New Hampshire Mill Workers Invented A New Type Of French

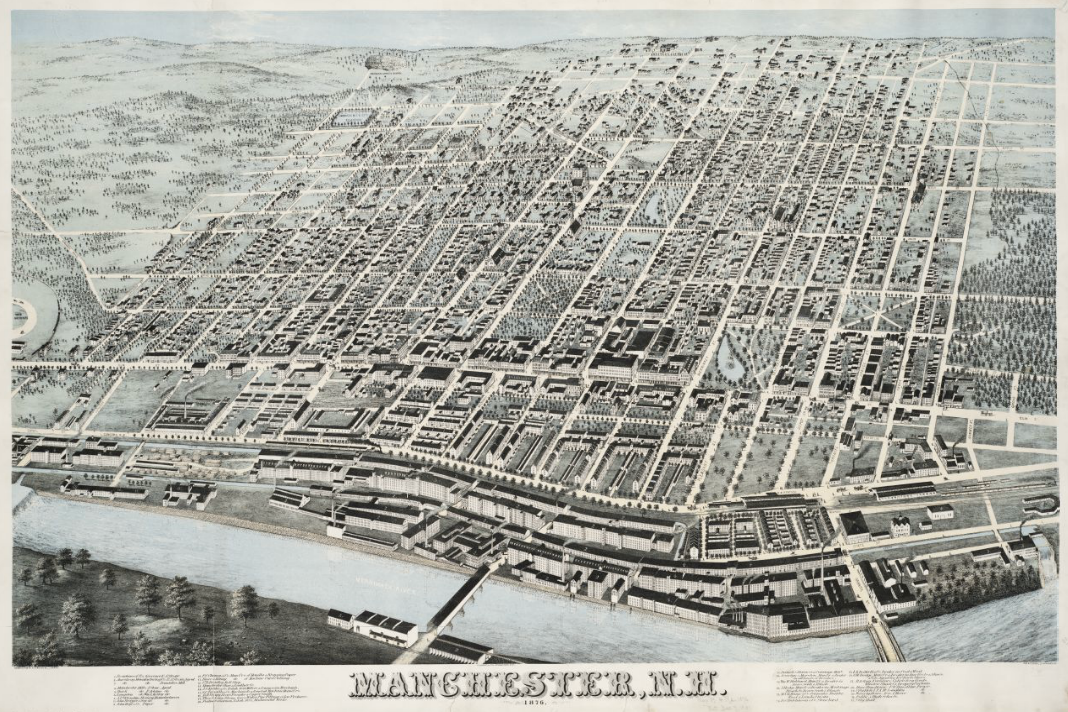

Manchester, 1875 (Image: Boston Public Library/Wikimedia)

Berlin, New Hampshire, is an out of the way sort of place. The paper mill that once drew people there closed about a decade ago, and today the population hovers just above 10,000 people. Though moose roam the woods just outside of city limits, Berlin is still the largest town in Coös County, where the New Hampshire border meets Québec.

What distinguishes the city these days is the unique language that people speak there. Berlin is one of the largest French-speaking communities in the entire country, a surviving cluster of a great migration from Québec into New England. It is also one of the few places where a particularly American variant of French is spoken.

Across New Hampshire, about two to three percent of the population speaks French; these communities are concentrated in mill towns–Berlin in the north, Laconia in the central part of the state, Dover and Rochester toward the eastern seacoast, and Manchester in the south. Between 1840 and 1930, some 900,000 French-Canadians left Québec and came across the border to work in New England. By the early 20th century, Franco-Americans were the largest immigrant group in New Hampshire.

The language and the culture they brought with them survives in pockets, where people speak an English-inflected French dotted with technical loanwords picked up at the mill. Tourtière–a French-Canadian pork pie–makes a ceremonial appearance at Christmas. Few people outside the state, though, realize that New Hampshire has any French connection.

“I think that one thing people are often surprised by is that New Hampshire’s Franco-Americans exist,” says John Tousignant, the executive director of Manchester’s Franco-American Center.

Christmas tortière (Photo: Roland Tanglao/flickr)

More well known (and more numerous) are Maine’s Acadians. Those French-speaking communities, though, have a different history from Franco-Americans in New Hampshire. Acadians had settled in Maine even before the Revolutionary War, and tended to be more oriented towards the sea than the agricultural Quebecois.

The French that Acadians speak is different, too. Instead of the typical first-person verbs of avoir, to have, or etre, to be (j’avais or j’étais in common French), they’ll use a plural–j’avions or j’étions. And their vocabulary is tinged with words of the sea. Quebecois French would call a staircase un escalier. But Acadian French would call a staircase une échelle, which usually designates a ladder, such as those found on a ship.

New Englanders with French heritage in both New Hampshire and Maine, however, are descended from a small group of just thousands of people who came to New France before the French Revolution, which transformed the language as much as the politics.

“The French in New France were still living that old culture and that old language,” says Robert Perreault, a Franco-American author and French teacher in Manchester. “They evolved in a different way.”

In the New World, for instance, settlers learned to harvest and eat maple syrup from the native people who lived here; they had to incorporate those words into their language. Over time, Quebecois French naturally diverted from European French in small ways; a person in France would say pas du tout for “not at all,” while a Quebecois person might says pantoute.

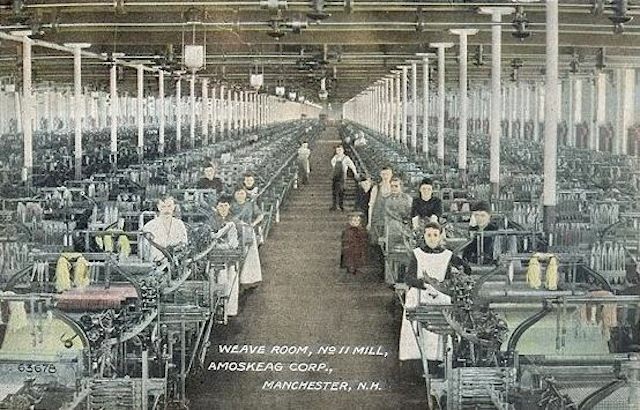

A Manchester mill in 1910 (Image: Wikimedia)

For the most part, the Franco-Canadians who would later immigrate to New Hampshire spoke an agrarian French, concerned with the life and routines of farm life. When they migrated south to work in textile mills in the 19th century, they didn’t have a technical vocabulary to describe the work they would do.

As a result, the French that’s spoken in New Hampshire is filled with French-inflected English words to describe 19th century mill work. In French, the word for “to weave” is tisser. But in New Hampshire, French speakers are more likely to say weaver–je weave, tu weaves, nous weavons, vous weavez. Instead of filer, the French word for spinning, they would say spinner.

“They would take an English prefix and an French suffix and make a new word,” says Perreault.

In Manchester’s heydey as a mill town, the west side of the city was the territory of the Franco-American immigrants. The east side was more Irish, and “if you go back a couple of generations, it would have been a big family scandal if someone from the west side was dating someone from the east side,” says Tousignant. The Ste. Marie church, which still stands today, was a focal point of the west side of the city, and the same area had La Caisse Populaire, America’s first credit union.

Manchester’s Sainte-Marie church (Photo: John Phelan/Wikimedia)

Manchester’s Sainte-Marie church (Photo: John Phelan/Wikimedia)

Back at the turn of the century, it was still popular to trace New Hampshire’s Francophone population back to particular areas of Québec. The plurality of French-speaking people in Manchester had come from the Richelieu River valley, north of Lake Champlain and east of Montréal. Another large group came from the Beauce region, south of Québec City and north of the border with Maine. A number of people also came from New Brunswick, the province of Canada that’s to the northeast of Maine, where people spoke a somewhat different variety of French than the Quebecois.

Even today, says Tousignant, “we could talk about the difference between someone speaking French in Berlin and someone speaking French in Manchester.” Berlin has always been a blue-collar community. “The type of French they speak is more earthy,” says Tousignant.

It’s also in danger of disappearing entirely. Once, Catholic schools in New Hampshire taught students for half the day in English and half the day in French, but today, only a fraction of Franco-Americans in New Hampshire speak French at home. Tourtière, on the other hand, is harder to give up.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook