What Happened to the Severed Head of Peter the Great’s Wife’s Lover

Don’t believe the hype.

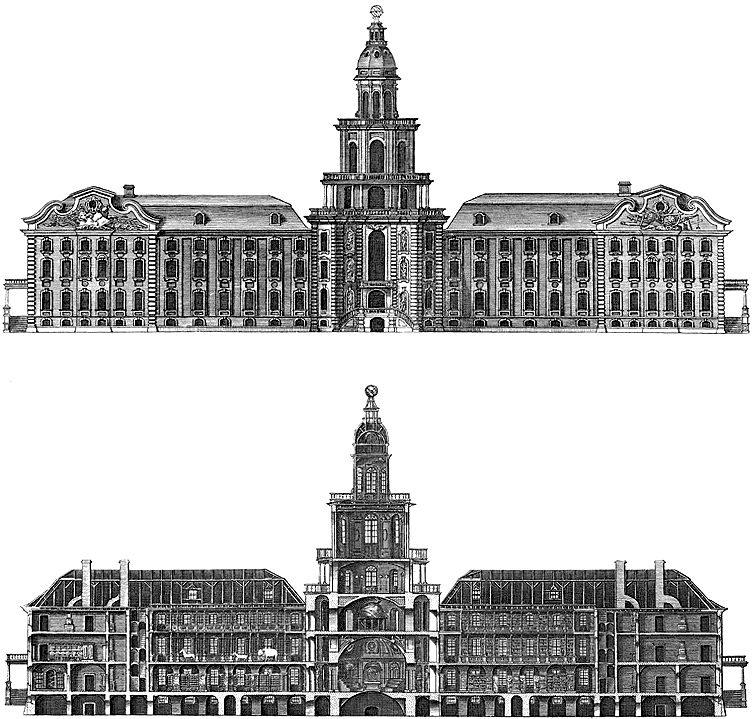

The Kunstkamera of St. Petersburg, Russia, is an art and ethnography museum stuffed full of more than 2,000,000 objects. Within its blue-and-white walls, you can find a taxidermied pangolin, Native American baskets, and more than a dozen jarred, pickled fetuses floating in a suspicious yellow liquid, prepared by Dutch anatomist Frederick Ruysch. What you won’t find, however, is what’s often cited as one of its main attractions: the severed head of the supposed lover of Peter the Great’s wife, in a glass jar.

William Mons was young, German, and exceptionally dashing—at least one observer described him as one of the “best-made and most handsome men I have ever seen.” He was ambitious and opportunistic, with a keen eye for which patrons might have his interests close at heart. These attributes shot him into the upper echelons of imperial Russia. Eventually, in 1724, he became the secretary and confidant of Catherine, the empress and Peter the Great’s wife. No one can say for sure whether their relationship was exclusively professional, however. “Lurid stories circulated,” writes historian Robert K. Massie, in his biography of the emperor, “including one that Peter had found his wife with Mons one moonlit night in a compromising position in her garden.”

There are plenty of reasons to doubt this story, Massie says. Taking a lover seems out of character for Catherine, who was very fond of Peter and well-acquainted with his furious temper. On top of that, the “moonlit night,” had it happened, would have been in November—no time for an outdoor tryst in frigid St. Petersburg. But other stories about Mons were also being shared, ones with more obvious basis in fact, including that he was soliciting hefty bribes from anyone hoping to have a message passed to the empress.

Peter, when he found out about this behavior, moved swiftly. Late on a frosty Wednesday evening in early November 1724, Mons’s papers were seized. That night, he was taken away in chains. Within a week he was sentenced to death, despite an attempt by Catherine to seek a pardon from her husband. Eight days after his arrest, he was dead—publicly decapitated in front of crowds in central St. Petersburg. While he died, Catherine was practicing a minuet with her daughters and their dancing master, and withholding any trace of emotion from her husband and the eagle-eyed public.

The execution had a profound effect on Peter and Catherine’s relationship, Massie writes. Even a month after Mons’s death, whispers at court said that they hardly ate together and no longer slept in the same room, though this chill appeared eventually to thaw. In the meantime, Peter battled a bladder illness and cirrhosis. (He had been a hard-drinking man, inventor of the vodka “penalty shot” for anyone who arrived late to one of his feasts.) Three months after Mons’s death, the emperor followed him, aged 53.

But what happened to the head famously and publicly removed from Mons’s body? For reasons known to only to the emperor himself, Peter had Mons’s head pickled in spirits and placed in a large glass jar. A few years earlier, when his own lover, Mary Hamilton, was executed for crimes including abortion, infanticide, and theft, he had had her head preserved in a similar way. Some accounts claim he presented Catherine with her secretary’s head. Others maintain he forced her to keep it by her bed—as a warning, perhaps. Certainly, after the emperor died, she kept the head in her possession until her death. This has led at least one biographer to speculate that it served as a grisly memento of a man she may have loved.

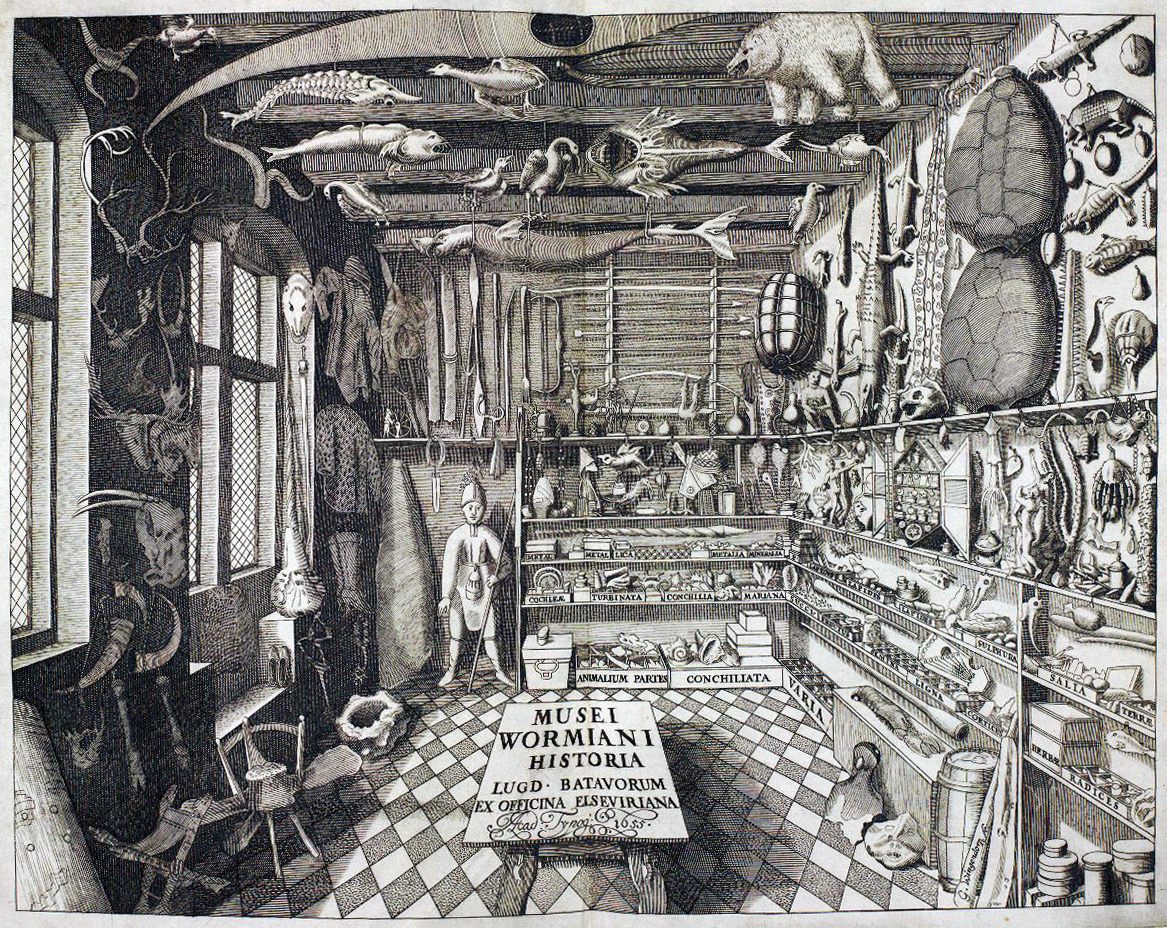

A little over 25 years earlier, in Dresden, Peter the Great had visited a kunstkammer, or “cabinet of curiosities,” with a collection of rare books, mechanical clocks, and other wonders. He was so inspired that he resolved to start his own museum of natural history, which he opened in 1718. Peter offered Russians between three and 100 rubles for “specimens” of so-called “freaks of nature”—dead and pickled in spirits or double-distilled wine, or, more lucratively, alive. This was partly to dispel common beliefs that such “monsters,” as he referred to them, were the work of the devil, rather than the simple products of nature. Soon the collection boasted an eight-legged lamb, a two-headed baby, and other unusual natural phenomena. It came to be known, as it is today, as the Kunstkamera.

Catherine died in 1727, a little over two years after her husband. The head found its way into the Kunstkamera, where it remained for half a century, even through a devastating fire in 1747. In the 1780s, Catherine the Great, the wife of Peter the Great’s grandson, spotted it by Mary Hamilton’s head on a dusty shelf, while walking by with a friend. “Princess Dashkov and Catherine remarked on the wonderful preservation of the two beautiful young faces, still striking after the passage of fifty years,” the scholar Oleg Neverov wrote in 1985. Some sense of propriety took hold, and she had them buried. Precisely where underground these two young, comely heads wound up seems to have been lost.

So you won’t find the severed head of Peter the Great’s wife’s lover in any museum, and certainly not in the Kunstkamera, not any more. But the Kunstkamera does have a veritable trove of human parts—heads, organs, limbs, and other medical artifacts. The story of Mons’s head—if not the head itself—fit right in.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook