The Cider Makers Who Bury Their Booze

A Virginia cidery has adapted an 8,000-year-old winemaking method.

Don Whitaker, the Cider Maker at Castle Hill, strolls over a grassy knoll in one of Virginia’s oldest historical estates and approaches what looks to be a graveyard. The lower half of a huge, broken urn stands before the entrance of a roped-off gravel square surrounded by mature linden trees, sprawling fields, whitewashed horse fences, apple orchards, and a horizon of Blue Ridge Mountains.

“One of the qvevri broke when we were getting them shipped across the Atlantic,” says Whitaker, 51, pointing at the urn.

What appears to be a cemetery is actually a place for burying and fermenting booze. Known as qvevri, the egg-shaped terracotta vessels are about nine feet tall and hold 300 gallons each. Cement boxes protruding from the ornamental gravel are chimneys that offer access to stainless-steel tops and rubber ports retrofitted to fit them.

Castle Hill Cider launched outside of Charlottesville in 2010 after importing 12 of the traditional handmade containers from the Republic of Georgia. There, villagers have been burying qvevri and using them to make wine and other alcoholic beverages for about 8,000 years. The containers are believed to be one of the world’s oldest large-scale fermentation technologies, and UNESCO has designated qvevri wine-making as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

“We’re the only commercial cidery on the planet using these,” says Whitaker, who ferments heritage apples in qvevris to make one of the world’s most novel dirt-to-glass ciders. Known as Levity, the vintage has won many accolades, including a 2018 Good Food Award.

This wild-fermented cider is funky, delicious, and utterly unique, says renowned cidermaker Diane Flynt, a two-time James Beard Foundation Best Wine, Beer, and Spirits Professional finalist. “It’s very, very special.”

Whitaker calls Levity a high-end adaption of the estate ciders touted by early American connoisseurs including Thomas Jefferson and Ben Franklin. But its roots go deeper than that. Visitors to Castle Hill can experience millennia-spanning flavors that are more closely related to humanity’s first fermented beverages than modern vintages.

The team behind Castle Hill did not originally intend to adapt ancient Eastern European fermentation techniques. They didn’t even plan to make cider. Instead, in 2009, the owners of the colonial-era estate hired landscape architect Stuart Madany to design gardens and grounds for a vineyard.

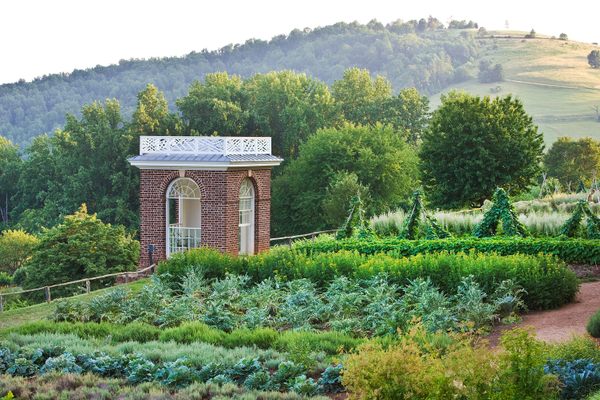

Castle Hill’s owners hoped to capitalize on its history—the estate was formerly owned by Thomas Walker, a physician who served as Thomas Jefferson’s guardian—and the Virginia wine boom. But as Madany pointed out, the property had once featured extensive apple orchards, most of which were used to make cider. (Like at Jefferson’s Monticello, most were installed and tended by enslaved people.) Considering Virginia already had more than 100 wineries, why not focus on cider instead?

“This area was a historical haven for cider,” says Whitaker. Jefferson planted experimental orchards at Monticello. In the early 1800s, the nearby Shenandoah Valley was the largest apple-producing region in the United States, and its pomologists grew thousands of heirloom varieties. Yet in 2009, there were just two craft cideries in Virginia; ditto for heirloom apple orchards.

Fortuitously, a food-foraging friend of Madany’s had recently found what was left of a forgotten, 100-year-old apple orchard on a family property near Shenandoah National Park. Identification revealed numerous prized historical cider varieties, including the Albemarle Pippen, Hewes Virginia Crab, Harrison, and Black Twig. The trees could provide foraged apples and scionwood for an orchard.

“I’d long been fascinated by the idea of growing rare heritage apples organically and trying to recreate historic farmhouse ciders,” says Madany.

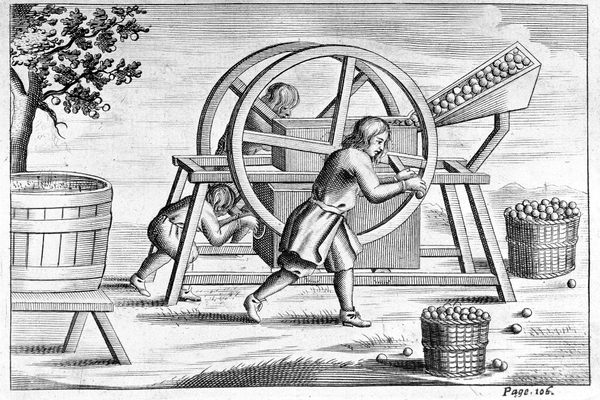

Colonial and early American farmers crafted ciders in the manner of estate wines. Farm-grown apples were pressed, then slow-fermented through the winter in cellar-kept barrels using wild yeasts. The beverages were thicker and hazier than modern commercial ciders, and featured complex and slightly bitter apple flavors. Like sour beers, tastes were robust and fruity, and could include hints of lemon pith, sage, wild berries, bleu cheese, stone fruit … the list goes on.

Madany wanted to expand on the method to create something that was both new and historical. Previously, while backpacking in Eastern Europe, he’d heard that Georgian villagers made wild-fermented wines in huge earthenware jugs buried below the frostline. He had visited farm vineyards and learned how winemakers crushed grapes and put them into the vessels along with stems and skins.

Vintners told Madany qvevri are like a mother’s womb. First, the land gives birth to grapes, then they help the qvevri give birth to wine. Villagers sealed the terracotta containers with a thin coat of local beeswax prior to harvest. Constant subterranean temperatures around 43 degrees brought a smoother, slower fermentation—ideal for volatile wild yeasts. Grape stems and skins imparted bold and earthy flavors. The beeswax, a subtle floral sweetness.

“Another thing is the absence of wooden barrels,” says Whitaker. Barrel-fermentation and aging conveys woody overtones. Stainless steel can bring anesthetic harshness. “But qvevri are almost transparent. They work hand-in-hand with nature and let the fruit sing in a manner that is very, very distinct.”

Madany believed qvevri wine-making methods could be applied to apples to make the ultimate farmhouse cider. Castle Hill already had an apiary. They could import qvevris and use apples foraged from the lost grove while they installed an heirloom orchard and tasting room.

The estate’s owners loved the idea and asked Madany to be their cidermaker. Within a year, he was consulting with Georgian winemakers about purchasing qvevri.

Adapting qvevris to cidermaking required lots of experimentation. “There were no templates, it was all trial-and-error,” says Whitaker, who joined Castle Hill about five years ago and took over for Madany in 2019. The team tried different combinations of apples to see which performed best in qvevri, and they made mistakes: One early lid design without proper venting led to an explosive “belch” that expelled gallons of cider.

But the effort was worth it. By 2017 Castle Hill was crafting about 500 cases of Levity a year and winning regional and national awards. In 2018, Garden and Gun Magazine named it a runner-up for the best alcoholic beverage in the South. The 2019 vintage was crafted from 10 heritage varieties: Harrison, Albemarle Pippin, Golden Russet, Ashmead’s Kernel, Winesap, Bramley’s Seedling, Golden Hornet Crab, Dabinett, Chisel Jersey, and Puget Spice. It was fermented for four months in qvevri, then bottle-conditioned to let yeasts create natural carbonation reminiscent of champagne.

Of Castle Hill’s roughly 10 offerings, “Levity is definitely the closest to my heart,” says Whitaker.

On one hand, it’s a craft product unlike any in the world. On the other, it lets him tell the story of historic Virginia cider within a context of global fermentation traditions that span millennia.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook