New Orleans Has Been Using the Same Technology to Drain the City Since the 1910s

The Wood screw pumps are mechanical marvels, but the turbines that power them are another story.

More than 100 years ago, New Orleans was on the forefront of urban infrastructure.

Since its founding in 1718, between the natural levee of Mississippi River banks and higher land along the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, the bowl-like city has never had adequate drainage. In its early days, New Orleans’s system of drainage ditches and canals “was totally inadequate, even for a town with as little runoff as early New Orleans,” according to a 1999 Army Corps of Engineers report on the city’s drainage history. During storms, each of the city’s blocks became an island surrounded by flood waters. One year, Mardi Gras parades waded through flooded streets. The soggy city was a breeding ground for mosquitoes and the diseases they carry.

In the 1890s, the city council decided to deal with the “extraordinary disastrous condition” of the city’s drainage. By the turn of the century, the city had built giant drainage canals (today mostly hidden underneath the streets, so big that a truck could drive through them).

But moving water out required pumps to get it up and over the higher land rimming the city. The canals carried water from pumping station to pumping station, until the end of the line, where it was pumped into Lake Borgne or, if necessary, Lake Pontchartrain. There were pumps built into the original drainage system, but in the 1910s, a local engineer, Albert Baldwin Wood, built New Orleans better pumps than any city had ever had.

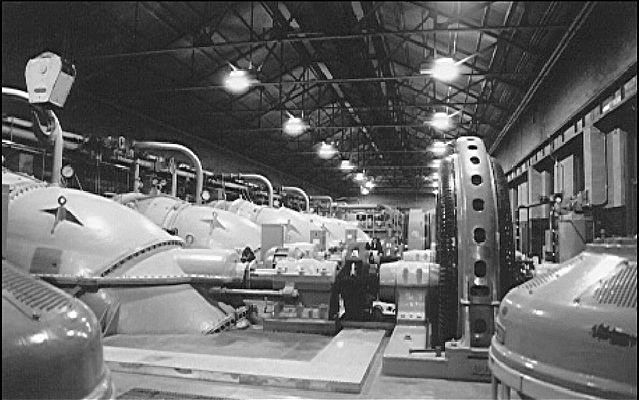

“For their time, they were a real mechanical marvel. The real backbone of the current system is these historic pumps, and they work extremely well,” says Benjamin Maygarden, a historian and lead author of the Army Corps report. One early Wood pump is still working as a constant duty pump—for day-to-day drainage, rather than pulses of storm water—at Drainage Pumping Station No. 1, says Maygarden, who’s now a project manager at Gaea Consultants in the city. “It’s still in almost daily use. They’re really remarkable mechanical things.”

Wood’s innovative pumping system made it possible for New Orleans to thrive and expand, despite the city’s less-than-ideal location. A century after their creation, his pumps are still engineering wonders. But they come with a caveat. Many of the pumps use an outdated electrical standard, and the city generates power just for them, with turbines that are difficult and costly to maintain. They’re unreliable enough that this past summer a rainstorm caused the city to flood for days, and whenever hurricanes threaten—like Tropical Storm Nate, which is heading through the Gulf of Mexico this weekend—the system’s weak spots are put to the test.

Albert Baldwin Wood was a New Orleans native, so dedicated to the city that he rarely left, even after other cities starting clamoring for his help. He started working for the Drainage Commission in 1899, as Assistant Manager of Drainage, and spent 55 years with the city’s Sewerage and Water Board, which had merged with the commission in 1902.

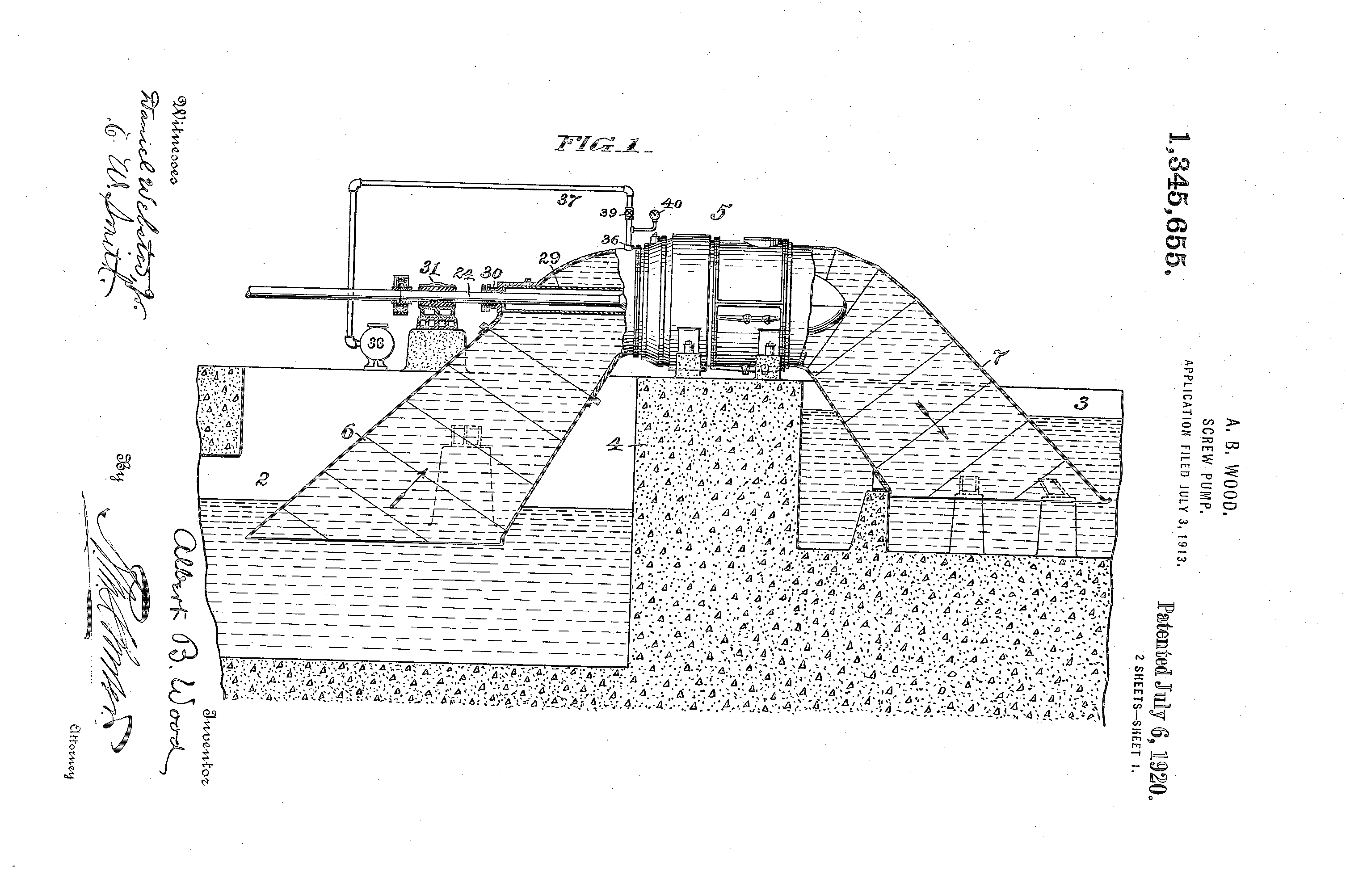

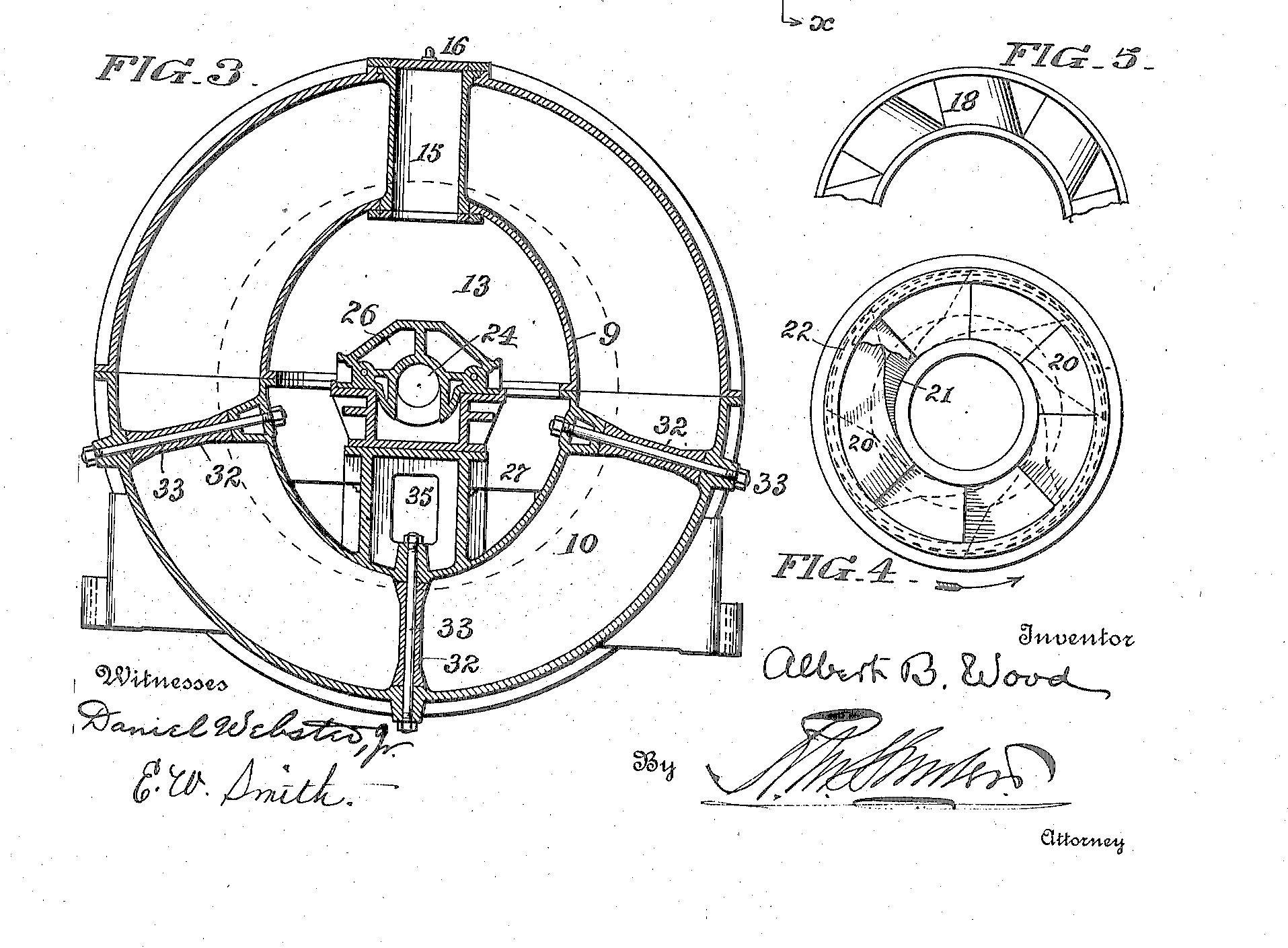

Wood’s original job was to address the city’s overwhelming and increasing drainage needs. He started designing pumps, and by 1915 had created the giant, horizontal screw pumps—the largest and most advanced pumps of their time—that are his legacy.

He had started small, by designing an experimental pump just a foot long. Whereas New Orleans’s prior pumps had been vertical, this one lay on its side. A vacuum pipe sucked the water into the pump’s rotating center and through to the next canal or the lake at the end of the line. Wood scaled the original model up to 30 inches, then 12 feet. One of the genius aspects of Wood’s design is the ease by which the interior could be accessed for maintenance: Hatches on top let people pop inside, and the space was big enough to fit multiple people. The city ordered 13 of them.

In 1915, four of Wood’s 12-foot screw pumps went into action. “Getting the pump castings from the nearest railroad siding to the pumping stations, and then erected, was an engineering feat in itself,” Maygarden and his colleagues wrote in their report. Each pump, on its own, was 100 tons. Most importantly, though, they worked. An independent evaluator from Tulane University wrote, “Emergency service is probably the weak point of the old pumps. It is the forte of the new. Results show that the pumps easily answer all requirements and that they are the largest and most efficient low-lift pumps in the world.”

Wood’s system was so successful that it was replicated all over the world, from the Netherlands to China. The pumps only got larger, too: In 1929, 14-foot pumps started duty, with the aim of doubling New Orleans’s drainage capacity. By then, the original 12-foot pumps had been going for 10 years. In 1924, Wood wrote that the pumps didn’t show “any signs of wear or deterioration.”

That very first 12-inch screw pump is still in New Orleans, in Drainage Pumping Station No. 1. While that small pump is displayed as a relic, Wood’s pumps have been working to keep floods at bay for years. The city today has 120 pumps, and dozens of them are Wood screw pumps.

The electrical system that powers these older pumps, however, is a different matter. Older pumps, installed before the 1970s, run on 25-cycle power, which has long fallen out of use in favor of 60 Hz electricity. To make 25-cycle electricity, New Orleans is still running decades-old steam boiler turbines that require specially trained machinists to maintain them. When the turbines need repairs, the city often has to either order a bespoke part from an outside company or have it made specially, in-house. As the people who know how to keep these turbines running have retired, they’ve been hard to replace, and inadequate staffing has forced employees to work overtime.

The upshot of this is that, of the city’s four 25-cycle generators, one has been under repair since 2012. When they opened it up for refurbishment, “engineers kept finding more parts that need to be fixed and others that had to be built from scratch,” The Times-Picayune reported. This past summer, two more turbines were already offline when a fire shut down electricity in the fourth. In early August, a storm dumped nearly 10 inches of rain on the city and, without enough power, the drainage system couldn’t handle the storm. Neighborhoods flooded, and it took days for the working pumps to dry the city out.

There have been some rumblings about replacing these old turbines. A 2012 report, commissioned by a task force dedicated to reforming the system, recommended that the Sewerage and Water Board stop putting money into the old system, and instead convert to modern 60 Hz power. “The pumps are amazing, volumetrically, at what they can take on,” says Jeffrey Thomas, whose consulting company put together the 2012 report. “The Achilles heel is the power.” The type of flooding experienced in August, he says, was inevitable. Eventually the day would come when heavy rainfall coincided with problems with the pumps’ power supply.

Right now, though, there are no workable long-term plans to change the technology. The Wood pumps were designed in “the age of over-engineering,” says Maygarden, which is why they’re still chugging. Wood and the engineers of his day could not have anticipated the massive amount of runoff, from pavement and rooftops, that the pumps would have to deal with, but they were well-made enough to handle it. Some pieces of urban infrastructure do last hundreds of years. If the Wood pumps are hooked up to a more reliable power source, who knows how long they could last?

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook