What Happened to Montreal’s Legendary Melon?

A medley of efforts, and one abbey’s monks, may bring back the forgotten fruit.

A century ago, Manhattan residents with a hankering for dessert might flick on their finest frock coat, get a table at a white-tablecloth restaurant, and order a juicy slice of Montreal melon. It didn’t come cheap, though. A slice of the green-fleshed melon sold for a steak’s price of $1, or around $30 in today’s currency.

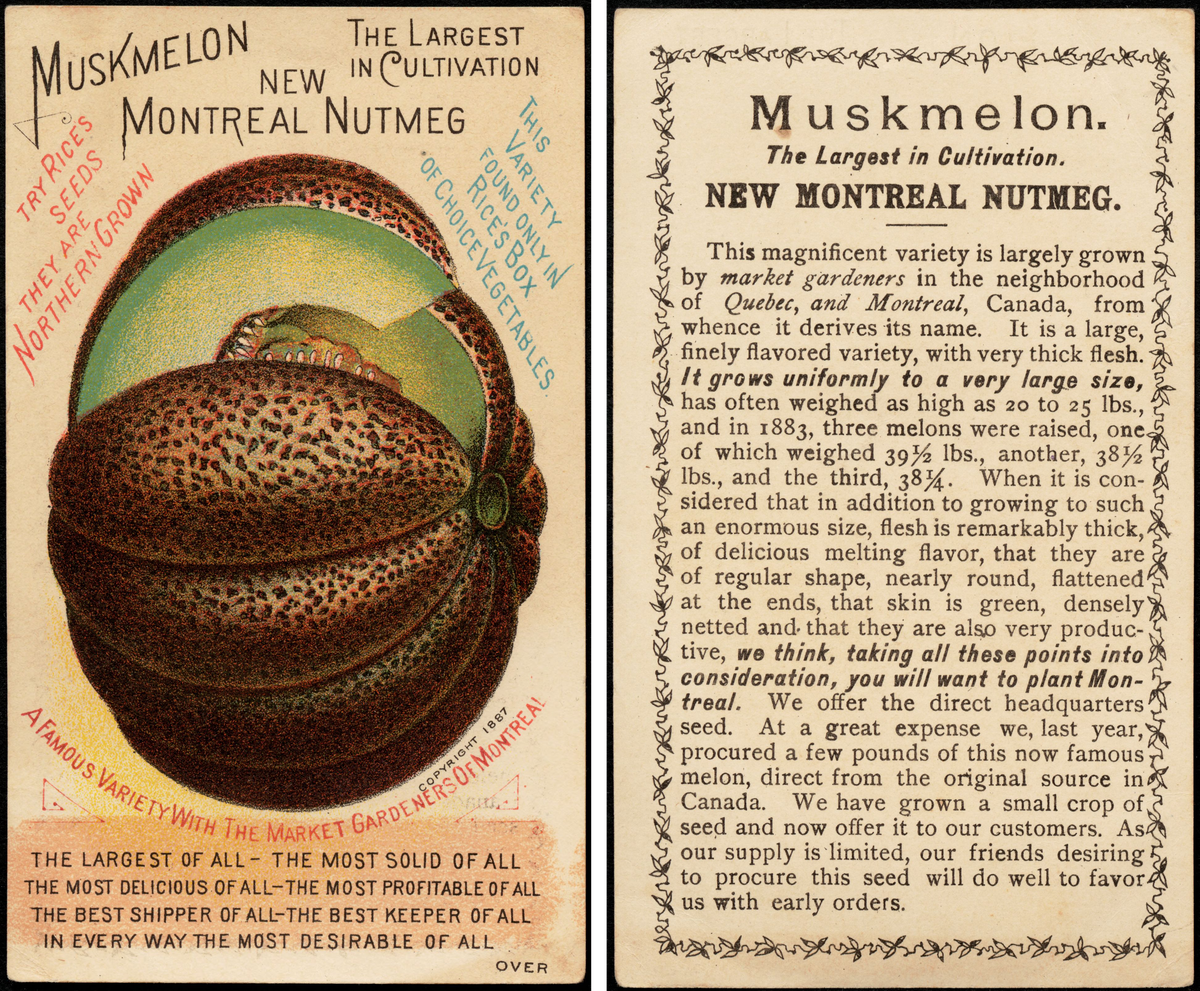

In its day, the Montreal melon was the Champagne of melons. An 1885 newspaper described it as “of the largest size … almost round, flattened at both ends, and deeply ribbed, skin green and netted, flesh very thick and of finest flavor.” Some whole melons weighed more than 40 pounds, and the Queen of England received one every year, carefully wrapped in a wooden basket designed to protect the delicate fruit.

But then the Montreal melon disappeared. And then it came back, then died again. But now its offspring is being grown once again, resurrected by a group of Trappist monks in an abbey northeast of the city.

“The Montreal melon has a storyline that no other fruit or vegetable has,” says journalist Barry Lazar, who was the first to write about the prodigious produce in recent memory, in his 1991 article in The Montreal Gazette.

Also known as a muskmelon or nutmeg melon, the Montreal melon first piqued Lazar’s interest during a walk around his neighborhood.

“I was looking at the street I live on, which is Old Orchard, and sort of wondering about what the community was here and realized that there were basically farmers’ fields that were set up,” he says. “We’re talking into the 18th century or before.”

Lazar’s urban Montreal neighborhood, Notre Dame de Grâce, was once farmland with a sunny slope, perfect drainage, and rich soil fertilized with horse manure collected from the city’s four racetracks. But as the city grew, houses supplanted the farmland and the Montreal melon lost its fertile ground.

“As the horse manure decreased, the farming decreased and housing increased,” Lazar explains.

After writing about the melon, Lazar’s colleague at the Gazette, Mark Abley, couldn’t get the story out of his head. As far as Lazar could tell, there weren’t any seeds to be found, but Abley managed to track some down at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s collection in Ames, Iowa.

When the small brown envelope of seeds was delivered to the newspaper office, Abley was ecstatic. He knew there was just one person he could entrust to get them growing again: Ken Taylor, an organic farmer just off the island of Montreal in Île Perrot. Taylor worked as a chemistry professor at a local college, but his real passion was growing organic and heirloom fruit, such as Asian pears and some 300 varieties of tomatoes, that people don’t expect would grow in Montreal’s climate.

“Every fruit you can think of, I’ve got an angle and I’m working on it,” says the now 77-year-old.

By the fall harvest, Taylor had managed to grow melons that’d make a turn-of-the-century New Yorker twiddle their mustache in fierce anticipation—some weighed as much as 25 pounds. Taylor passed seeds onto hobby farmers and seed companies in subsequent years, and a local historical association made T-shirts with the iconic fruit printed on them for a fundraiser.

“A lot of people didn’t get stuff going on, but I do know of people who [succeeded at growing Montreal melons], and I was able to eat some,” Lazar says. “I thought it was superb. It tasted like a combination of a cantaloupe and a honeydew when it was perfectly ripe, and someone actually made a jam out of it, which they gave me, and that was really quite delightful.”

Taylor grew the melons for four or five years, selling them to a local grocery delivery company and giving seeds away to anyone who asked.

“It had that nice green flesh, spicy, a little nutmeg aftertaste. Very sweet, very nice,” he says. “But many years you grow them and they don’t turn out very well.”

The problem is that the Montreal melon is extremely temperamental. You have to plant them earlier than other melons, put them in an airy place, and lift them off the ground. Even with all that pampering, they require perfect weather. Seed companies didn’t want to continue growing the melons themselves, and Taylor wasn’t interested in growing them long-term.

Thank God for the monks.

Back when the Montreal melon was wowing New Yorkers at the turn of the 20th century, Trappist monks in Oka, a short drive northwest of Montreal, were working on new food products at their agricultural school.

They developed Oka cheese (perhaps Quebec’s best-known cheese), the Chantecler chicken (adapted to the province’s harsh winters), and, in 1912, Brother Athanase Montour crossed the Montreal melon with a banana melon to create the Oka melon, which has orange flesh and about 10 ribs.

As Quebec separated church and state, the agricultural school was handed over to a university and the Oka melon drifted from memory as cantaloupes like the Athena variety, which are common in grocery stores today, won the popularity contest. But like its legendary green-fleshed relative, a couple of coincidences brought it back.

Fifteen years ago, Jean-François Lévêque, an organic farmer passionate about heirloom seeds, was looking through the Seed Savers Exchange and stumbled across the Oka melon. He’d heard of the legendary Montreal melon, but found himself just as intrigued by the Oka monks’ variety.

Lévêque’s farm, Jardins de l’Écoumène, just so happens to be a few minutes from the Oka monks’ new monastery, Val Notre-Dame Abbey in Saint Jean de Matha. So, in 2014, he brought the monks Oka melon seeds and was surprised when they had no idea what he was talking about.

“They had forgotten that it was their community that had [invented them],” he says. “Then, when I spoke to them about it, they were very enthusiastic about the idea of actually cultivating it again.”

The monks planted the seeds, and the Oka melons grew once again. They now grow about 40 well-formed melons a season, all of which feed the 18 remaining monks at the abbey. Hobby farmers are growing the Oka melon, too, thanks to seeds sold by Jardins de l’Écoumène and Nutritioniste Urbain, which sells them in an heirloom seed party pack.

Brother Bruno-Marie Fortin, a monk for 48 years, says that he prefers the Oka melon’s taste compared to your average supermarket cantaloupe, but that’s not the reason they grow it.

“The important thing is: It is a tradition,” he says. “The monks were teachers of agriculture. They wrote several books on agriculture, [then] the link was broken. But by reintroducing the Oka melon, we find ourselves recreating, a little bit, the link with our agricultural past.”

And so the Oka melon lives on, at least amongst monks and gardeners. Yet its parent, the Montreal melon, does not, or at least not substantially. Which begs the question: Is it worth the hassle of growing finicky heirloom fruit?

For Taylor, it’s more worthwhile to preserve fruit varieties that grow well and taste delicious. In his view, a MacIntosh apple isn’t worth saving when there are tastier options out there. “And neither is preserving the Montreal melon, just to put it bluntly.”

Yet for the Trappist monks and Lazar, the melons are worth the hefty price, if not only for the joys of telling its juicy story.

“It didn’t exist. Then it existed, it became famous, became really big and became really important … and then it died,” Lazar says. “So it’s got a beginning, a middle, and an end, and there are not many stories about fruits or vegetables that you can say that with.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook