The ‘Moby-Dick’ Musical Is Swimming With Sea Shanties and Nurdle Ballads

We watched it with a whale anatomist to see if the cetacean science holds water.

Joy Reidenberg and I sit on folding chairs, directly under the 21,000-pound, foam-and-fiberglass replica of a blue whale that arches from the ceiling of the American Museum of Natural History’s Milstein Hall of Ocean Life in New York. We’re talking about Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.

“It’s very long,” she says. “And it’s very detailed. You have to really want to read it.” That’s 135 chapters, plus an epilogue, and Reidenberg and I have both sailed through it. She wasn’t so much in it for the story—the tale of the crew of the Pequod and its captain’s single-minded stalking of the ornery sperm whale that made off with his leg. Rather, she says, she read “for the accuracy of the descriptions of whales.” Reidenberg knows whales inside and out—literally. She is a comparative anatomist at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine specializing in cetaceans, and she often dissects them when they appear on beaches around the city. Not only that—she’s a fan. She had arrived to the museum that July day wearing a sperm whale T-shirt, and told me she often sprawls out beneath the blue whale, even when the museum is crowded, to imagine what it would feel like to see a giant like that passing overhead.

We’ve met at the museum to see a staged reading of excepts from composer Dave Malloy’s new musical adaptation of Melville’s novel, ahead of the production’s debut in December 2019 at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Reidenberg and I were there to listen to the songs the same way Reidenberg read the novel—with special attention to the marine mammals that inhabit them.

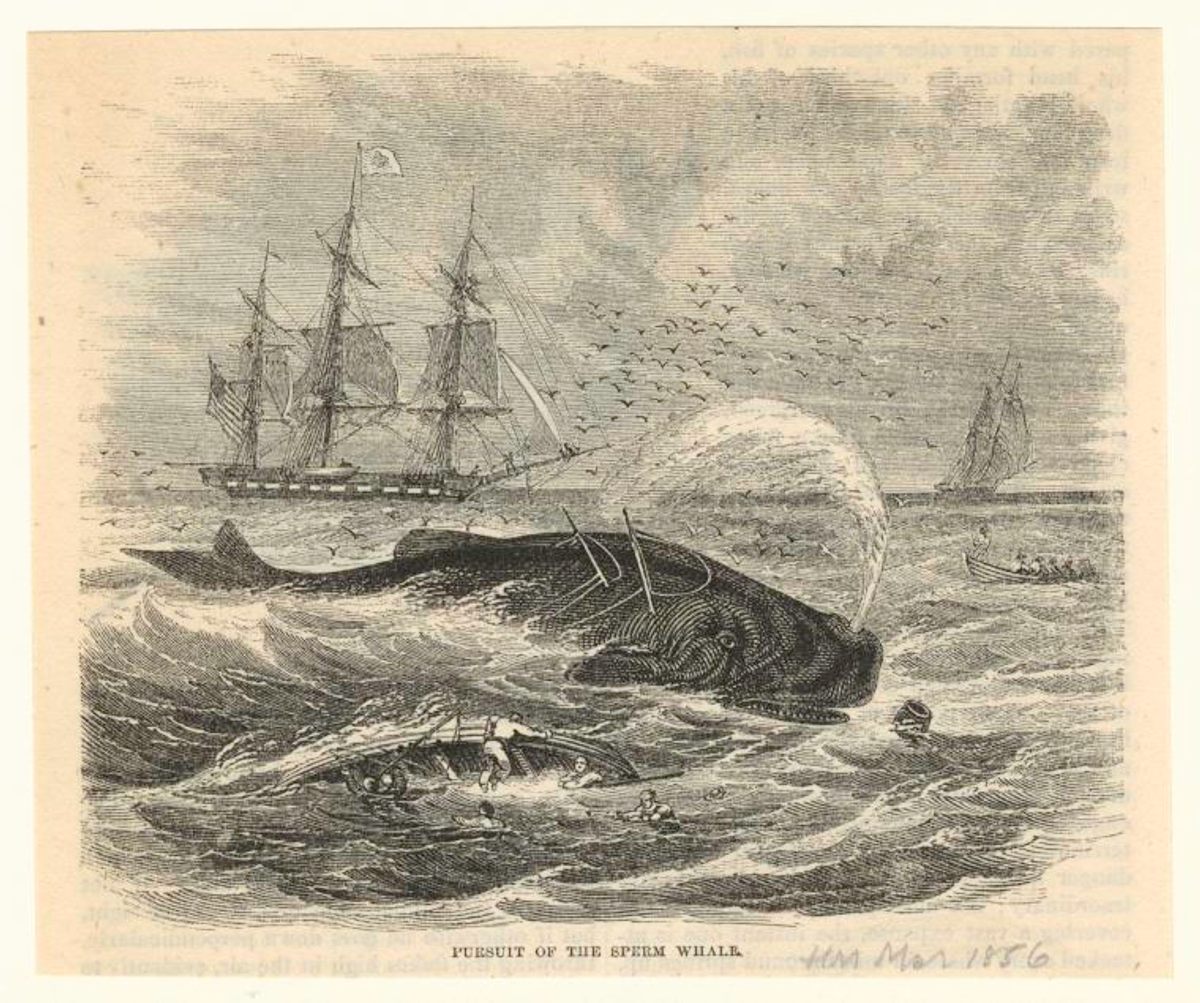

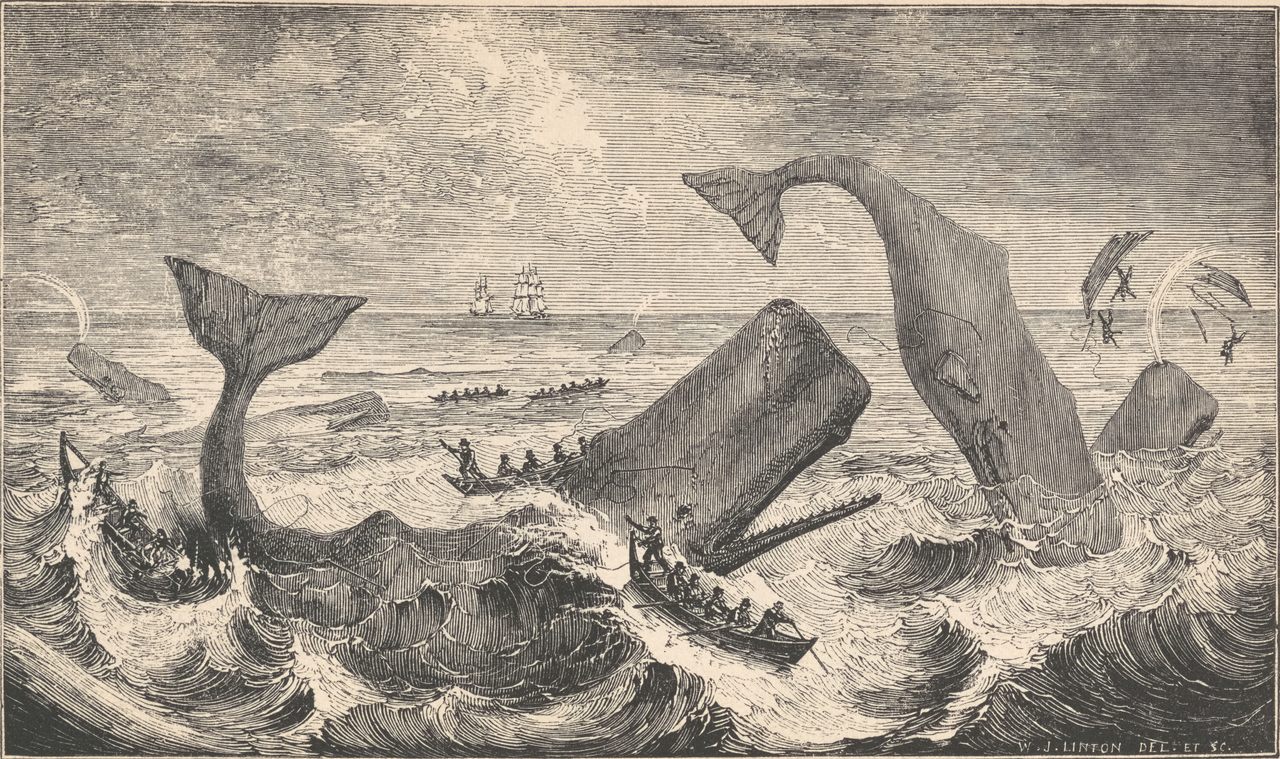

“I was very impressed with how much anatomy [Melville] knew and how much biology he knew,” she says. Melville had drawn on several sources to learn about whaling, in addition to his own experience at sea, and based his eponymous character on tales of Mocha Dick, a sperm whale “as white as wool” that infamously troubled whaling crews for several decades in the 19th century. The book is notorious (and sometimes knocked) for dense, detail-packed passages: entire chapters devoted to whale skeletons, to the “fountains” erupting from blowholes, to spermaceti, the slick, thick, multipurpose oil found in sperm whales’ heads.

“Let us, then, look at this matter, along with some interesting items contingent,” Melville writes, as he clears his throat before one such chapter, packed like a clot of seaweed. It works on the page, sure, but will any of it make sense when sung to the rafters above the blue whale model? I was eager to see how Malloy’s production would handle the detailed information that makes up so much of the novel. Reidenberg agreed to be my guide to the literary whale world.

The performers and musicians—including a cellist, hornblowers, percussion, and Malloy, on the piano—are on a small, undressed, elevated stage, clad in street clothes. A long platform juts out from the stage, and surrounded by a room full of spectators sitting around it or up in the balcony, surrounded by waterless dioramas of the sea. With only a brief prologue and a single “Call me Ishmael” joke, the cast launches into it, beginning with the novel’s first page. Nick Choksi—call him Ishmael—recites much of Melville’s language about a journey to sea being the only salve for a morose spleen and the urge to doff people’s hats. The songs that follow tell the entire story, often with the original language, but the novelty of the performance rests with its winking updates.

The staged reading doesn’t include all of the final songs, and doesn’t really wade into the densest passages of maritime and scientific exposition. But during one interlude, Malloy runs down a few of the scenes that will augment the full version, including an extended depiction of whalers extracting spermaceti and slicing meat. (Through his agent, Malloy declined to speak with Atlas Obscura for this story.) He promises they will be suitably gross and granular—and partly illustrated by puppets. For the reading, he says, the cast would “skip the boring stuff.”

“That’s too bad,” Reidenberg mumbles. She’s into the nitty-gritty details; this is a woman who once used spermaceti to grease some knives before sharpening them. However, many of the plot-driven songs that were performed were still stuffed with details about whales.

One song draws on chapter 133, “The Chase—First Day,” to describe the sight of Moby Dick when the whale is still deep underwater. The cast sings about “a white living spot no bigger than a white weasel.” Reidenberg says that sort of checks out: She’s spotted the white of a humpback’s flipper when it is still deep down, and says “animals that have white markings, on a sunny day, in relatively calm waters, can be seen pretty deeply.” But the description then takes a fanciful detour. The book passage goes on to describe the shape “magnifying as it rose, till it turned, and then there were plainly revealed two long crooked rows of white, glistening teeth, floating up from the undiscoverable bottom.” Sperm whales have been known to slam into ships—it’s even been somewhat controversially theorized that their blocky heads might have evolved as battering rams—but Reidenberg says a sperm whale probably wouldn’t charge with its mouth open. “I think that’s a little bit of fantasy,” she says. “I wouldn’t expect to see teeth.” Sperm whales only opens their mouths to feed when they’re hunting underwater, she says. Melville’s description of the whale’s “glittering mouth …. beneath the boat like an open-doored marble tomb” raises the stakes and danger of the encounter. Even with a closed mouth, the danger was real. Whalers “were slaying dragons, when you think about,” Reidenberg says.

In another song, “The Quarter-Deck,” which is based on chapter 36, Ahab gets amped up describing Moby Dick’s distinctive blow. The crew sings about a “bushy spout,” which the novel also likens to a “white cloud” and “a whole shock of wheat,” and Ahab badgers his men to keep an eye out. Reidenberg says that’s not bad advice—different species have different styles of spouts. “Blue whales have relatively tall, straight, smokestack-like spouting; humpback whales have a sort of Valentine-heart shape to the spouts; right whales have a very V-shaped [one]; and sperm whales have an asymmetric blow,” she says. While baleen whales have two nostrils as blowholes, toothed whales, including sperm whales, have just one (Moby Dick’s spout would have been on the left side of his head, and angled a little forward). “When you see a whale off at a distance, you’re going to be able to spot exactly which species it is,” Reidenberg says, but studying the shape of the exhalation wouldn’t help identify a particular individual. Unless Moby Dick had been the only sperm whale in that part of the ocean, there would have been no way to know for sure that the off-kilter plume was his.

But another detail in the song offers a more useful a hint about how to properly identify a whale—by studying the flukes, or the lobes that make up a whale’s tail. Ahab tells the crew to keep watch for a whale with “three holes punctured in his starboard fluke.” That makes sense to Reidenberg. “To have a marking that identifies this whale as an individual whale is very realistic,” she says. “These are used almost like fingerprints to identify individuals.” It would be conceivable, she adds, that a fluke could be punctured just as the story and performance describe if another toothed whale, maybe an orca, had bitten down on it.

The cast also sang a jolly, jovial tune about extracting the spermaceti, based on chapter 94, “A Squeeze of the Hand.” In the book, Ishmael describes plunging his hands into the oil; in the production, the cast chimes in with a hearty refrain of “Squeeze! Squeeze! Squeeze! All the morning long.” (“I thought they were talking about masturbation,” Reidenberg says.) Both the song and the book note that the globules in the spermaceti have the “smell of spring violets.” Wait—the gunk inside a sperm whale’s head smells like a bouquet? It’s hard to say: Some historic candlers seem to have prized the material precisely because it didn’t smell like much of anything, unlike tallow, for example. Reidenberg, for her part, isn’t sure exactly what fresh spermaceti smells like either—every whale she gets a look inside of is long dead and reeking. “If it was violets,” she laughed, “it would be pretty faint and pale in the distance compared to the rotting flesh around us.”

The production is affectionate toward the original text, but riffs on it, too. It’s adapted to make it feel grounded in 2019—with everything from references to subways, to grappling with racial inequality, to mulling over whether God is cisgender. It also talks about the ocean in a way that would never have occurred to Melville, because a lot has changed since 1851. The whaling industry is belly-up in America—if revived in Japan—and the waters themselves have changed, too—more acidic, warmer, polluted by industry. “These animals are swimming in what we have turned into a toilet,” Reidenberg says. The oceans are particularly deviled and befouled with nurdles, lines, and other little pieces of plastic.

Malloy’s adaptation is a product of now, and seems to imply that there’s no way to sing about the ocean in the 21st century without grappling with garbage. In a song called “Whalesong Interlude II,” the harpooners Tashtego and Daggoo sing long, low, and slow—exaggerated and muffled so they sound a bit like blue whales off in the distance. They serenade plankton and krill and lament the plot of “plastic trash in the Pacific” twice as big as Texas. “Will it all be ok?” they ask. They offer an answer, sad and sure: “It won’t.”

When the performance ends, Reidenberg and I sit in front of some walruses and chat. It was ambitious and wacky—a little serious, fairly goofy, and unmoored in time. It would be impossible to fit every detail of the novel into a musical—marathon readings are known to stretch across several days—but it was weird and wonderful to hear some of familiar ones put to a tune. Reidenberg thought that some of them carry important messages, too. “It was nice that they put something in there that was an environmental-awareness issue,” Reidenberg says. “I thought that was great.” She’s worried about the trash-strewn waters, and believes whales are great ambassadors for what’s at stake. “Everybody loves the whales—before, they used to be afraid of them,” she says. “They’ve gone from dragons to unicorns.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook