The Artful Imperfection of Medieval Manuscript Repair

Old parchment is full of creative fixes.

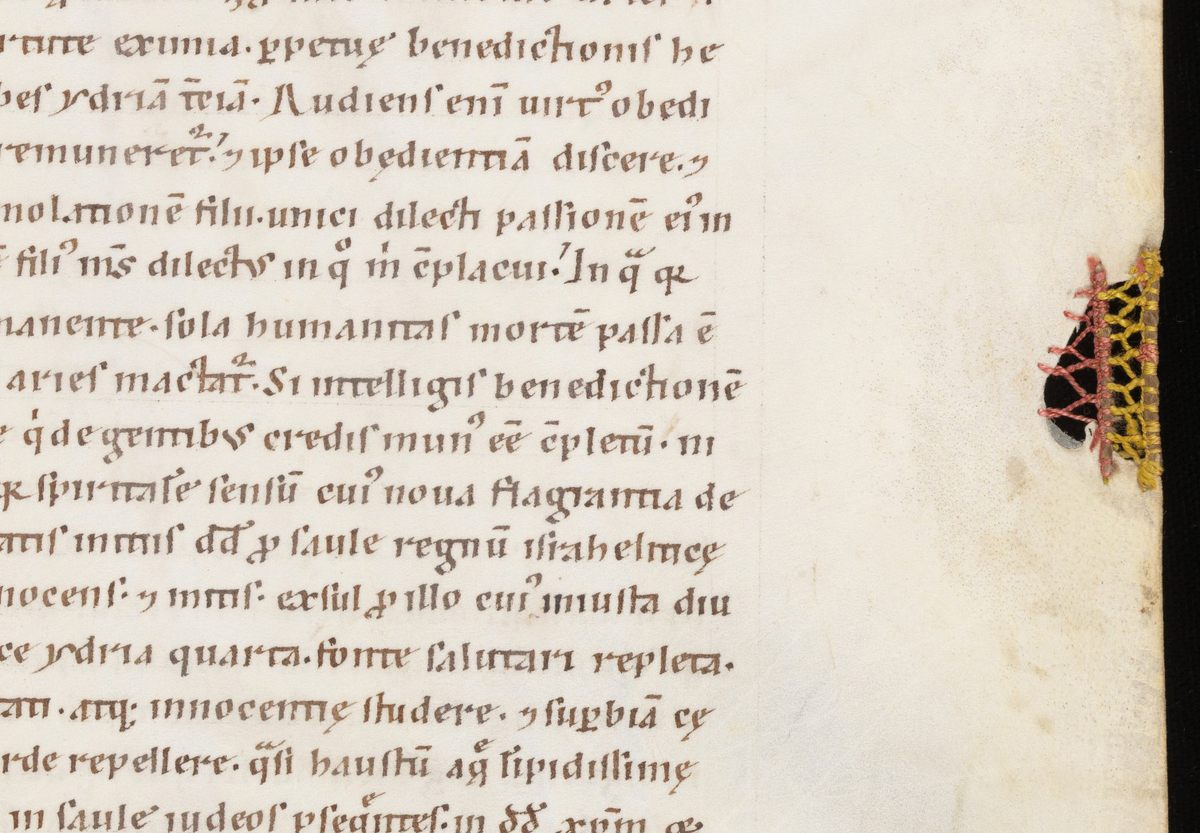

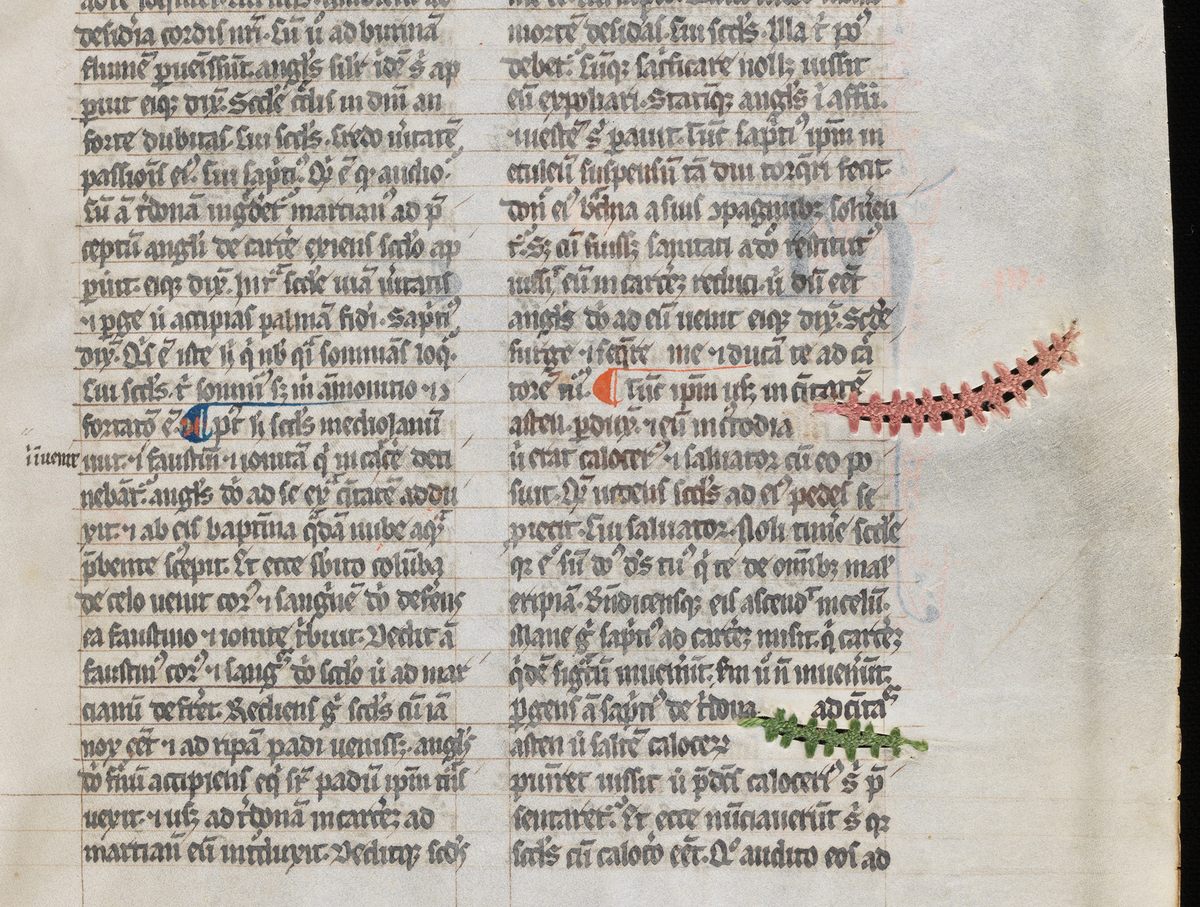

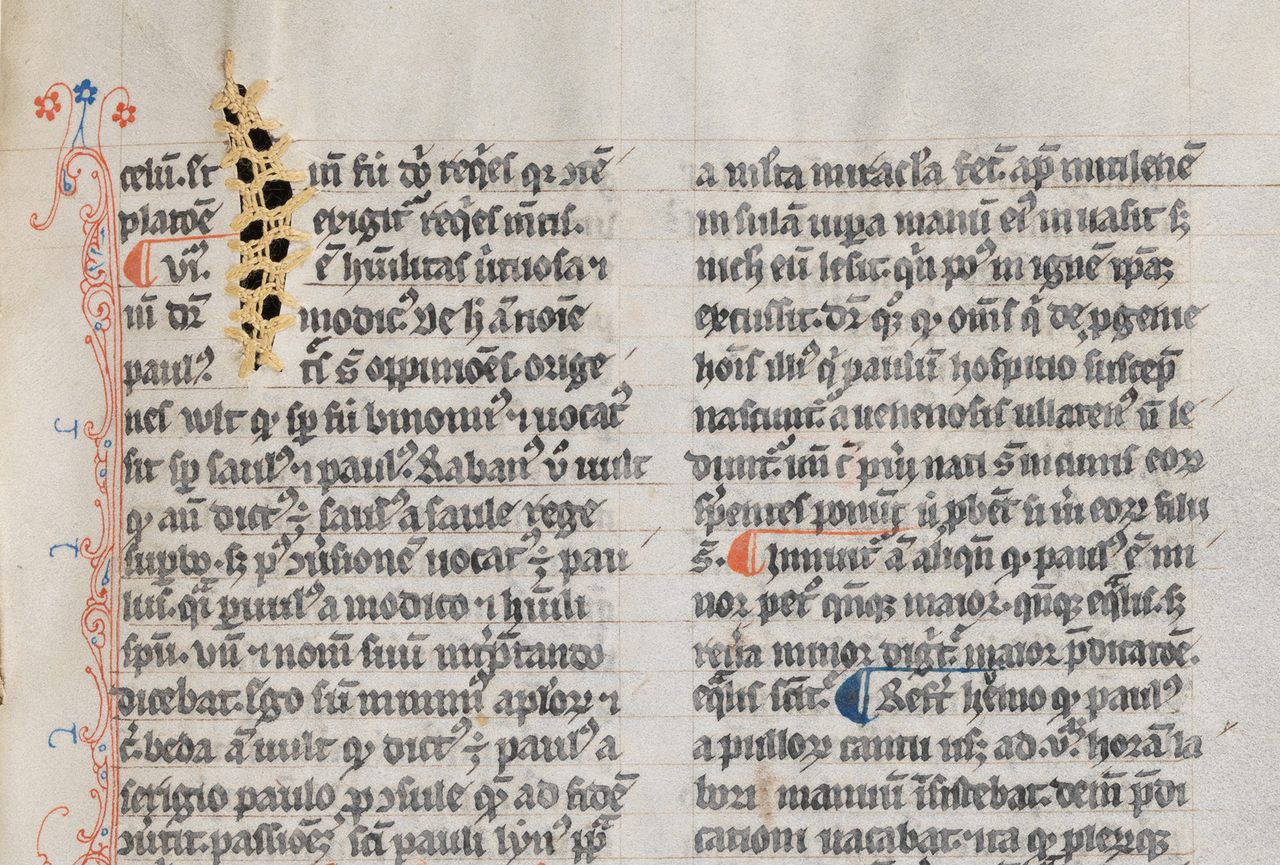

In the Cantonal and University Library in the ancient city of Fribourg, Switzerland, is a 14th-century manuscript with some gloriously beautiful defects. Scattered throughout the text are small tears and holes. And many of them have been carefully, intricately stitched together with colorful thread.

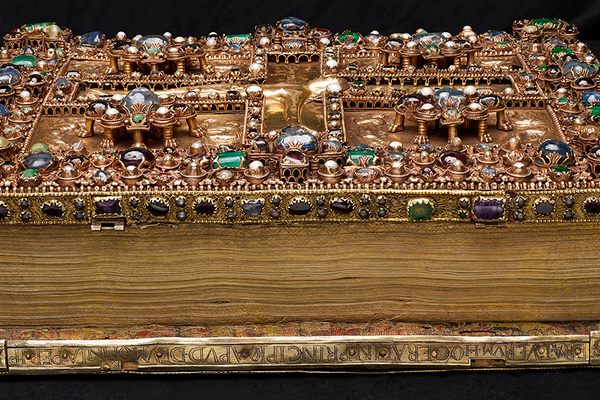

Medieval manuscripts have all sorts of interesting quirks, from strange marginalia to dazzling jeweled bindings, and the basis of most of these books, parchment, has its own story. Parchment is created by soaking an animal skin—usually sheep, goat, or calf—in a lime solution and then stretching it onto a wooden frame. The parchment maker then repeatedly scrapes the skin with a curved knife to remove any flesh or hair until the skin is suitably taut, thin and smooth. It is a lengthy process, and has always been susceptible to mistakes and natural imperfections.

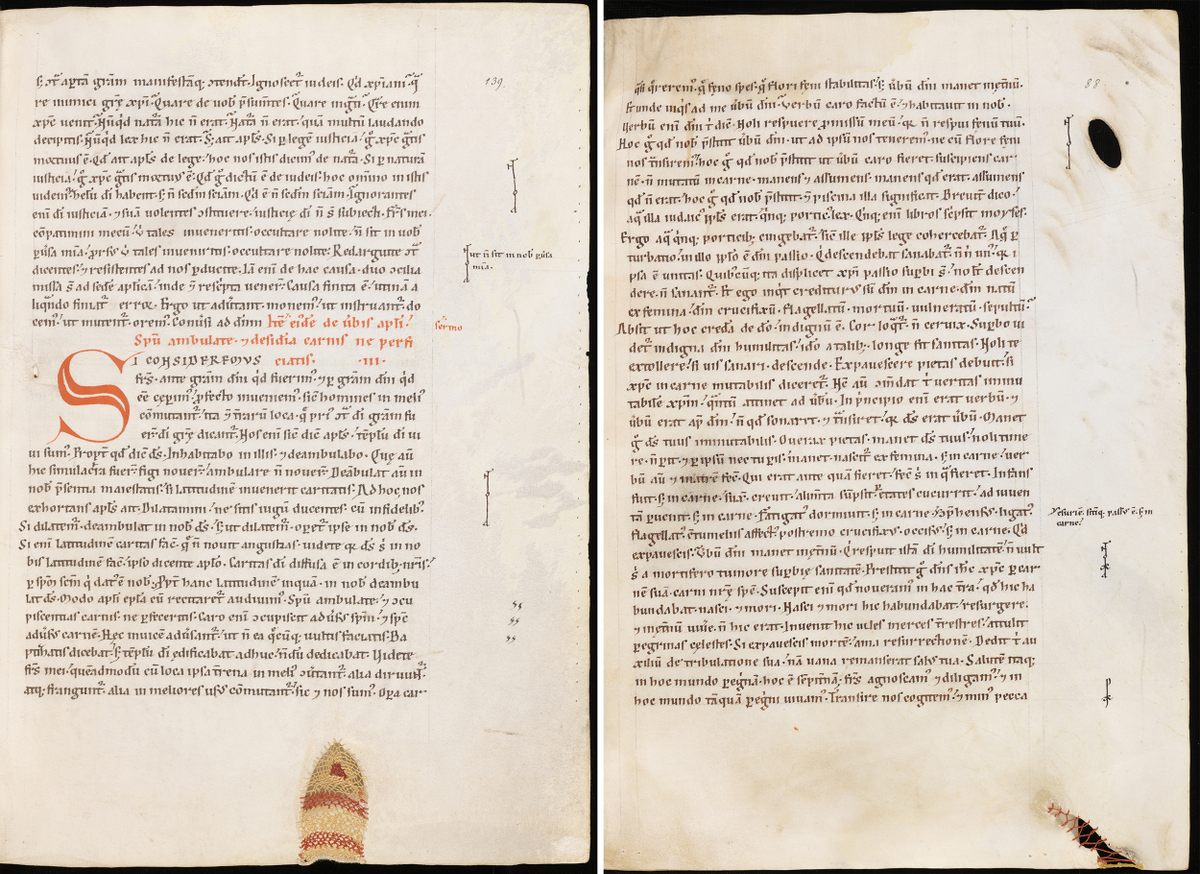

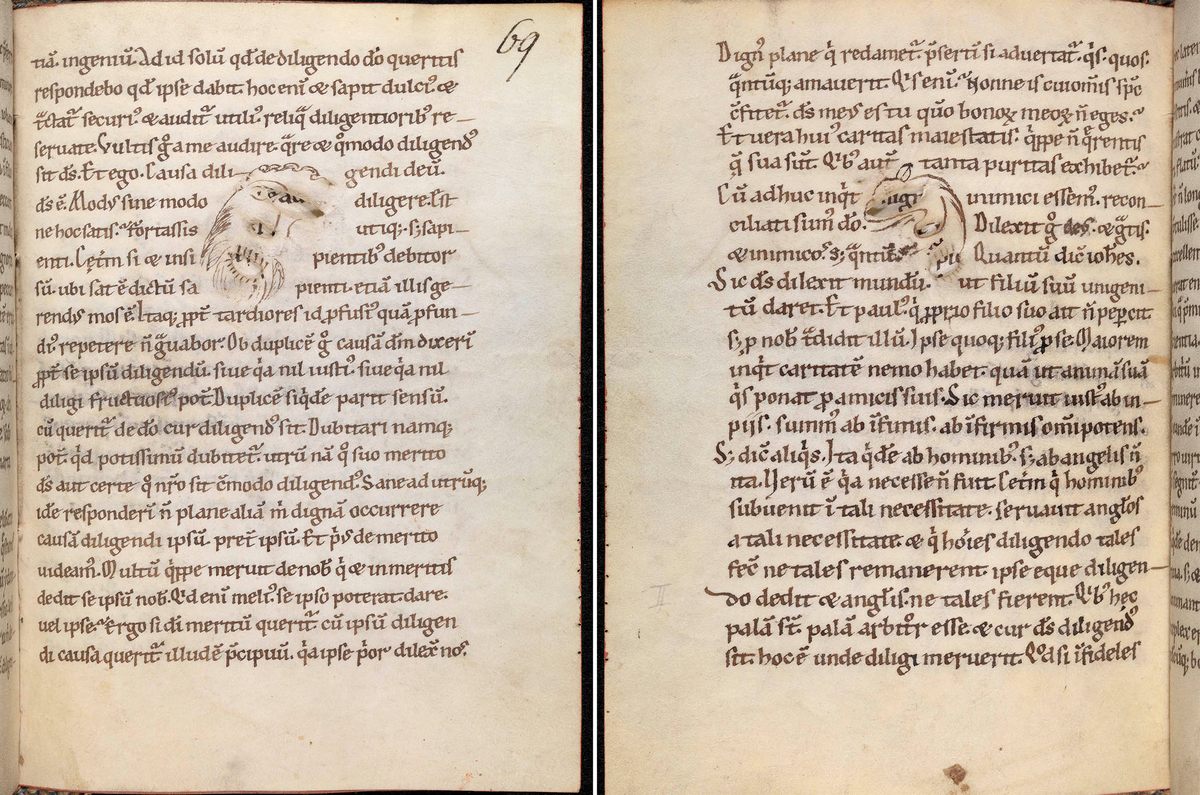

“Any sort of defect in the skin itself will open up into a hole because you’re stretching the skin,” says Christine Sciacca, Associate Curator of European Art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. In addition, stretched skin has “an irregular perimeter, so you’re trying to transform an irregularly shaped piece of animal skin into a rectangular book form,” she explains. The parchment could also be damaged by the scraping. Holes in the parchment weren’t always dealt with, but when they were, any repairs needed to be done before it could be written on. This might include both patching over holes and evening out edges, explains Sciacca. The repair method could be crude or rudimentary—“Frankenstein” repairs, as Sciacca jokingly calls them—but, as writer Paul Cooper recently highlighted, sometimes they could be quite beautiful.

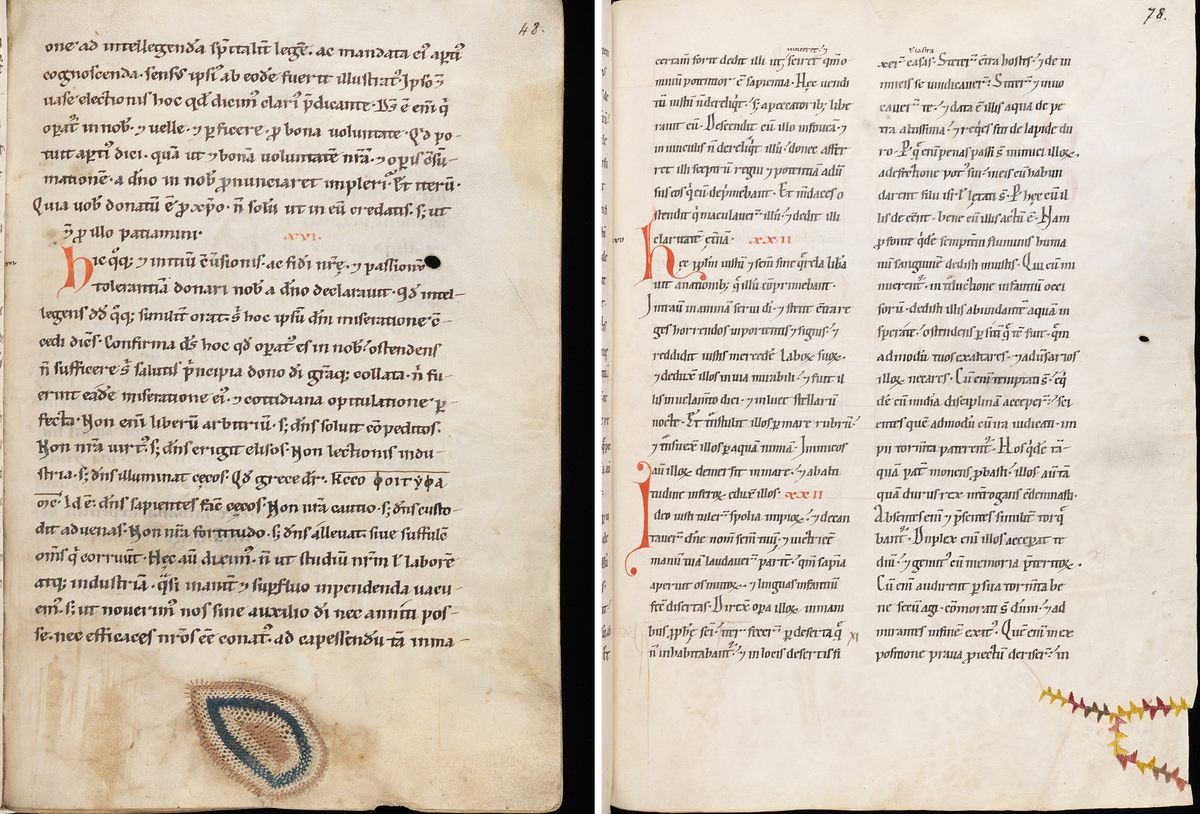

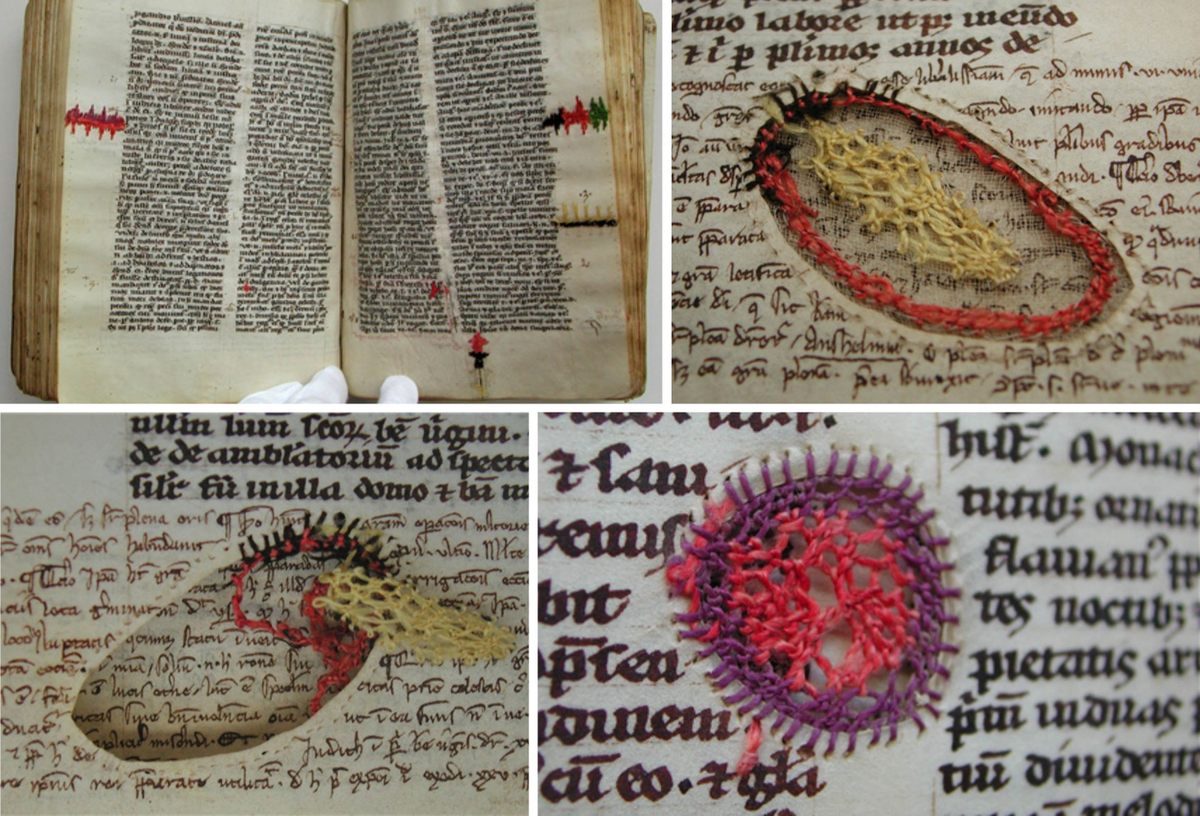

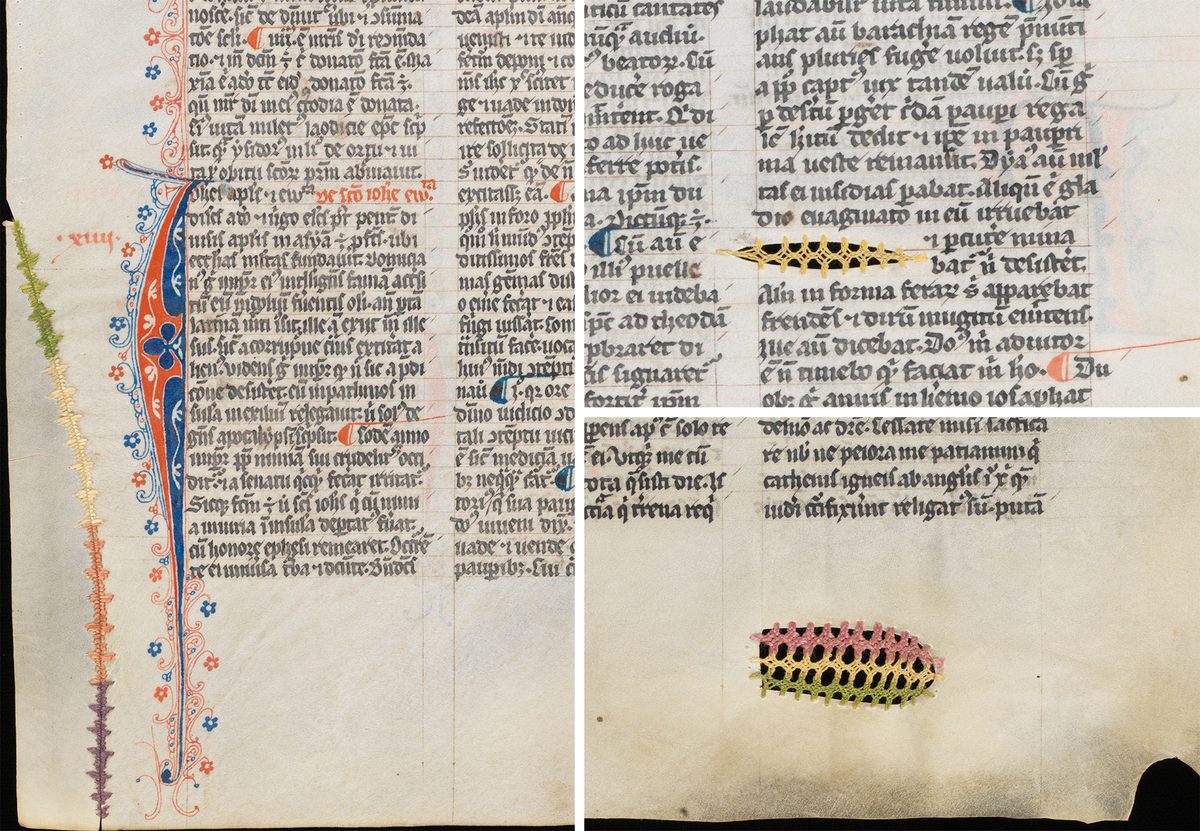

In that same 14th-century text in Fribourg, a single page is elegantly adorned with two sets of thin stitches, one pink, one green. Elsewhere in the same manuscript there are rainbow-hued repairs of different shapes and sizes. In a text held at the Engelberg Abbey library in Switzerland, stitches at the edge of the page create a “rope”, as Sciacca refers to it, to fill in the edge of the parchment. And from the same library, the missing side of one page has been patched with an additional square of parchment.

As medieval book historian Erik Kwakkel points out, these repairs must have been common in certain monasteries. “Where I was finding a lot of these embellishments were in manuscripts that came from either nunneries, or from what they call in Germany, double cloisters,” Sciacca says. “So you have this paired male and female monastic community. They live separately, but they’re allied with each other, and they’re physically located next to each other. So it seems that this may be part of what was, in fact, women’s training, what was nuns’ training, which was to practice embroidery. And they were doing it not just on textiles, but also actually in manuscripts.”

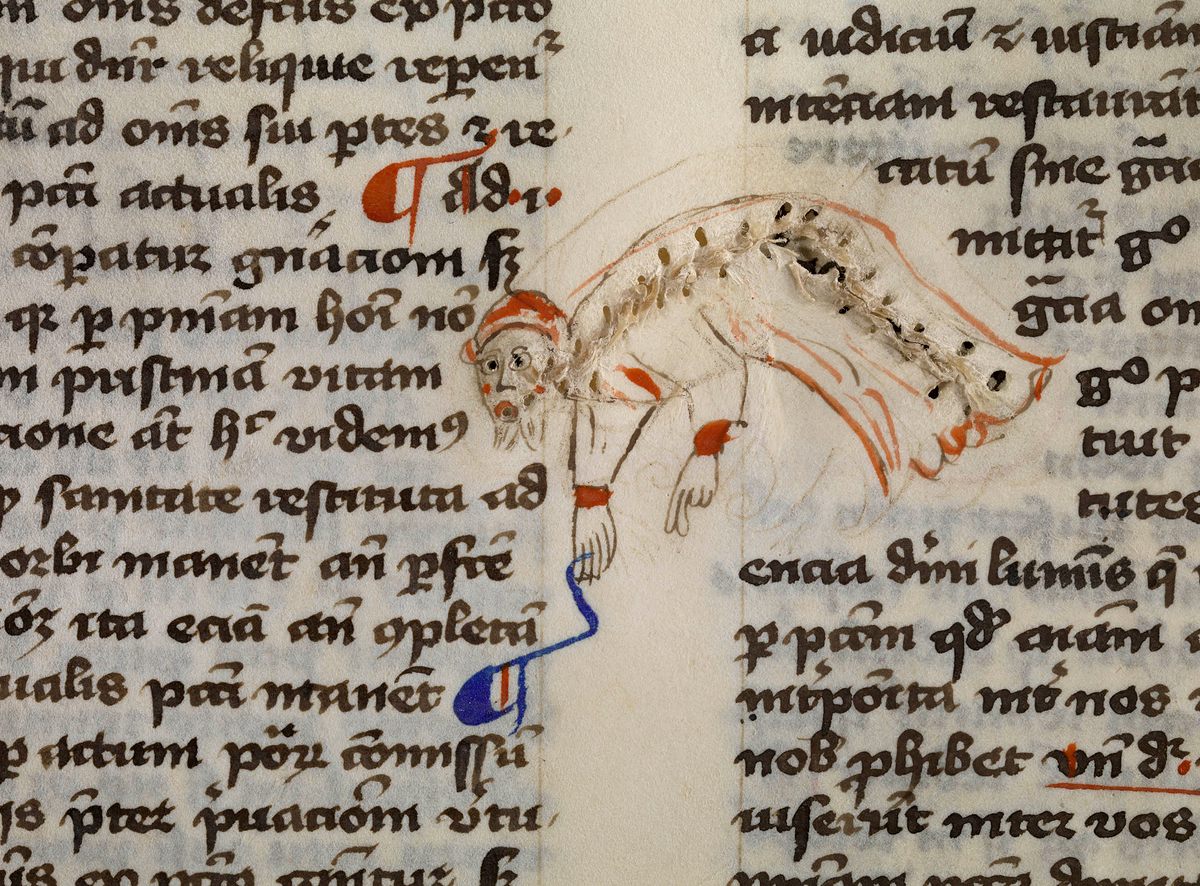

Stitching wasn’t the only way to make the best of flawed parchment. There are instances of holes being incorporated into illustrations, or used to reveal an illustration on the following page. The stitches themselves could even be embellished. In a text in Germany’s Bamberg State Library, a curve of plain-colored stitching is surrounded with the drawing of a man so that the thread resembles his skeleton.

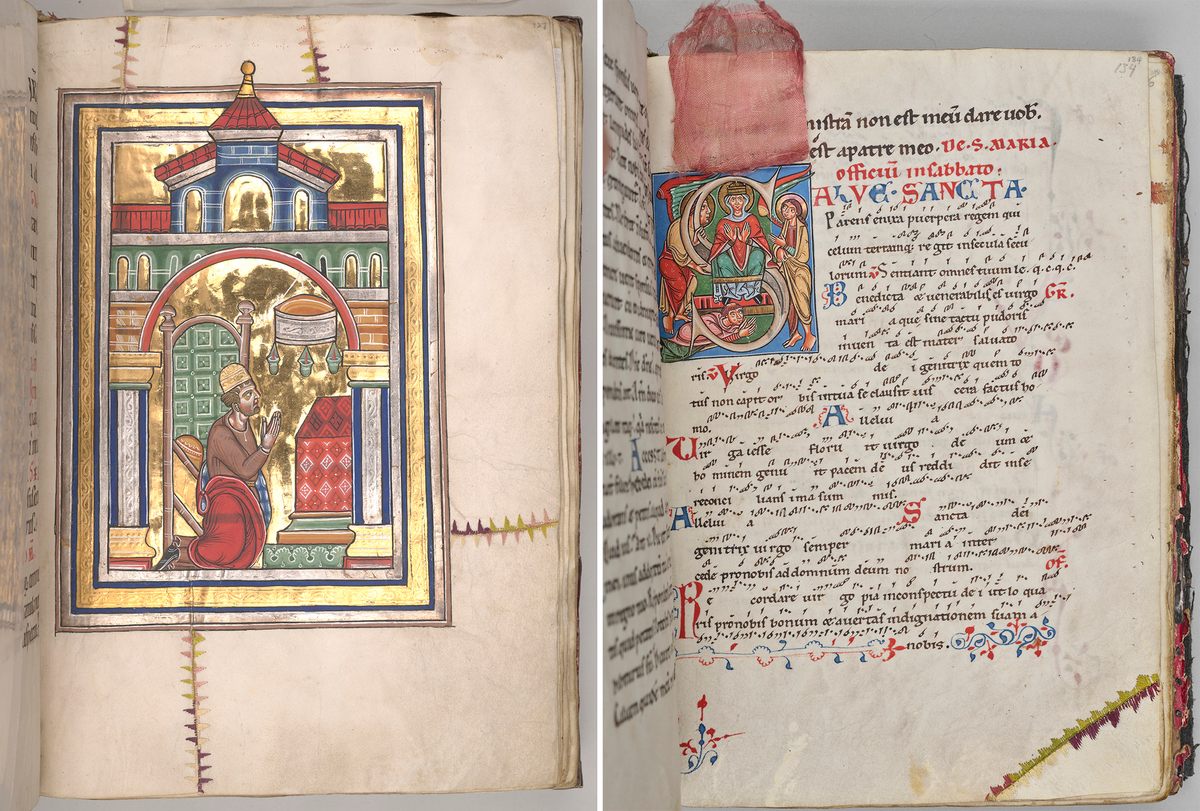

Embroidered repairs weren’t the only use of textiles in medieval manuscripts—or even the only use of textiles on a single page. In a 13th-century text held at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, a silk flap obscures an illuminated letter, while the bottom corner of the same page has been repaired with thread. Sciacca says this type of embellishment—curtains, she calls them—was mainly used in liturgical texts, and added an extra element to a priest’s reading. “It’s a very performative thing,” says Sciacca. Sometimes they were placed over more disturbing imagery—depicting the Apocalypse, for example—to add weight and meaning for the viewer.

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images of these beautifully flawed manuscripts.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook