sparsely populated. So it would have been tough to put together a jury there anyway.

Brian: And the judge wrote an opinion that said basically, yeah, that’s what the Sixth Amendment says, but I can’t just let you go. I can’t create a no man’s land here.

Dylan: Next, Belderane could have appealed the issue to a higher court, which in this case would have been the Tenth Circuit. Instead, the prosecution offered him a plea deal, basically a lighter sentence. But as part of it, he could not push this loophole issue any further. Belderane accepted and was later sentenced to four years in prison.

Brian: They got their conviction and they can point to that and they can say it’s a myth that you can get away with anything in this Zone of Death because this guy didn’t. On the other hand, what they telegraphed was that they were afraid of what the Tenth Circuit might do with this case. And because the district court didn’t really offer any explanation here, the loophole still looms. And they could have settled it in that case, which was just about an elk. But now, you know, someone with nothing to lose, someone who commits a murder might be able to get away with it.

Dylan: Today, almost 20 years after his article was published, Brian still keeps tabs on the Zone of Death.

Brian: Most recently, the Idaho legislature passed a resolution asking Congress to fix this. But to my knowledge, Congress has not paid any attention to that either. My son was born in 2004. He’s a freshman in college now and they still haven’t closed the loophole.

Dylan: But while Congress ignores the Zone of Death and does whatever it does, in the meantime, Brian’s theory has taken off elsewhere.

Brian: The TV series Yellowstone, some people have suggested that this notion of taking someone to the train station that they use on the show is loosely based on my theory. They’ve never gone into that much detail about it, so I don’t know.

Dylan: The crime novelist C.J. Box was even inspired by Brian’s article to set a murder mystery in the Zone of Death. It became his 2007 book, Free Fire, and Box actually invited Brian to come out with him to do a couple of events in Yellowstone.

Brian: They flew me out there so that I could answer the technical legal questions about it, and I really enjoyed it, it’s a great park. But at one point someone said, hey, maybe we could drive down to the Idaho portion and, you know, take some pictures there. And I said, hell no. I know how irony works. I’m not setting foot in there until and unless they fix this. I’m happy to go to Yellowstone anytime I can, but I’m not tempting fate by going to the Idaho portion.

Dylan: You can visit the Yellowstone Zone of Death if you dare. It’s actually a very beautiful scenic section of the park filled with lots of beautiful forests and stunning rivers. Just don’t expect Brian to come with you and be very, very careful about who you invite. A huge thanks to Brian Kalt for telling us all about the Yellowstone Zone of Death.

Listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and all major podcast apps.

Our podcast is a co-production of Atlas Obscura and Stitcher Studios. This episode was produced by Amanda McGowan. The production team includes Doug Baldinger, Chris Naka, Kameel Stanley, Manolo Morales, Baudelaire, Gabby Gladney, Gianna Palmer. Our technical director is Casey Holford.

This episode was sound designed and mixed by Luz Fleming. If you want to learn more, be sure to visit atlasobscura.com. There’s a link in our episode description. Our theme and end credit music is by Sam Tindall.

And I’m Dylan Thuras, wishing you all the wonder in the world. I’ll see you next time.

This story originally ran in 2023; it has been updated for 2025.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook