Letter-Writing Manuals Were the Self-Help Books of the 18th Century

Need to kindly but firmly chastise your son for buying a horse? Read the manual.

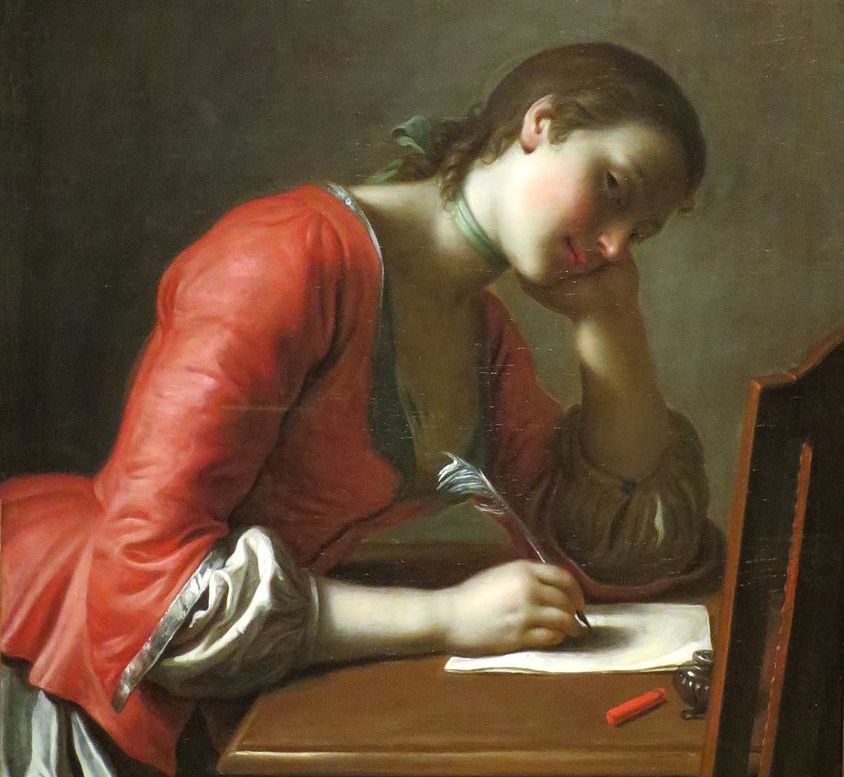

Detail from Young Girl Writing a Love Letter by Pietro Antonio Rotari (1755). (Image: Public Domain)

Let’s say a friend started dating someone who was clearly bad news. How might you tactfully convey your disapproval? In the 1740s, the answer was easy: you’d go to your bookshelf, pull out a thick tome entitled Letters Written to and for Particular Friends, and flip to sample letter number 145, entitled “To a young Lady, cautioning her against keeping Company with a Gentleman of bad Character.”

Like all human communication, exchanging handwritten notes is a confusing, anxiety-producing and socially fraught endeavor. And, at one time, it was a new technology. Letter-writing manuals had been around since the 1500s, but the 18th century was the golden age for these publications. At the time, there had lately emerged a form of written communication known as the “familiar letter,” which was characterized by informal, from-the-heart prose, rather than displays of intellect, reason, and wit.

Letters Written to and for Particular Friends, written by British novelist Samuel Richardson in 1741, was one of a slew of letter-writing manuals published in the mid-to-late 18th century. These thick volumes contained example letters suited to a wide range of specific occasions, from applying for a job to approaching the courtship of someone dreamy. The letters, penned from the perspective of fictional characters, were designed to be used as templates for those lacking confidence in their written expression skills.

This particular volume flourished because letter-writing, long the domain of the rich and well-educated, became more widespread and accessible. Members of the middle and working classes could now compose persuasive notes to friends, family members, potential paramours, and business prospects. But with many of these people lacking a formal education, they sought help on how to best adhere to current conventions.

This included, of course, form love letters.

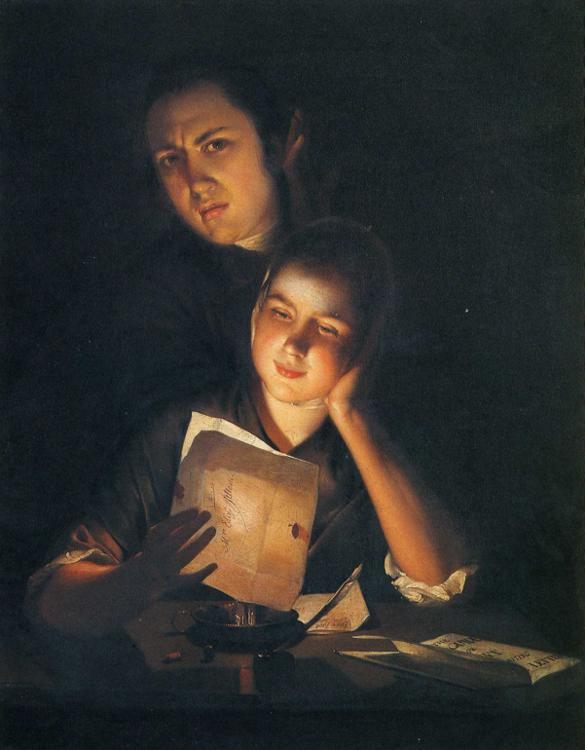

Joseph Wright’s Girl Reading a Letter by Candlelight, With a Young Man Peering over Her Shoulder (c. 1760). (Image: Public Domain)

The authors of letter-writing manuals offered grammar advice, etiquette tips, and social considerations to these new authors. One of the main focuses was on writing prose that came across as sincere and natural. “When you write to a friend, your letter should be a true picture of your heart, the style loose and irregular,” wrote H. W. Dilworth in his 1758 guide, The Familiar Letter Writer. “[T]he thoughts themselves should appear naked, and not dressed in the borrowed robes of rhetoric; for a friend will be more pleased with that part of a letter which flows from the heart, than with that which is more a product of the mind.”

The British Library calls 18th-century writing manuals “an early form of self-help book.” They certainly helped members of the middle class understand how to pen an endearing eloquent note, which could lead to a favorable courtship, a job offer, and a rise in social status. “By demystifying the rules and conventions of letter writing, a social practice traditionally symbolic of power, authors of familiar letter manuals helped middling families pursue their claims to social refinement and upward mobility,” writes Konstantin Dierks in The Familiar Letter and Social Refinement in America, 1750-1800.

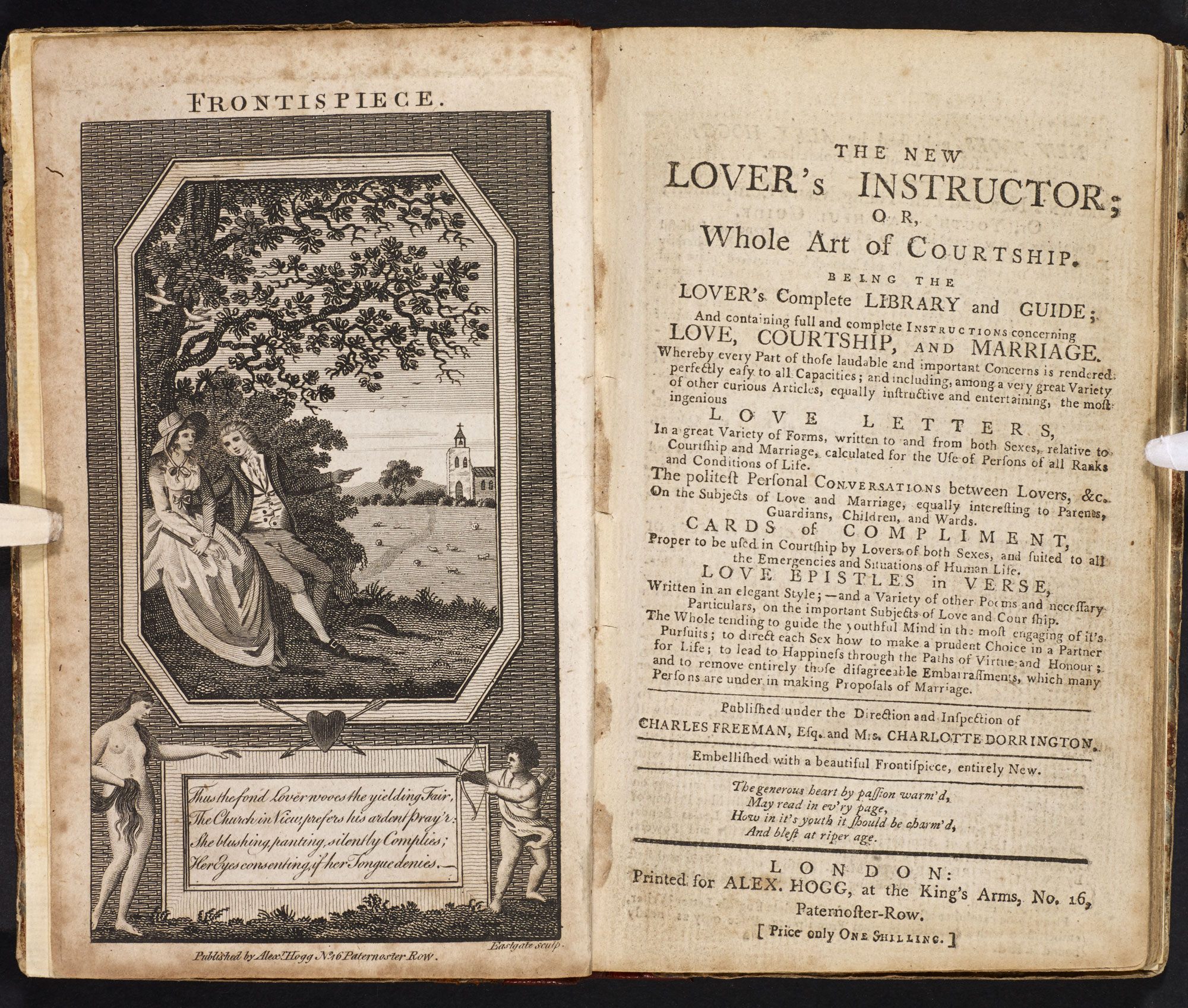

Success in love was another promise from the writers of letter manuals. The Lover’s New Instructor, a courtship-focused guide published circa 1780, provided a book full of sample letters to “serve as examples for giving a clear idea of the manner in which a correspondence should be maintained on the important points of Love and Marriage.” The authors assured its less-educated readers that those who, “through the various avocations of life, have been denied opportunities of attending to the forms of polite expression, may, by giving a grace and polish to their language, improve rusticity into good breeding.”

The frontispiece of The New Lover’s Instructor, a courtship-focused letter-writing guide published circa 1780. (Image: British Library/Public Domain)

As for what the letters in these manuals were like, a glance at the list of 173 sample letter titles in Letters Written to and for Particular Friends shows just how specific the writers got. Letter 70 is entitled “From a Father to a Daughter against a frothy, French Lover,” and includes the following warning:

His frothy Behavior may divert well enough as an Acquaintance; but is very unanswerable, I think, to the Character of a Husband, especially an English Husband, which I take to be a graver Character than a French one.

Letter 11, “To a young Man too soon keeping a Horse,” is a surprisingly lengthy treatise on the perils of premature equine ownership. As is evident from this excerpt, the tone of the letter is classic Disappointed Father, with a hint of passive aggression:

I am sorry to hear you have so early begun to keep a Horse, especially as your Business is altogether in your Shop, and you have no End to serve in riding out; and are, besides, young and healthy, and so cannot require it, as Exercise.

In addition to matters social and familial, Letters Written to and for Particular Friends covers how to write about traumatic and violent experiences. Sample letter 160, “From a Country Gentleman in Town, to his Brother in the Country, describing a publick Execution in London,” speaks with sorrow of the merciless crowd, which displayed “a barbarous kind of Mirth, altogether inconsistent with Humanity.”

An Old Man Reading (1728). (Image: Public Domain)

Ultimately, letter-writing manuals weren’t just concerned with instilling good grammar and a flair for narrative—like modern self-help books, they aimed to inspire people to live satisfying and morally luminous lives. The full title of Letters Written to and for Particular Friends ensures readers that the book offers “not only the Requisite STYLE and FORMS To be Observed in WRITING Familiar Letters; But How to THINK and ACT Justly and Prudently, IN THE COMMON CONCERNS OF HUMAN LIFE.”

The readers of 18th-century letter manuals would ideally use the letter templates to gain confidence, develop their own style, and become capable of writing their way into—or out of—any situation, whether it involve “an ungracious son,” a gentleman “who humorously resents his Mistress’s Fondness of a Monkey,” or “a Lady whose Overniceness in her House, and uneasy Temper with her Servants, make their Lives uncomfortable.” We’re all just trying to get along.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook