The Staggering Scope of the Plastic Threat to Coral Reefs

Garbage floating in the ocean is likely to be swarming with bacteria, which can make corals sick.

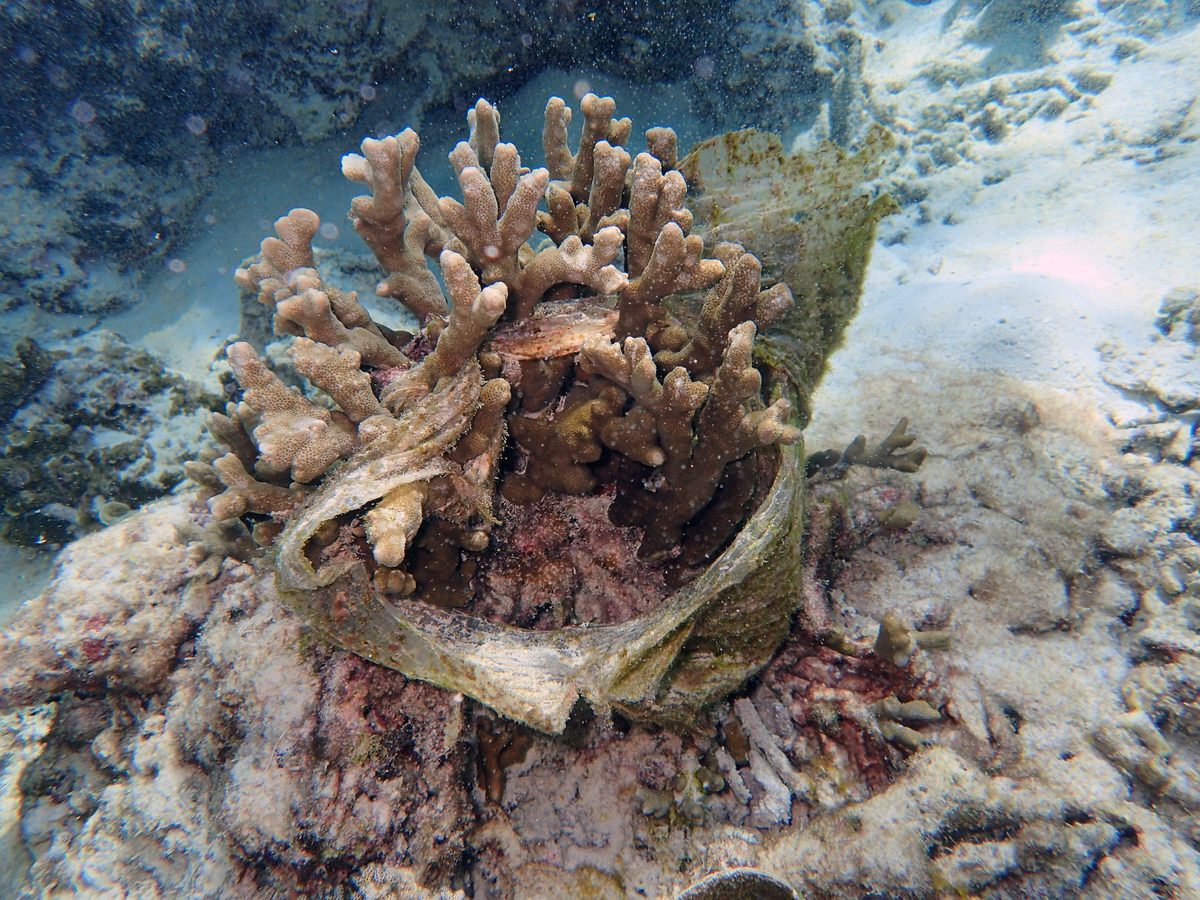

Dancing in an ocean current, a single scrap of plastic doesn’t appear especially insidious. Toothless, tailless, twirling, it might look, at first, more evanescent than threatening. But snared on corals or heaped in piles, plastic waste poses deadly risks to vast underwater ecosystems.

It’s not news that oceans and shores are pocked with trash, or that reefs are in dire straits. Microfibers sloughed off textiles, packaging, and more have washed ashore in multi-colored waves, and been found in the stomachs of creatures roaming trenches miles below the surface. The staggering scope and steep risk of this accumulation, though, has been freshly quantified in a new study published today in Science. Corals have been ailing for some time, and plastics are making them sicker.

Led by Joleah Lamb, a postdoctoral research fellow at Cornell University, researchers surveyed 159 reefs near Indonesia, Australia, Myanmar, and Thailand—a band where more than half of the globe’s reefs are clustered. To assess the relationship between debris and and disease, the scientists tabulated the trash entangled on the corals and kept a lookout for telltale indicators of ill health, such as white bands, lesions, or tissue loss.

Since plastics can effectively shrink-wrap colonies, choking out light and oxygen, they introduce stress that leaves coral vulnerable to disease. To make things worse, the garbage is likely to be swarming with bacteria. “Plastics make ideal vessels for colonizing microscopic organisms that could trigger disease if they come into contact with corals,” Lamb said in a statement. Items made from polypropylene, in particular, are often teeming with pathogens. Microbes are thought to be partly culpable for maladies such as white syndromes, which denude and devastate reefs. Of the corals studded with plastic, Lamb and her team found that 89 percent were suffering from disease. When plastic was absent, the disease-addled share was closer to 4 percent.*

Trash talk aside, reefs already have a lot stacked against them. In a recent study of more than 100 reefs, another group of researchers found that bursts of especially warm water were causing spikes in coral bleaching, which leads to toxicity and rot. It’s possible for reefs to bounce back from these brushes with bleaching, but they have less and less time to do so. Reefs typically need at least 10 years to recover from severe bleaching, but they’re now get walloped about every five years.

“It’s like getting hit by a serious disease every couple of years, or at such short intervals that you don’t have time to recover in between,” Julia Baum, a marine biologist at the University of Victoria, told National Geographic. Discussing the new Science paper, Lamb likened the progression of white syndrome to a case of gangrene that rages and spreads, uncontrollable.

Reefs are home to roughly a quarter of marine life, and anchor many local economies. Because they buffer shorelines, reefs also help mitigate storm surges that can swamp coastal communities. Healthy reefs function as submerged breakwaters, “reducing and dissipating that wave energy offshore, so that then only tiny little amounts of wave energy come onshore,” Michael Beck, lead marine scientist at the Nature Conservancy, explained to the Washington Post. Since sick corals are brittle and liable to be fractured by waves, they’re worse at this job.

Lamb and her collaborators detected plastic on a third of the reefs they studied, estimating the total number of pieces to be around 11.1 billion. By 2025, they expect the number of plastic castoffs lodged in reefs to tick up by 40 percent, to a total of 15.7 billion.

The prognosis could inspire a frank discussion—and maybe a suite of laws—around offloading this debris, explained Drew Harvell, a coauthor and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Cornell. “Our goal is to focus less on measuring things dying and more on finding solutions,” Harvell said. But understanding the ugly afterlife of a shredded bag or plastic bottle is a good place to start.

*Update 1/26: This story has been updated to include details about the percentage of corals suffering from plastic-related diseases.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook