The Early Gay Rights Manifesto That Lord Byron (Probably) Didn’t Write

In the 19th century, the poem “Don Leon” argued for British Parliament to drop the death penalty for homosexuality.

In the early 1820s, a document entitled “A Free Examination into the Penal Statutes” circulated throughout the British Parliament. Though its complete contents are now lost, excerpts show that it argued for something remarkable: a softening of punishments against men who had sexual relationships with other men.

In England, intercourse between men had been punishable by death since King Henry VIII’s Buggery Act of 1533. (Intercourse between women was not acknowledged.) But elsewhere in Europe, that was changing. Around the turn of the century, Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Tuscany had abandoned capital punishment for homosexuality; France, meanwhile, decriminalized it entirely.

Of course, as historian Charles Upchurch writes in Queer Difficulty in Art and Poetry, “elimination of the death penalty was less a sign of greater tolerance for these acts than an attempt to better align the severity of the punishment with the nature of the infraction.” But the changing tides forced the British Parliament to re-examine its position, and in 1819, it created the Committee of Inquiry Into the State of Criminal Law to evaluate its use of the death penalty.

“A Free Examination into the Penal Statutes” appeared soon after, but its plea for leniency in punishing homosexuality did not sway members of Parliament. The Buggery Act remained on the books. But the document had, for the first time in centuries, opened up debate on the topic.

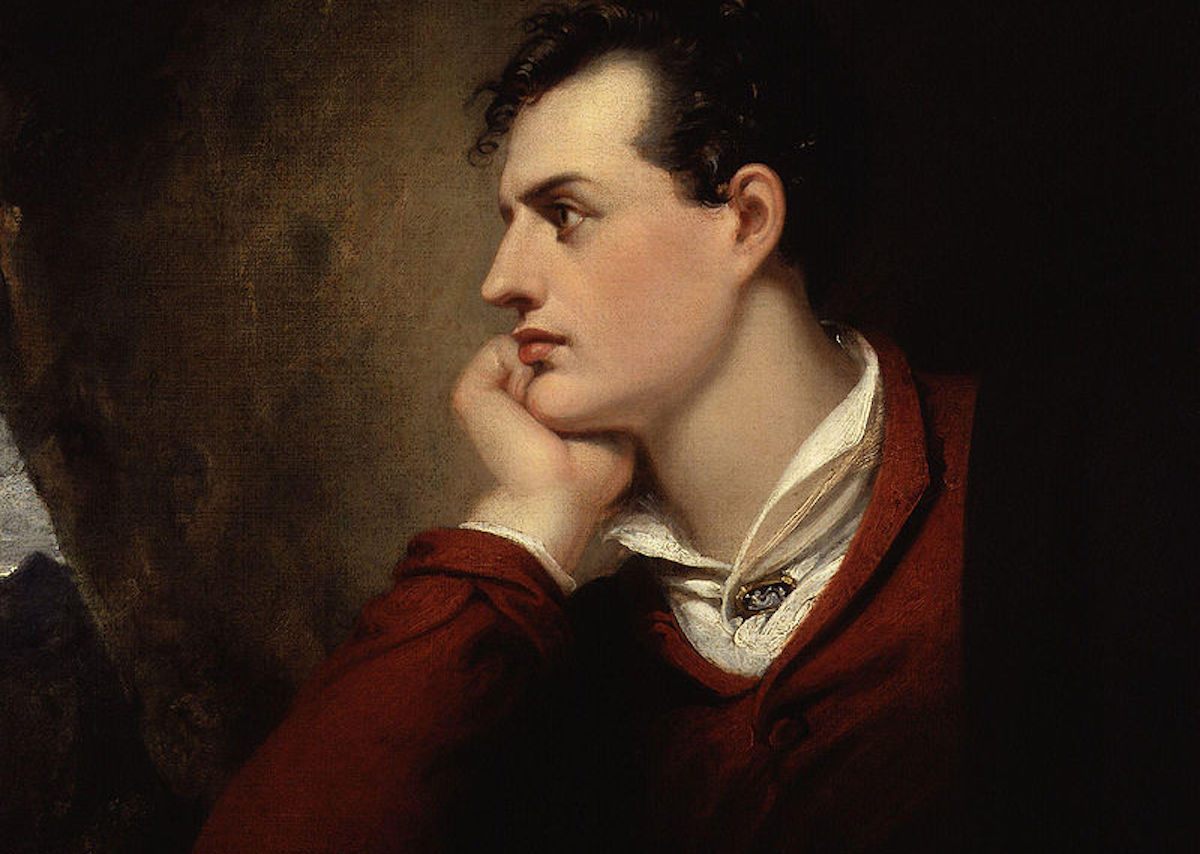

Enter Lord Byron.

Well, sort of.

The famed poet had a long history of affairs with men and women, though for much of his life, few knew. The Guardian recounts how, when a former lover began spreading rumors that he had engaged in intercourse with other men, his world imploded. He wrote, “I was advised not to go to the theatres, lest I should be hissed, nor to my duty in parliament, lest I should be insulted.” Fearing for his life, he decided to flee his home country. In April 1816, he left England.

After Byron’s death in 1824, a group of his friends agreed to have his papers burned. But years later—long after “A Free Examination into the Penal Statutes” had fallen out of circulation—a poem attributed to Byron surfaced. It was entitled “Don Leon,” and its front page noted that it formed “Part of the Private Journal of His Lordship, Supposed to Have Been Entirely Destroyed.” (Its full contents can be read here.)

The poem—a sprawling manifesto of more than 50 pages—used Byron’s personal experiences to argue in favor of Parliament dropping the death penalty, making the then-radical claim that homosexuality was normal.

God, like the potter, when his clay is damp

Gives every man, in birth, a different stamp.

According to most modern scholars, Byron himself almost certainly did not write the poem. Its author attached Byron’s name to attract attention. But the poem’s accounts of Byron’s multiple love affairs appear to be accurate, suggesting that at least one of the authors was a close friend of Byron’s.

Its publication history, like its authorship, is murky. The first edition was written in the late 1820s or early 1830s—historians don’t agree.

The first record of the poem only appeared later, in 1853, when a person named “I.W.” wrote in the London journal Notes and Queries that he had seen a copy printed outside of Britain. In 1866, William Dugdale, a notorious salesman of pornographic books, re-published the title, apparently genuinely believing Byron to be its author. His edition first catapulted the poem into public prominence.

Fortune Press attempted to publish “Don Leon” again in 1934, but London police seized it on charges of obscenity and destroyed most copies. Even a century later, the poem’s claims about sexual equality alarmed many.

In fact, the author—posing as Byron—used “Don Leon” to excoriate supporters of punishments for homosexuality for their intolerance:

’Tis you that foster an illicit trade,

And warp us where a strict embargo’s laid.

‘Twere just as well to let the vessel glide

Resistless down the current, as confide

In charts, that lead the mariner astray,

And never mark the breakers in his way.

The poem goes on:

Thou ermined judge, pull off that sable cap!

What! Can’st thou lie, and take thy morning nap?

Peep thro’ the casement; see the gallows there:

Thy work hangs on it; could not mercy spare?

What had he done?

…What bonds had he of social safety broke?

Found’st thou the dagger hid beneath his cloak?

He stopped no lonely traveller on the road;

He burst no lock, he plundered no abode;

He never wronged the orphan of his own;

He stifled not the ravish’d maiden’s groan.

His secret haunts were hid from every soul,

Till thou did’st send thy myrmidons to prowl.

At points, “Don Leon” levels direct attacks on politicians who have previously endorsed harsh punishments for homosexuality. Referring to Colonel Richard Martin, who fought against animal cruelty but was supportive of the death penalty for gay men, the author decries, “Martin has mercy—yes, for beasts, not men.”

The author then turns to another politician, James Brogden:

And Brogden’s modesty his voice impedes,

Who, when the sections of the a bill he reads,

With furs of coneys, to a gentle hush

Subdues his tone, and feigns a maiden’s blush.

And to James Mackintosh, he asks: “But answer, Mackintosh; wert though asleep?”

Why gull the nation, with thy plans to mend

The penal code in speeches without end,

And, like a jelly bag, with open chops,

Dwindle and dwindle into drizzling drops?

But the emotional heart of the poem lies with its accounts of Byron’s romantic interests. The poem chronicles his early attraction to men and women, and his inability to act on those desires.

Thus passed my boyhood: and though proofs were none

What path my future course of life would run

Like sympathetic ink, if then unclear,

The test applied soon made the trace.

Ultimately, the poem did not immediately achieve its aims. Between 1806 and 1835, 56 men were killed for having sex with other men.

But even that was changing. In 1835, the last execution for sex between men took place. And in 1861, the death penalty for such acts was officially abolished, though it remained a crime worthy of imprisonment. “Don Leon” likely did not contribute to this shift, but it remains a significant piece of cultural history—proof of a LGBT resistance to oppression long before it was supposed to have existed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook