Electroshock Machines and Einstein’s Brain: Inside 3 Macabre Medical Museums

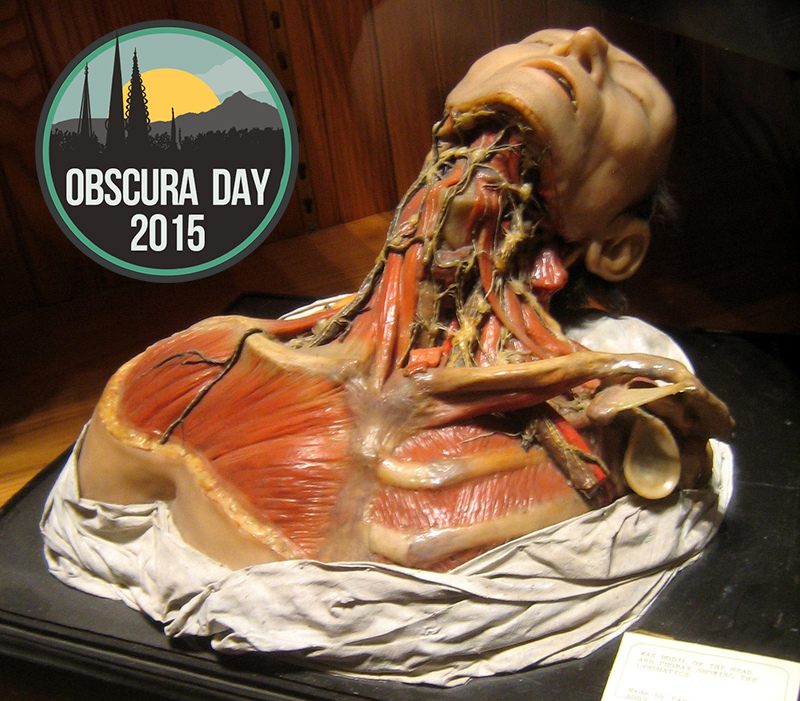

An anatomical model at the Mütter. (Photo: istolethetv/Flickr)

Some people like to spend their weekends windsurfing. Others prefer to examine bits of brains, peer into jars stuffed with deformed body parts, or look at rusty surgical tools from the pre-anesthetic era. If you are among the ranks of the latter, there are three medical facilities in the U.S. particularly worthy of your attention.

Here’s what to look out for at Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum, Indianapolis’ Indiana Medical History Museum, and Boston’s Ether Dome on Obscura Day 2015.

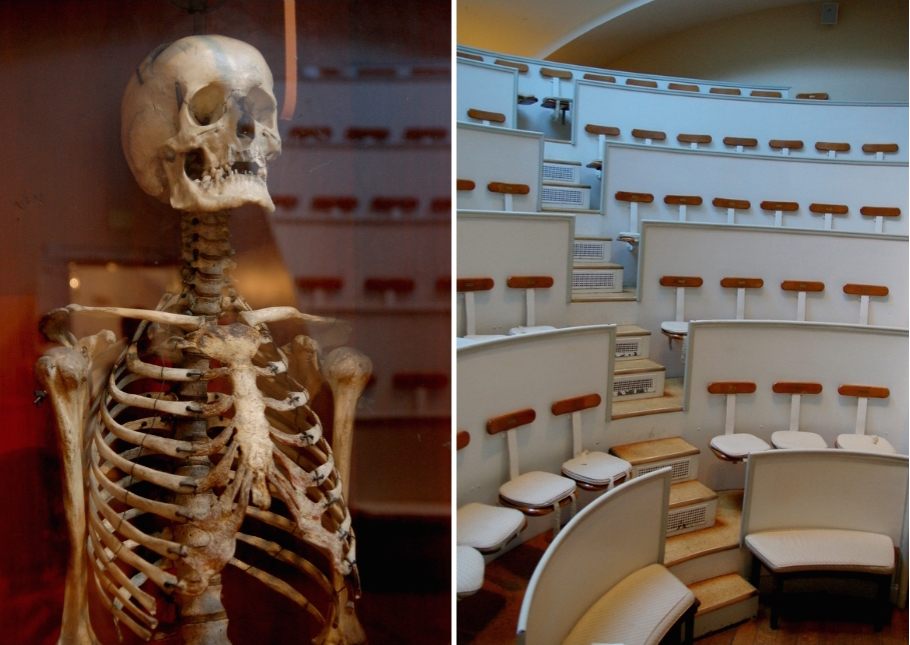

Skeleton and stadium seating at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Ether Dome. (Photos: Michelle Enemark)

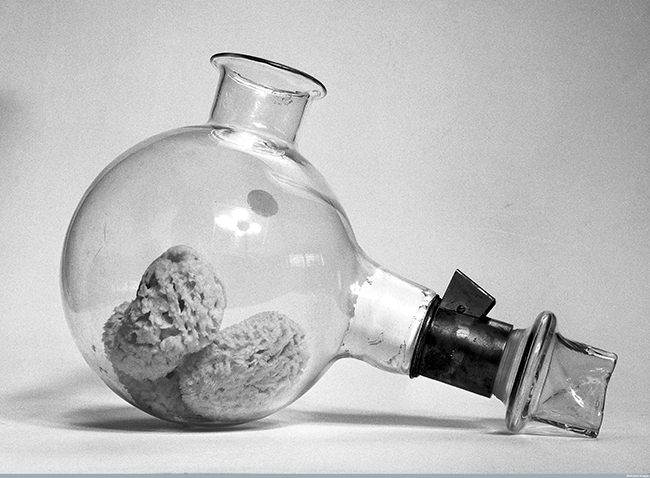

The circular, 19th-century operating theater at the top of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Bullfinch building is known as the Ether Dome. It was here that, on October 16, 1846, dentist William Morton performed the first public demonstration of a new anesthetic by administering vapors of diethyl ether to Edward Gilbert Abbott, a patient with a massive tumor jutting out the side of his neck.

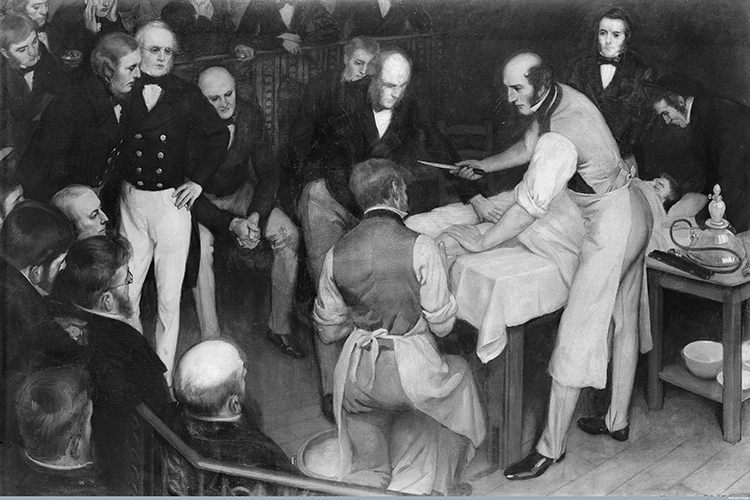

At the time, ether was an option for recreational drug use (“ether frolics”), but wasn’t being used for its numbing properties during medical operations. Instead, patients needing surgery would prep for the procedure by drinking a whole lot of whiskey, taking a mallet to the head, or ingesting enough opium to make the ensuing pain more bearable. Surgeons were vaunted not for their precision, but for their speed—top Scottish doctor Robert Liston was famed for his ability to lop off a limb in under three minutes. (There was occasional collateral damage involved in this swiftness, such as the time Liston accidentally cut off a patient’s testicles when amputating his leg.)

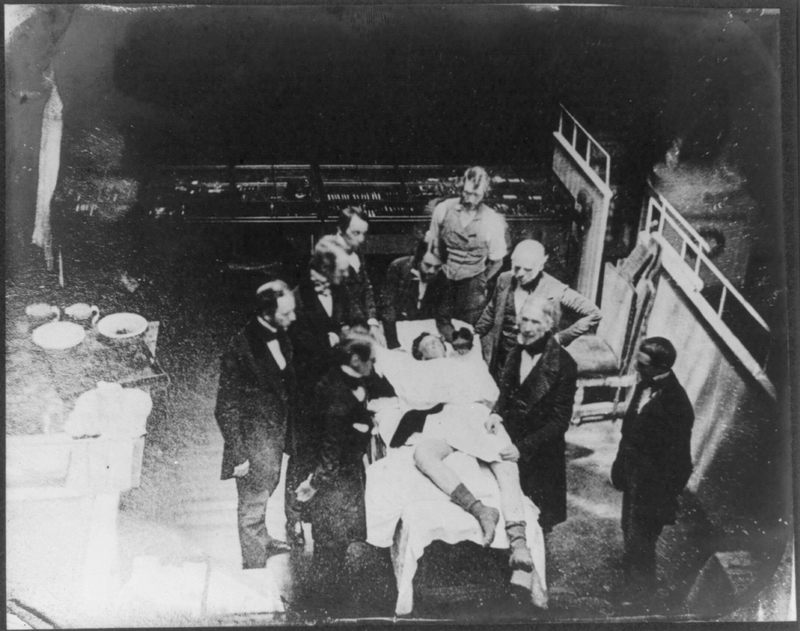

Robert Liston operating on a patient (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

Robert Liston operating on a patient (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

On that day in the Ether Dome in 1846, dentist/anesthetist Morton and surgeon John Warren were just hoping to get through the operation without any wailing or gnashing of teeth from their patient. A crowd of curious onlookers peered down from the stadium seating as Warren sliced into the tumor on the unconscious and unresponsive Abbott’s neck. When Abbott awoke and confirmed he had felt nothing, a triumphant Warren turned to his audience. “Gentlemen,” he said, “this is no humbug!”

A replica of Morton’s Ether Inhaler (Photo: Wellcome Images, London)

On Obscura Day you can stand on the very spot where Abbott’s tumor was painlessly removed. You can also meet someone who was in the audience on that fateful day: Padihershef, a mummified stonecutter from Thebes. The Egyptian mummy, who died circa the sixth century BC, was gifted to Mass General in 1823 and has been watching over the Ether Dome ever since.

A re-enactment of the 1846 demonstration of ether as an anesthetic. (Photo: Library of Congress)

A re-enactment of the 1846 demonstration of ether as an anesthetic. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Indiana Medical History Museum, Indianapolis

The teaching amphitheater at IMHM. (Photo: Jbryan317/Wikipedia)

Located in the Old Pathology Building of now-closed Central State Hospital—which was known in the 19th century as the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane—the Indiana Medical History Museum is the oldest surviving pathology facility in the United States.

The museum’s collection of 19th-century surgical tools is enough to induce light-headedness in those who possess a more active imagination. Civil War-era amputation kits, surgery sets from a time before hand-washing was standard, and barbaric-looking blood-letting devices paint are all very handy for making visitors appreciate the innovations of 21st-century medicine.

The hospital’s clinical laboratories, teaching amphitheater, and autopsy room have all been preserved to reflect their original 1890s state. On Obscura Day, gather in the amphitheater for a special presentation of items from the museum’s collection. Prepare yourself for human remains and an electroshock machine.

The IMHM chemical laboratory. (Photo: Jbryan317/Wikipedia)

It’s easy to be overwhelmed at the Mütter Museum: though it has a modest square footage, the shelves are crammed with rows of human skulls, jars of floating fetuses with birth defects, and lifelike wax models of dermatological conditions. Then there is the Soap Lady, her face captured in eternal, silent scream. And you can’t look away from the melting skeleton, or the replica of a nine-foot-long distended colon packed with 40 pounds of fecal matter.

Given all of these striking sights, some visitors bypass the museum’s nooks and crannies, where small treasures await discovery. Take, for example, the Chevalier Jackson Collection. Secreted away in columns of drawers are thousands of foreign objects that Dr. Chevalier Jackson, a pioneering Philadelphia otolaryngologist, extracted from people’s throats, esophaguses, and lungs during his near-75-year medical career. Neatly arranged into categories, the items range from coins to buttons, bones, nuts, and even small toys.

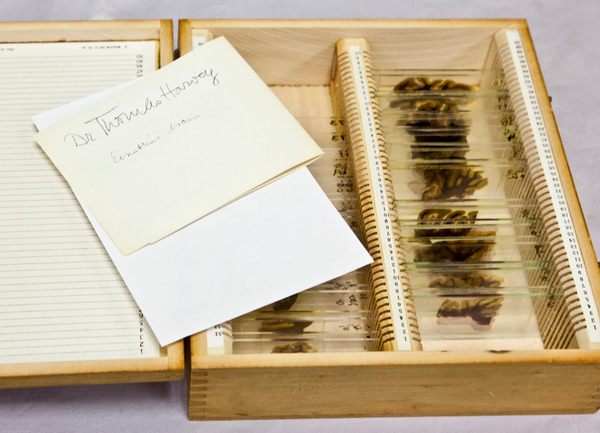

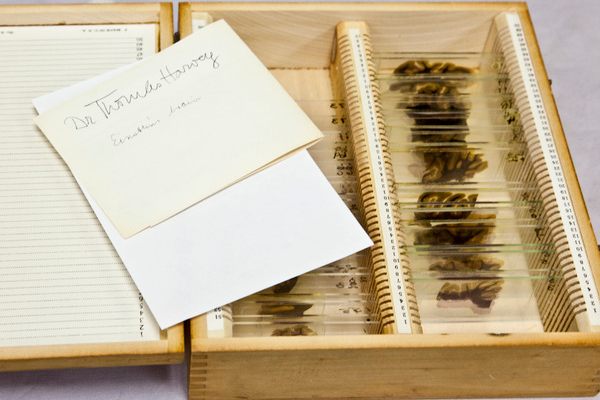

Another exhibit that is easy to miss is the display featuring pieces of Einstein’s brain. When Einstein died in 1955, the New Jersey pathologist who performed the autopsy, Dr. Thomas Harvey, removed the brain without the family’s permission. When Einstein’s relatives learned what had happened, they allowed Harvey to keep the brain on the condition that it be used for scientific research only. Einstein’s brain sat in a glass jar for decades, until Harvey eventually dissected it into 240 pieces and created 1,000 tissue slides. A selection of those slides is now on view at the Mütter Museum, which is hosting a behind-the scenes “wet and dry” specimen-viewing session for Obscura Day.

Slides of Einstein’s brain. (Photo: Courtesy of the Mütter Museum, used with permission)

What is Obscura Day? It’s more than 150 events in 39 states and 25 countries, all on a single day, and all designed to celebrate the world’s most curious and awe-inspiring places. To get ticket information on events at the Mütter Museum, Indiana Medical History Museum, and the Ether Dome on Obscura Day, go here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook