The Forgotten Fruit That Looks Like an Anus

Medlars’ shapes once inspired a lot of jokes.

Chances are, you’ve never eaten a medlar. Hundreds of years ago, though, medlars were a favorite fruit across Europe. The small, apple-like fruits were eaten raw by squeezing out their pulp, or made into desserts, often a firm jelly called “medlar cheese.” Unlike other fruits, it was ready in the winter, making it a popular treat and a welcome source of sweetness at a time when sugar was rare.

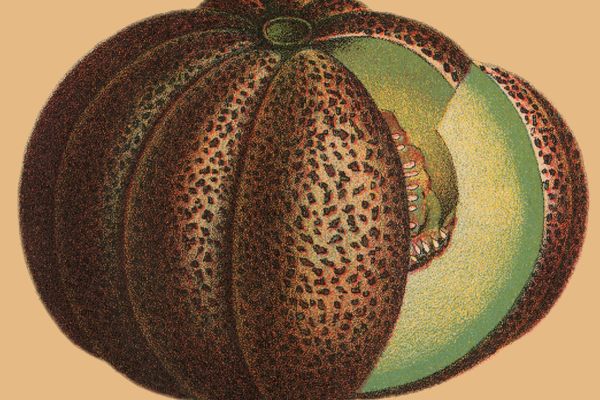

Despite their tasty, cinnamon-applesauce flavor and texture, medlars are best known for their shape. Both medieval and Renaissance writers fixated on the small fruit’s puckered ends. In England, they were called “open-arses” and “cat-arses,” while the French, thinking they seemed more canine, called them cul-de-chien. In other words, people thought the fruit looked just like an anus.

Chaucer referenced the fruit, and so did Shakespeare—in several of his plays, the fruit becomes a graphic metaphor. In Romeo and Juliet, one character jokes to another that Romeo probably fantasized about Rosaline (Juliet’s predecessor) as a medlar and himself as a “poperin pear,” which looked like male genitalia.

The rest of the medlar tree is inoffensive enough, and even beautiful, with spectacular white flowers in the spring and golden leaves in the fall. The fruits originated in the Middle East, and Romans spread the fruit across Europe. Writers and artists from Cervantes to Caravaggio depicted the fruit, which even made an appearance woven into the cloth of the mysterious Unicorn Tapestries.

So why did the ubiquitous medlar fall out of favor? For one thing, medlars aren’t “fast fruit.” Like certain types of persimmons, even mature medlars are too hard and sour to eat. A lengthy softening process, called “bletting,” is a prerequisite to enjoying them.

Bletting involves leaving medlars outside to frost over in the cold or burying them in sawdust or hay. Over two or more weeks, the fruit becomes soft and pulpy, and much sweeter. The skin wrinkles, and the fruit’s interior turns from white into a rotten-looking brown. Then, the pulp can be eaten as-is, or made into jelly or desserts. One cookbook from the 16th century describes how “rotten” medlars, mixed with egg yolks, ginger, and cinnamon, can be turned into a tasty pie.

Next to gleaming apples and perfect bananas, mushy brown medlars have become the ugly duckling of the fruit bowl. Even so, for the last few years, chefs and gardeners have shown interest in the medlar as a lost delicacy. But you may have to go on a quest to find one—or plant a medlar tree yourself.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook