A Visit to the Biggest Little Mosque in Honduras

The sky-blue building draws a diverse range of Muslims from hours away.

Honduras is a country of churches. There’s the buttercream facade of Santa Rosa de Copan’s Roman Catholic cathedral, the Mission revival-style St. Peter the Apostle cathedral in San Pedro Sula, and the geometric grid of the Latter Day Saints’ church in Tegucigalpa. Crosses dangle from necks and rearview mirrors and are you adorn tombs in graveyards across the country. Christianity—be it Catholic, Protestant, or, increasingly, Mormon—dominates the landscape.

But nestled on a quiet street in the country’s second-largest city of San Pedro Sula is a different kind of religious sanctuary. Half shielded by palm trees, it’s set back from a parking lot, so it’s not entirely noticeable at first glance. The gold-covered qubba (domes) pointing upwards and topped with crescent moons are unmistakable, though, and if you strain your ears on a Friday afternoon you might hear the faint call to prayer. Welcome to the only mosque in San Pedro Sula, and one of just two in Honduras.

Pakistani factory owners, converted Honduran military generals and Cuban flaneurs are just a few of the people who attend jumu’ah (Friday prayers). Imam Mohammed, who leads the service, estimates there are around 1,500 Muslims in Honduras, though Pew Forum research put the number closer to 11,000 in 2009. Regardless of the total, only around 30 people attend prayers at the mosque on a weekly basis.

Arnaldo Hernandez, a Garifuna fisherman, drives three hours from his home in the coastal town of La Ceiba to attend Friday prayers. He converted to Islam from Christianity 26 years ago, though, as he is quick to point out with a huge grin, “we are all Muslims.”

Hernandez is one of the older members of the community, before there was even a physical mosque. “We used to pray in a room close to the hospital,” he explained after jumu’ah. It’s not uncommon in non-Islamic countries for Muslims to pray in makeshift locations when proper mosques are nonexistent. In towns across Italy, Muslims pray in warehouses and supermarkets; in Hong Kong, devotees worship in a former car repair shop.

Latin America has the largest Arab population outside of the Arab world. For many years, Honduras was the only Latin American country without a mosque—despite the fact that up to 25 percent of San Pedro Sula’s population is of Arab descent. Now, there are two: the one in San Pedro Sula, and a smaller one in the capital city of Tegucigalpa.

The introduction of Islam to Honduras is linked to the waves of Arab immigration, explains Rodolfo Pastor Fasquelle, a historian at San Pedro Sula’s Museo de Antropologia e Historia.

“In 1870 the national railroad pact was signed with the British,” Fasquelle said, while giving a tour around the museum’s exhibit of 19th-century artifacts. “It was a great fiasco—it never got past the mountains—but it did connect San Pedro Sula to the coastline. And as the city became an internal port, it became crucial to trade with the outside world.” Goods came, and so did immigrants from Europe, North America, and increasingly, the Middle East. Arab migration came in three waves: from 1895-1915 as the Ottoman Empire suffered a string of crises; from 1925 to 1940 in the wake of the First World War; and again from 1950-1970, after visas became easier to obtain.

The first two waves of migration were mostly comprised of Christian Arabs; records from the time indicate that only 15 percent of immigrants were Muslims. Regardless of religion, at the turn of the century most migrants arrived in Honduras with an Ottoman Empire passport, earning them the nickname “Turcos,” a generic and incorrect identification that still holds today. After 1925, many of the Arab immigrants came from Palestine, notably around Bethlehem. These Palestinian migrants were well-educated, multi-lingual, and had strong social networks and business ties that allowed their community to flourish. Given their skills, many were able to work with U.S. companies in the lucrative banana and tobacco industries.

By 1918, Arab immigrants owned over 40 percent of businesses in San Pedro Sula. Although Arab immigrants, according to a 1929 law, had to deposit $2,500 upon entering the country, they had more capital to buy land and set up business than indigenous Hondurans did. Even with legal restrictions, by 1979, 75 percent of San Pedro Sula stores were Palestinian-owned. “They became a part of the social fabric,” says Fasquelle. Despite accounting for 3 percent of the country’s total population, Arab Hondurans evolved from a merchant class to one dominating the business, political, and economic environment.

Though the Arab population is well-integrated today, many Hondurans view “los Turcos” as land-owning oligarchs. Part of the image problem might come from the Club Hondureño Árabe, a country club located in San Pedro Sula’s ritziest neighborhood boasting an $8,000 initiation fee—the country’s average monthly salary is less than $300. Founded in the 1960s as a cultural space for the Arab community, the club has ballooned into a $15 million complex that hosts elaborate Levantine brunches, lavish weddings, and sports tournaments. Until 1994, members had to be of Arab origin; the club has since relaxed its rules to allow anyone who can pay the membership dues.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t deep-rooted biases or tensions against Muslims within the Arab community. When asked if the Arab community thought Syrian refugees should be granted asylum in Honduras, one club employee exclaimed “No, thank God!”

Honduras’s constitution protects freedom and practice of religion—though the government only officially recognizes the Roman Catholic church; all other religious groups are categorized as religious associations and have fewer rights and privileges. Despite the institutionalized imbalance, and Honduras’s generally high crime rate, religious violence and discrimination is low. “We haven’t had any problems with racism,” says Mohammed, the Pakistani-born temporary imam of the mosque.

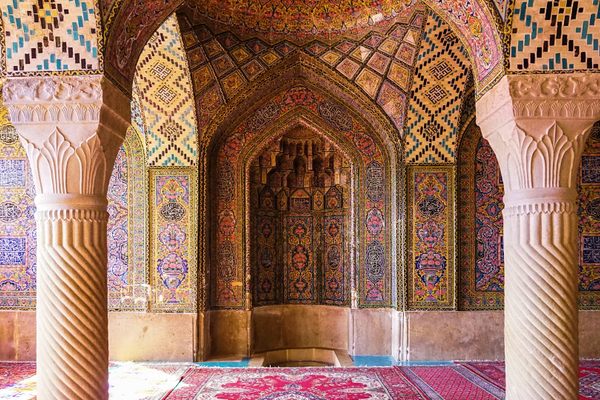

Mohammed invited us to attend the men’s prayer, which he led in a mix of Spanish and Arabic. The decorations are the same as any mosque in the world: green carpets, gilden Quranic verses. Outside, you could bite into the Honduran humidity like a marshmallow, but inside it was air-conditioned and cool. The men slowly trickled into the room over the next hour, and performed their prayers; a few older gentleman with swollen ankles sat on plastic stools. We could have been anywhere in the world—Turkey or Tunisia or the Comoros—but we were in San Pedro Sula.

“I started studying Islam alone, and the path of Allah came for me,” Colonel Orlando Ajalla Gaños told us. Raised Catholic, the colonel has spent the last nine years commuting weekly to the mosque from his home in Tegucigalpa. “I was always happy but since becoming Muslim I am even more happy—you can call me Saif,” he added, referring to his Islamic name as he adjusted his taqiyah (cap).

Perhaps because the community is so small, there is a real sense of camaraderie among the worshippers. After prayers, they laugh and joke out in the parking lot. There are weekly dinners organized by Mr. Yusuf, a Pakistani Muslim who owns a string of factories and is one of the country’s richest men. Everyone contributes to the mosque’s upkeep—a donation box is passed around after the prayers. In this sky-blue Caribbean mosque, the best parts of Islam—equality, fraternity, love—seem to shine.

“There’s no distinguishing between race and color. We are all brothers, that’s the base of Islam,” Hernandez, the Garifuna fisherman, said. “It’s a benediction to have this community.”

Reporting for this story was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation as part of its Adelante Latin America Reporting Initiative. Special thanks to Jenny Núñez and Catty Calderón.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook