The Mandatory Canteens of Communist China

They led to one of the worst famines in history.

In 1958, Chinese communist cadre descended into farmers’ homes on an official government mission: to confiscate food supplies and cooking equipment, and destroy private kitchens. Officially, the communist government demonized private kitchens as “symbols of selfishness.” But for Chinese farmers, this meant that the ubiquity of cooking and eating meals at home suddenly became illegal.

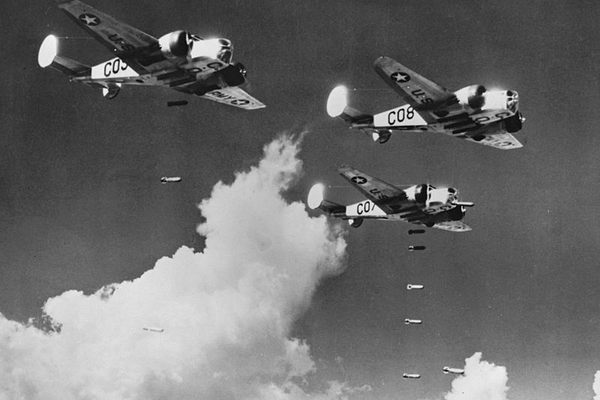

The measure stemmed from Chairman Mao Zedong’s “Great Leap Forward,” a series of communist government initiatives that revolutionized the Chinese countryside. Mao believed that agricultural collectivization was central to building a new socialist consciousness in China, and thought of rural society as critically important to furthering that goal. The People’s Commune, a system that consolidated farmers into communes averaging 23,000 members, also became pivotal to this ethos.

Besides abolishing private property and dividing work among households, these communes centered around communal canteens (Gonggong Shitang), a free dining system designed to feed commune members. Communal dining didn’t last all that long, and was eliminated in 1962. But contemporary academics believe it played a major role in causing one of the worst famines in human history, killing an estimated 30 million people.

Officially introduced in August 1958, the communes cropped up swiftly. By October 1958, 99.1% of all farmers were placed into communes containing 2.65 million canteens. Canteens varied in size (some could serve 1000 people during meal times) and were constructed from confiscated tables, utensils, and kitchen equipment. A ringing bell signified the start of meal times, prompting farmers to line up single file to be served cafeteria-style rice or wheat buns, soup, and vegetables before sitting down to eat in a central dining area.

Although food was free, there was no other choice. Dining was restricted to canteens, and all private kitchens and food supplies were banned. Still, most Chinese farmers kept private stockpiles of rice along with preserved foods to supplement fresh vegetables. But fearing confiscation, many farmers ate these stockpiles before the collectors came. And with all food grown by the farms sent directly to canteens, the entire food supply became monopolized into the canteen system.

In the beginning, the canteens were treated like a miracle. A popular slogan invited diners to “open your stomach, eat as much as you wish, and work hard for socialism.” Farmers reveled in this new system and gorged themselves. Some farmers even ate when they weren’t hungry. Author Han Suyin, who wrote an autobiography spanning her experiences in early Communist China, observed farmers stuffing “themselves with vast amounts of pork flesh, each peasant eating and carousing, ‘Why save? The government will provide. This is communism.’” This cavalier attitude meant that leftovers were thrown away, resulting in massive amounts of food waste.

Problems arose almost immediately, and signs of famine appeared as early as the winter of 1958. Historically, Chinese farmers maintained food stockpiles to prepare for shortages or slow harvest years. In some of the new canteens, farmers ate through a six-month supply of rice in 20 days. According to professors Gene Hsin Chang and Guanzhong James Wen, two historical experts on the famine, overconsumption and the canteens’ monopoly on food became major catalysts for the famine. When famine conditions encroached, farmers had no access to their traditional supplies of food and were hostage to the dwindling food supply of the canteens.

By spring 1959, the famine had metastasized beyond control and resulted in extreme misery. The carefree days of feasting quickly morphed into hunger. Accounts from famine survivors paint a grim picture. Famine survivor Lao Tian describes canteen meals during the famine as consisting of “a bun or two with a bowl of water. At most we got to eat 500 grams of food a day…The buns were made of a mixture of corn and bark. Only very occasionally we got buns made of corn only.” According to other accounts, average food amounts for farm laborers were as low as 150 to 200 grams of food per meal. Rice, a staple of the Chinese diet, was unavailable. Instead, meals during the famine included the likes of watery wheat porridge, sweet potatoes, sweet potato leaves, carrot leaves, and hemp noodles, which were made by cutting “the roots of the plant into long silvers.” Farmers also ate the bark from parasol and loquat trees.

Massive corruption further exacerbated the problem. Corrupt cadre took advantage of their status to eat as much as they wanted from the canteens and often reported inflated agricultural production numbers. It didn’t help that farmers had little incentive to work, since everyone received the same food. They still had immense production goals at the time, which many farmers found impossible to fulfill.

To combat the outsized production goals, inventive farmers created a method called “roadside farming” to fool government inspection teams. This method involved planting crops only on the fields closest to the roads and leaving the remaining fields outside of view deserted, which then mislead government inspectors. Despite these deceptions, by the end of 1960, the rising death toll and drastic food shortages forced the government to acknowledge that the canteen system had failed. After a series of debates with high-ranking officials, Mao finally relented. All communal canteens were eliminated two years later.

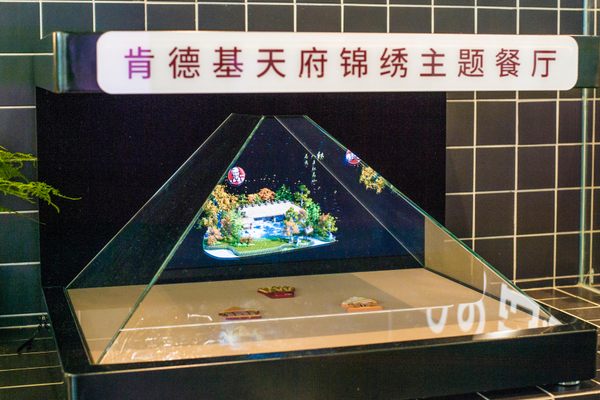

Despite the canteen system’s disastrous consequences, restaurants that harken back to Mao’s China have emerged in cities such as Beijing and Chongqing. These spaces, with staff donning time-appropriate communist suits, use gimmicks to project nostalgia about a simpler time, and a China that no longer exists. These modern restaurants, with their abundance of food, may have been close to what Mao originally imagined for his communal canteens. Only now it exists is in ultra-capitalist, modern China, an ironic twist of fate for the canteen of the People’s Commune.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook