The Last Public Payphone Kiosk on the Streets of New York

How the once-ubiquitous convenience became a rare museum piece.

Before the mobile phone went from briefcase-sized accessory to attention-draining succubus, there was just one way to contact a friend, colleague, or family member while on the go: the payphone. And nowhere else in the United States were payphones packed as densely as in New York City. By 1960, a million of them had been planted like thickets of human connectivity from Wall Street to Staten Island.

But improvements in digital technology and the launch of the 3G network in the late 1990s untethered would-be-callers from payphones. Since then, LinkNYC, New York’s public communications network, has been slowly uprooting the telephones that once kept the city in touch. By the spring of 2022, there were only a handful of working payphones left in Manhattan, including four Superman-style phone booths on the Upper West Side and at least one payphone in the warren of subway stations beneath the city. On the streets of Midtown, where hundreds, if not thousands, of payphones once stood, just one last double kiosk remained.

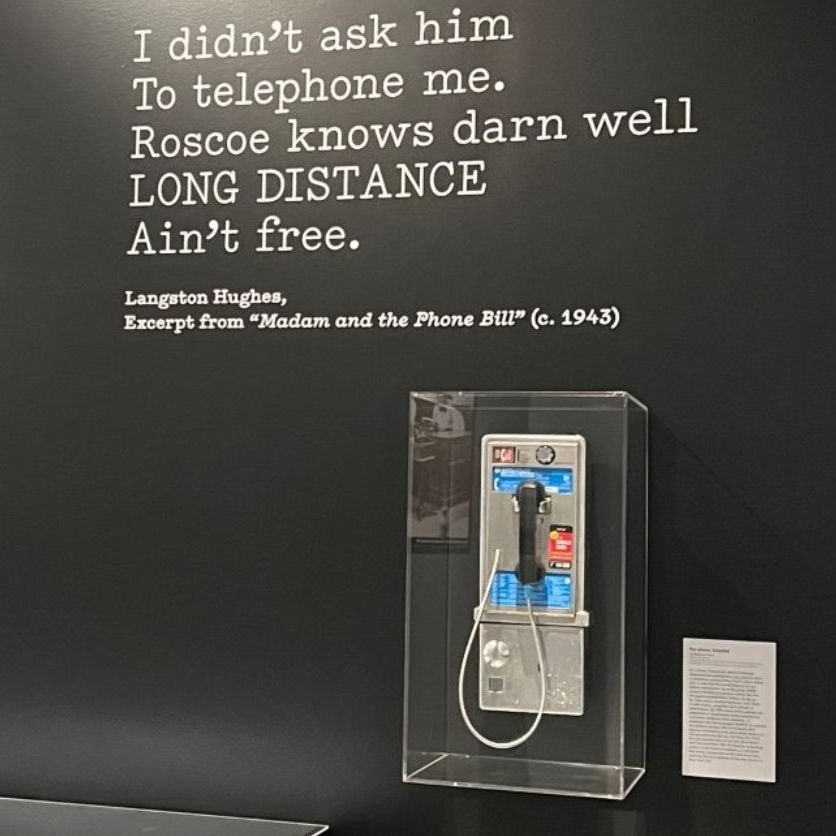

On May 23, LinkNYC pulled the lone surviving kiosk from the corner of 7th Avenue and 50th Street and sent it north to join the menagerie of extinct and endangered pre-digital inventions at the Museum of the City of New York’s (MCYNY) current exhibition, “Analog City.”

Although including New York’s last public payphone kiosk hadn’t been in the exhibition’s original plan, an “incredible coincidence of events” led to its acquisition. When the museum got the call from LinkNYC offering them the device, they were on the verge of opening “Analog City.” They even had the ideal spot for it, in the entrance wall to the exhibition.

To join the exhibition, LinkNYC surgically removed the payphones from their double kiosk shell and delivered one of them to MCNY’s collection’s department. There, the team documented its condition, built a custom shelf and backing for support and encased it in protective glass. Although it will never again be handled by a member of the public, let alone be connected to a telephone line, in its heyday, everyone from finance workers to bike messengers would have used this phone, says MCNY curator Lilly Tuttle.

“What was really exciting about this particular phone was its location and the incredibly high volume of calling that would have taken place,” she explains. It’s likely that this payphone would have rivaled those in busy neighborhoods and transit hubs like Times Square and Penn Station. In 1978, the New York Times reported that a payphone in the latter had an average pick-up rate of 5,500 times a month.

What the payphone did to exponentially increase the speed, scale, and universal accessibility of long-distance communication, the other analog artifacts at MCNY did for their respective industries between the 1870s and 1970s. Card catalogs made it possible to find and systematically keep track of huge volumes of information. Slide rules made it possible to calculate complicated math and science equations in record time. Pneumatic tubes made it possible to send paperwork whizzing across buildings on puffs of compressed air in a fraction of the time that Nancy could bring it down from accounting.

Some inventions in the collection were so revolutionary, they set off creative bonanzas that have rippled through time all the way to the present day. One of the most important was the 1884 linotype machine which, by making it possible for publishers to lay out full sentences instead of individual letters, infinitely sped up the printing process. “It transformed access to printed material and literacy,” says Tuttle. “Because of the linotype, newspapers go from four pages to six pages to multi-sections to being printed two times a week to being printed two times a day.”

The filing cabinet was equally game-changing in its time. Along with the invention of the first commercially successful typewriter in 1867 was the production of volumes of printed paper. When stored flat, their vast reams consumed floor and desk space like hungry two-dimensional caterpillars. But vertical filing cabinets allowed paper to be stored compactly on its long edge, giving offices the ability to manage and access information on a scale previously unimaginable, says Tuttle.

Even today, designers can’t quit the organizational innovations of the filing cabinet. Although digital technology has reassigned the production and organization of information to computers and the Internet, computer files are still stored in folders whose icons take the manila form invented for its vertical avatar.

In the long run, what the filing cabinet, and many other essential analog inventions couldn’t do was keep up with the pace of the work they made possible. “Speed is one of the challenges of the analog age,” explains Tuttle. “They have the means to create the volume but when the volume outpaces the tech you get this incredible backlog. There’s a finite speed or diminishing returns that you see in some of these industries.”

While digital technology has solved some of those problems while leaving others—issues like equity and access—in their place, MCNY tries not to judge whether its analog inventions were better or worse than those that followed. “The exhibition is this mixture of finding the beauty in everyday life and in the industrial and mass produced,” says Tuttle.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook