Fun and Games With The World’s Oldest Deck of Cards

The smart phone sort of gives away the time period here. (All photos by Eric Grundhauser unless otherwise noted)

What did people in the 15th century do for fun? It was not known as a real “party” era, as France and England continued the bloody Hundred Years War, Joan of Arc was burned at the stake and the Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople and ended the Roman Empire in a seven-week siege. Oh, and Spain began its inquisition. But one relic of happier times has survived: the world’s oldest completed deck of playing cards.

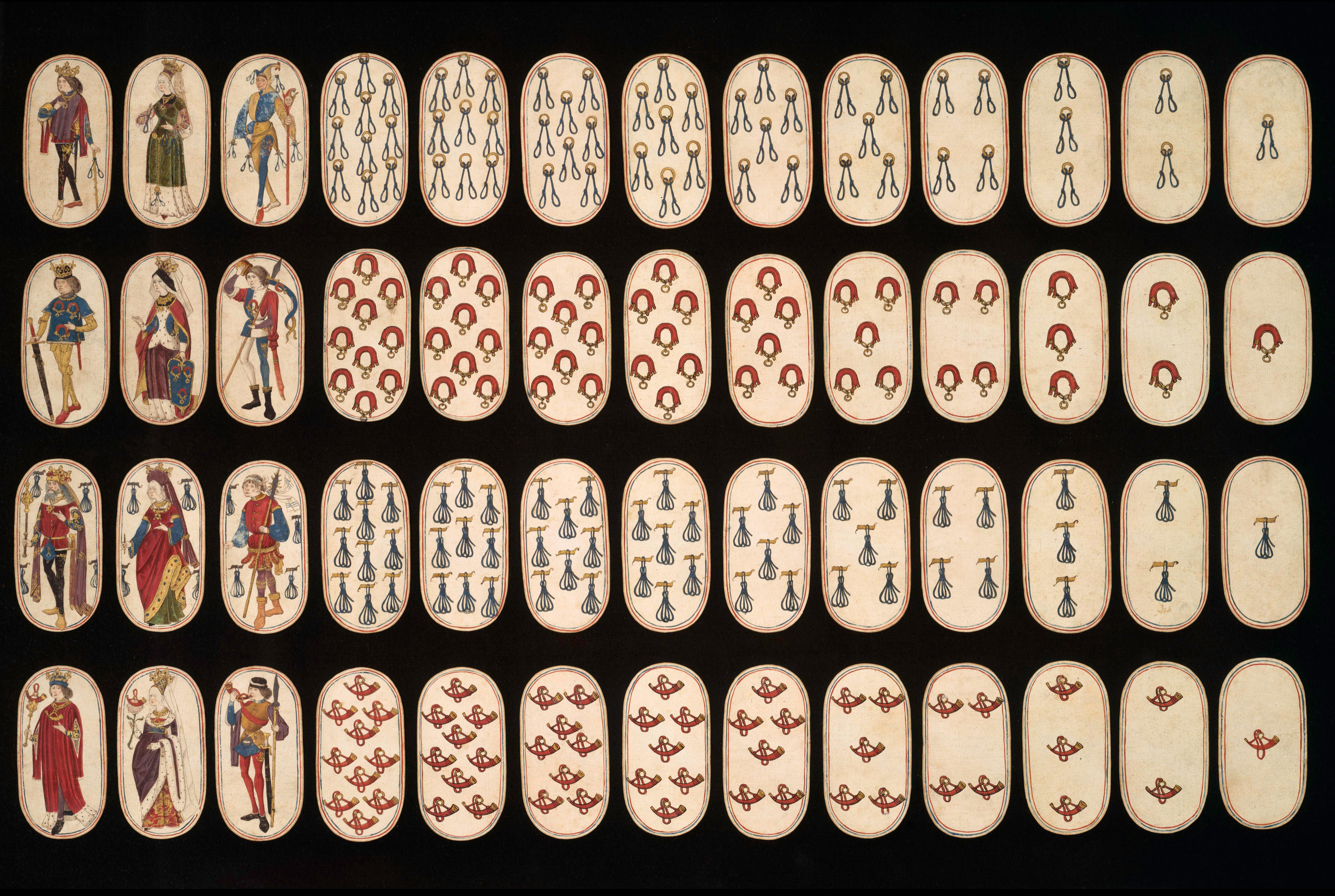

Known alternately as the Flemish Hunting Deck, the Hofjager Hunting Pack, or the Cloisters Pack (it is held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cloisters location), the set of cards now recognized as the oldest in the world was originally thought to be just kinda-historic. The oblong cards are made of pressed layers of paper decorated with stenciled and hand-drawn designs, and overlaid with silver and gold. The art on the cards is clearly medieval in origin, but the completeness of the deck, the resemblance to modern card design, and the nearly pristine condition had many appraisers questioning the actual age of the pack.

The Hofjager Hunting Pack (Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Met acquired the deck from an Amsterdam antiques dealer in 1983. It was once believed that the cards dated back to the 16th century, but the dealer thought they were even older, and purchased the whole set for a mere $2,800. After investigating the cards in detail (the dress of the Burgundian royal figures painted on the face cards, and a pair of watermarks found elsewhere in the deck), it came out that they were actually created between 1475 and 1480 CE.

Although now more than 500 years old, the game resembles a contemporary 52-card deck to a surprising degree. It’s certainly fun to look at, but we wondered: what would it be like to play a 15th-century card game?

According to playing card scholar David Parlett’s book, A History of Card Games, it was during the early 15th century that mass-produced decks of cards first became a going concern. The main centers of playing card production were in Germany and France, although the trend soon carried across most of Europe.

Unlike the standard decks we know today, with their uniform quartet of 13-card suites, the decks produced in the early 1400s took on variations depending on the regions they came from. Some packs would contain a fifth suite (which may have been a back-up), or the courtly face cards would have an extra rank, but the symbols used in the suites themselves were all over the place. Suitmarks ranged from birds to acorns to cups to helmets to flowers depending on the origin of the deck.

Such is the case with the Cloisters Deck, the theme of which seems to be falconry. The four suites consist of hunting horns, dog collars, hound tethers, and game nooses, which stand in for the modern day hearts, clubs, diamonds, and spades. However beyond these symbolic differences, the deck is remarkably similar to a pack of cards you might see on the tables of Vegas. Each suite still contains 13 cards, and the court cards are all recognizable as the King, Queen, and Jack (or Knave, in the case of the Cloisters Pack). For all intents and purposes, one could still use this deck to play a round of Hold ‘Em.

Of course, poker didn’t exist in the 15th century, so what were people doing with these cards? Given the pristine nature of the Cloisters Deck, it’s likely that it was never used for playing in a pub, but was instead a collector’s curiosity. We once again turned to David Parlett for answers:

“It’s hard to specify what games were played where in 15th-century Europe. We have a number of references to various names of games, but they are not all identifiable for certain, as books of rules were not published till the 17th century. The earliest known trick-taking game is Karnöffel […]. Gambling games would have included (at least in Germany) Bocken, the ancestor of Poker; perhaps Thirty-One, the ancestor of Blackjack; and the ancestors of what we now regard as simple games for children, such as Beggar-my-Neighbour. The French game of Triomphe, ultimate ancestor of Whist and Bridge, may possibly have been developing at this time.”

So while we can’t be certain of the exact games the Cloisters Deck might have been destined for, we still wanted to answer the question: was the deck any fun?

Is this a good hand? I have no idea.

Is this a good hand? I have no idea.

The museum would not let us play with the deck itself (full disclosure: it seemed silly to ask), so with the magic of glue and a color printer, we made our own Hofjager Hunting Pack and gathered Atlas Obscura staffers together to attempt to play the oldest card game we could find rules for, Karnöffel.

First recorded in Bavaria in 1426, Karnöffel is a game that seems like it must be one of poker’s ancestors. Essentially, players are given a hand of five cards, and then play each card against their opponents, trying to bluff and raise the point value with each trick. The specific rules can be found here.

The hardest part of the game to our modern minds was the hierarchy of trump cards. It follows a logic that is only barely based on the actual card numbers. As staff writer Sarah Laskow explains:

“The best/most confusing part of the old game was the relative strength of the cards. The devil beat 6, which stood for the pope. But 6 beat the king. And 3 was more powerful than 8 for some reason.”

This likely made sense to seasoned players at the time, but to two Internet writers, it was a bit baffling.

Nonetheless, we made our way through three hands of the game, and by the end of the third we had a pretty good handle on the archaic mechanics. And frankly it was getting pretty fun.

You’ve just activated my trap card!

You’ve just activated my trap card!

It seems that betting, bluffing, and getting the upper hand on your opponent is just as satisfying today as it was in the 1400s.

The Hofjager Hunting Pack can currently be viewed at the Cloisters in Manhattan.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook