How to Get a Boat Through a Tiny Tunnel, 19th-Century Style

This will be difficult and you might die.

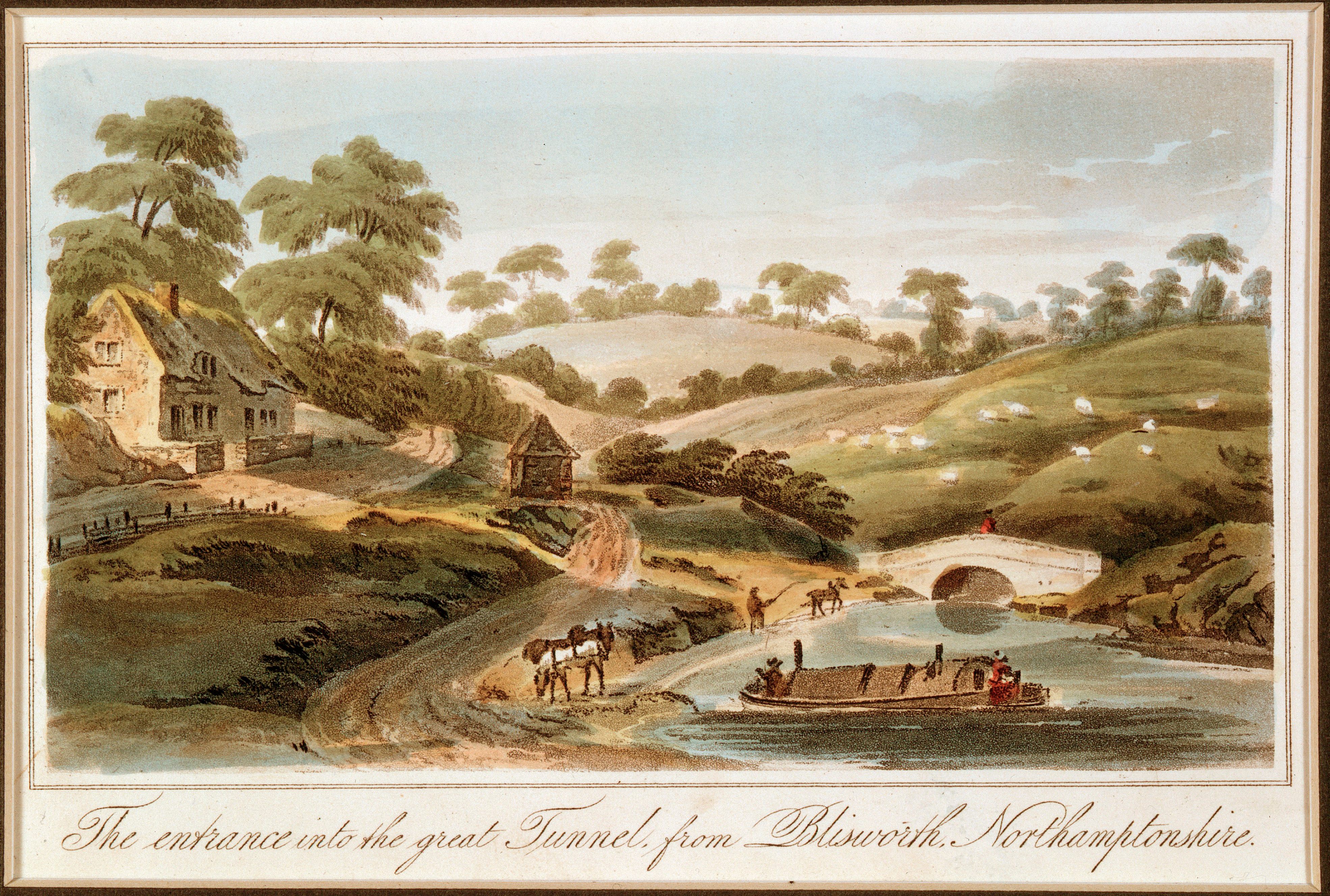

On a recent summer day in Northamptonshire, England, Kieran Boughan, 66, found himself seated on the triangular front deck of a motorized narrowboat along England’s Grand Union Canal—awaiting entry to the canal’s 1.7-mile-long Blisworth Tunnel. After hours meandering through the pastoral landscapes bordering the waterway’s riverbanks, past quaint country villages and wide-open meadows, Boughan knew the tunnel would be a drastic change: its pitch-black and oppressive cave-like interior; the eerie echoing of water dripping from its curved walls and rooftop; and a drastic drop in temperature as the boat traveled slowly through the long, damp passageway in no more than five feet of water.

As Europe’s longest, freely navigable tunnel wide enough for two boats to pass, Blisworth is just one of more than two-dozen canal tunnels dug during the United Kingdom’s Industrial Revolution in the 18th and early 19th centuries. This was a time when engineless narrowboats—pulled by horses that walked along a canal’s towpaths—transported mass quantities of goods like coal, iron, and pottery along a “super highway” of inland waterways and their locks, tunnels, and aqueducts throughout Great Britain, eschewing muddy and rut-filled primitive roadways for these easy-to-use, large-capacity canal systems. Still, it was the tunnels that Boughan was most excited to experience, because they’re the whole reason that “legging” exists.

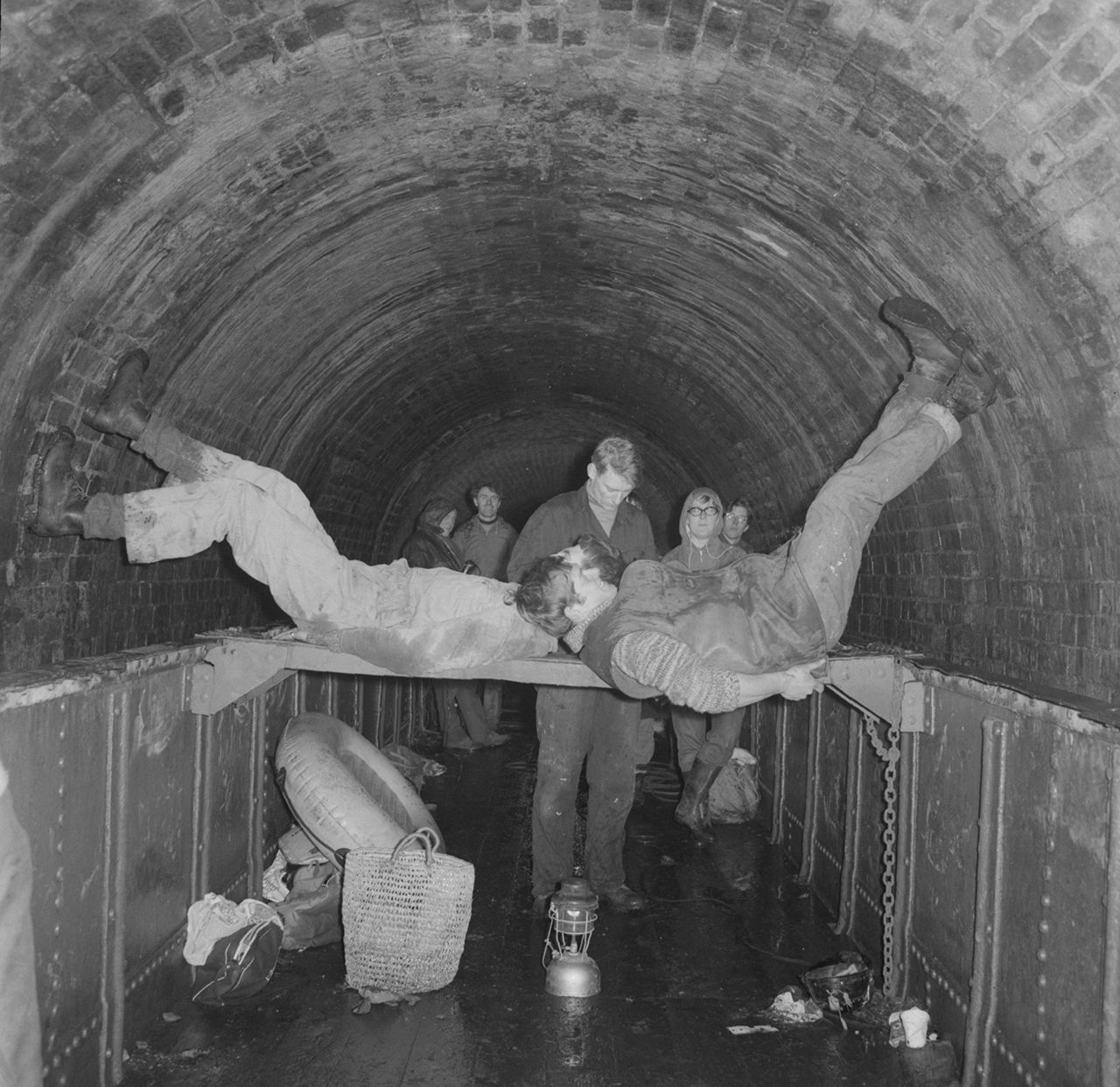

Legging is the act of moving a narrowboat through a canal tunnel, while lying on your back either atop the boat or—as was most common—on a plank jutting out across its bow at both sides, and walking along the tunnel’s roof or walls. It usually requires two people, one on either side of the boat and each holding onto the plank for stability, keeping their legs at a 45-degree angle as they “leg it” with equal pressure through tunnels that could stretch over three miles long (at 3.24 miles, it would take leggers approximately 1 hour, 20 minutes to leg through Standedge Tunnel with an empty boat, and three hours with a full load). It was an actual profession during the Industrial Revolution. While the legging was being done, a tunnel keeper or the boat owner would unhook the boat’s pull horses and lead them up and over the hillside to the tunnel’s far end, reconnecting them when the process was complete.

“Have you heard a person say they’re ‘legging it,’ meaning going somewhere, preferably fast?” asks Judy Jones, Heritage Advisor for the U.K.’s Canal & River Trust, an organization that overlooks the care of more than 2,000 miles of canals and rivers in England and Wales. “This is where that expression comes from.”

But “legging it” is far from efficient—it’s a job that came out of necessity. Although canal systems in much of the rest of Europe developed at a much slower pace, the U.K.’s rapid industrialization meant that construction had to be done swiftly. “[The companies and individuals] building these canals were on a tight budget and didn’t think the canals would still be functioning in two- or three-hundred years. They didn’t really care. They needed to get them done and get them open quickly,” says Jones. Building a tunnel with a towpath and one high enough for a horse to walk through would increase costs considerably, so many times they skipped the towpath completely and made their tunnels just wide enough for the boats, which could be no more than 70 feet long and approximately 6 feet 10 inches wide.

Tunnels like Shrewley Tunnel in England’s West Midlands added rails that boaters could use to pull their way through. In other instances, boaters propelled their vessels with poles. Legging, however, was the most common technique for getting a boat through a tunnel, albeit one that was harrowing, hard, and extremely dangerous, especially in such dark, narrow, and closed-in spaces. “It wasn’t glamorous by any means,” says Jones. “There were loads of fatalities.”

There was the constant drip of water in some of the more damp, poorly ventilated tunnels, making the surfaces slippery; and although many of the tunnels were lined with stones or bricks, others had sections that were completely cavernous, so that a legger could misstep easily. Boughan was amazed at how difficult a job it must have been. “You can imagine how the weight of the boat could trap one of the person’s legs, or even their entire body, if the opposite legger accidentally pushed too hard,” he says.

Dizziness was common, and the slow and arduous process of seemingly endless walking (“You had to keep moving,” says Jones, “because there were boats waiting at the other end.”) was exhausting, causing leggers to sometimes fall off the planks between the boats and the tunnel walls.

While working, leggers often stuck a sack of grain between their backs and the plank to help ease discomfort, and stuffed their boots to keep their feet cushioned when the tread inevitably wore down. “The trick to the job was to get a really good rhythm going between the two leggers,” says Jones. “If they could do this, it made the work a lot easier.”

Alison Smedley, Policy & Campaigns Official for the U.K.’s membership-based Inland Waterways Association, says that it was only the longer tunnels—such as Blisworth, Dudley Tunnel in the West Midlands, and Britain’s “longest, deepest, and highest canal tunnel,” the 3.224-mile-long Standedge Tunnel in West Yorkshire—that actually had their own legging teams. At Standedge Tunnel, official leggers eventually became the law. “On the shorter tunnels boaters were expected to get their vessels through on their own,” she says, which meant that the wives of some boaters were more than likely legging it through as well.

Still, being a legger was really a last resort, one reserved for men looking for whatever work they could find. “When people are desperate they’ll do anything—even if it’s for a shilling,” Jones says. Blisworth Tunnel, in particular, was notorious for its ”unofficial” leggers who would often terrorize boaters into employing them. “This was a time when many considered the boating community to be the fringes of society—there were families living on their boats, sometimes with five kids on board, hauling things up and down the river,” says Jones. “People referred to them as ‘Water Gypsies,’ and leggers were on the fringes of this community.” A typical legger was likely male and uneducated, a bit older—in his 50s or 60s—and unable to get work in other fields. “[These men] hung around at the entrance to tunnels and just waited. You have to think they had very little options,” she says. “I mean, three hours legging it through a damp, dripping, claustrophobic place where you can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel? It’s an awful existence, really.”

Although ”wing” boards, which hooked directly on to a boat to provide added stability, soon came onto the scene and made legging slightly safer, the profession was thankfully short-lived. Steam and electric tugboats eventually replaced horses and in the 1920s motorized boats appeared, making legging almost obsolete.

Many of the U.K.’s most famous legging tunnels remain today, including Blisworth Tunnel, which features the Canal Museum of Stoke Bruerne—with a gift shop full of canal-themed maps and literature—at its southern end, and two-mile-long Dudley Tunnel. Because of its poor ventilation, the latter still requires either an electric pull tug or a team of leggers for boats that want to travel through. In fact, the Dudley Tunnel Trust (part of the larger open-air Black Country Living Museum) even allows visitors to give legging a go along a small portion of its largely limestone tunnel. Anyone with their own or a hired gunnel-height boat, meaning no higher than the top of the cargo carrying level, can also leg it all the way through by arrangement.

Smedley, who lives on her own ex-cargo-carrying boat from the 1930s, has actually done it.

“The first time we tried legging it through Dudley Tunnel there were only three of us on board and it took us three hours—with two of us legging and one of us taking a rest. The second time we had eight people on board, so we had four people legging and four people resting at any one time. Then we hopped out and swapped over, and we did it in two hours.”

But it was the tunnel’s nostalgic ambience that Smedley found most appealing. “Often when you’re taking a narrowboat through a tunnel you’ve got all the noise and the fumes of its diesel engine, because they really have nowhere to go,” she says, “but when you’re legging it through you can hear every little sound—it might just be cobwebs or a bit of debris that you’ve dislodged and it plops into the water, but you just hear it. It’s very atmospheric.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook