The Mexican Revolutionary Who Fought for Freedom on the Battlefield and in the Barroom

Before she became a spy, Petra Herrera went undercover as a man.

For Women’s History Month, Atlas Obscura delves into the world of espionage, where being overlooked and underestimated has been an asset for centuries of women spies. Read about more of history’s hidden Secret Agent Women.

Pedro Herrera awoke each morning before dawn in a military camp in northern Mexico to dress and shave a beard that was “just starting to grow out,” as Herrera reportedly told the other soldiers. The 20-something was a respected figure in the revolutionary unit, a natural leader with a skill for blowing up bridges and an unquestioned reputation for fearlessness. Herrera was also deep undercover.

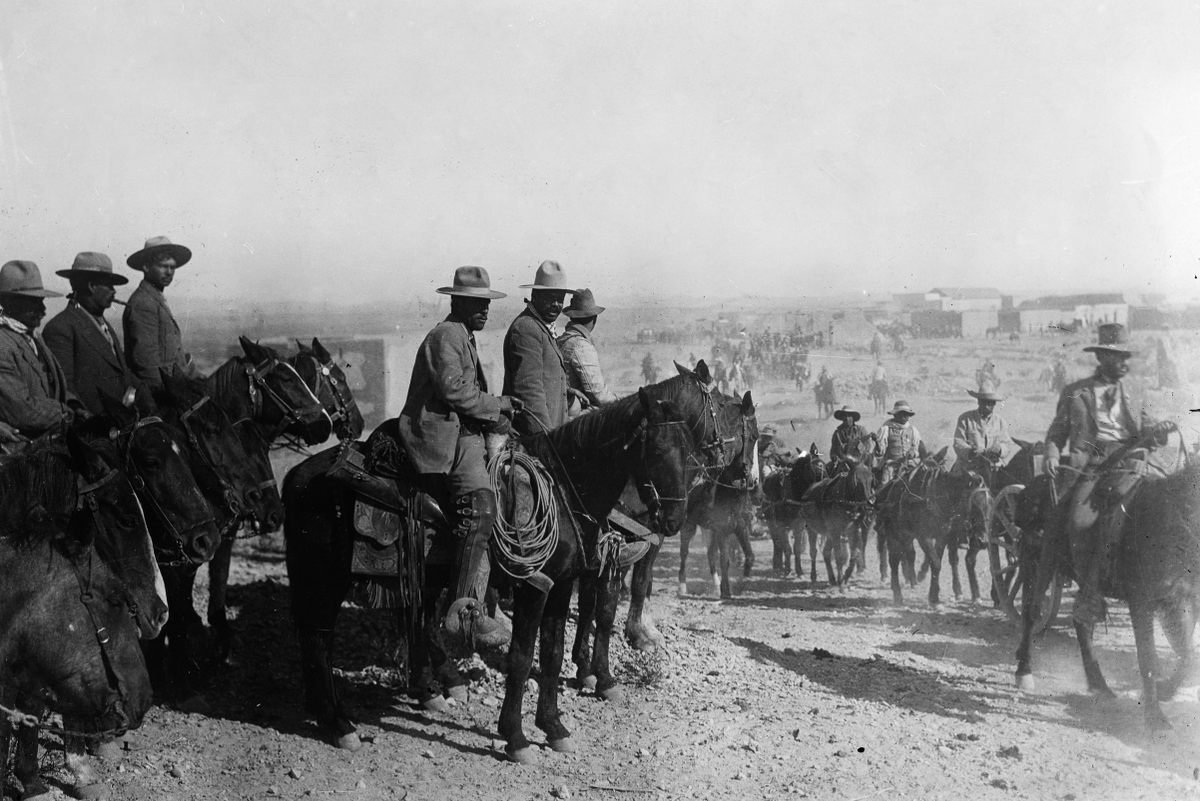

Pedro Herrera’s real name was Petra Herrera, and she had infiltrated Pancho Villa’s División del Norte in 1913 in disguise. But she was not a spy—not yet—she was just a woman who wanted to fight with a rebel army reluctant to welcome female soldiers in its ranks.

Little is known about Herrera’s life before she joined the fight, but she was unwilling to remain anonymous as the Mexican Revolution wore on. Once she had been accepted by the men, she revealed her secret, unfurling long braids that would become her trademark, and reportedly shouting out her identity: “I am a woman.”

As she must have hoped, Herrera’s revelation did not change things, at least at first. In January 1914, the Mexican Herald reported, “Rebel leaders here were pleased to receive the first report from Peda [sic] Herrera, a young Mexican woman who is commanding a force of 200 men in the state of Durango. She holds the rank of captain in the rebel army.” Herrera was also part of Villa’s force in the Second Battle of Torreón in the spring of that year—at least according to oral history. Her name does not appear in the official records of the fight, but another soldier reported Herrera “was the one who took Torreón.” Corridos were written about her exploits: “The valiant Petra Herrera / To battle she entered / Always being the first / To start the exchange of fire.” The last stanza of the ballad proclaims, “Long live Petra Herrera.”

And Herrera was not alone. There were an estimated 400 women who participated in the Second Battle of Torreón. “Perhaps Villa was unwilling to let it be known that women played such an important part in the battle,” writes Elizabeth Salas in Soldaderas in the Mexican Military. “It is possible that lack of acknowledgment and failure to be promoted to a generalship motivated Herrera to form an independent brigade of female soldiers.” Estimates of the size of her unit ranged wildly, from 25 to 1,000, and may have varied with the conditions of the war. Through it all, Herrera’s fame only grew.

But none of it was enough to earn her the title of general. Around 1917, when fighting lessened, Herrera—who now pledged her allegiance to Venustiano Carranza, once an ally of Villa’s but by then an opponent, and who would become the country’s new president in 1917—was made colonel before she and the rest of her female soldiers were dismissed, “because it was an army of women,” one observer said.

So Herrera went undercover again. This time she served as a spy for the same Carrancistas who had disbanded her unit. The wartime leader was playing the role of a nondescript waitress at a cantina in Jiménez; Chihuahua had long been a Villa stronghold and Herrera’s former ally still held sway among some there. From her place behind the bar, Herrera quietly collected intelligence.

Some time later—the exact date is not recorded—Herrera was confronted by a group of men in the bar. Had someone recognized her long braids and remembered her acts on the battlefield and her shifting loyalties? No one knows what caused one of the men to produce a pistol and shoot her three times. The doctor who fought to save her life believed they had a vendetta against her and would return to kill her if she survived. But Herrera died of her wounds. Her doctor blamed her passing on both an infection and—quite inexplicably, given Herrera’s years of brave service—a fear of her attackers.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook