Meet the Former Cook Who Draws His Every Meal

Itsuo Kobayashi’s art showcases the beauty of everyday Japanese food.

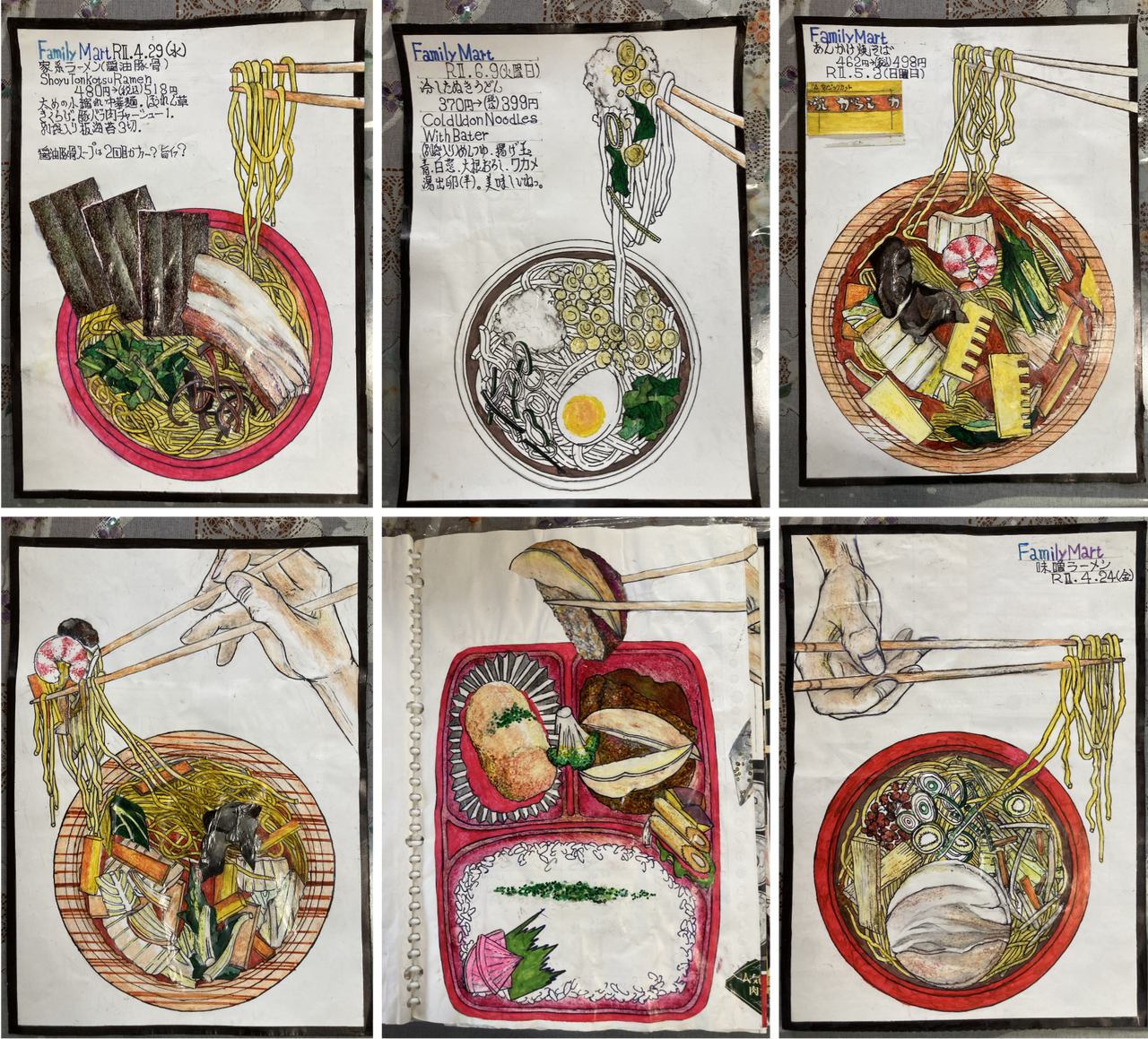

A marbled slice of tonkotsu pork rests on a bed of yellow noodles, nestled next to three shiny green sheets of nori, some boiled spinach, and a few shreds of kikurage, or wood-ear mushroom. A pair of disposable chopsticks raises a tangle of noodles above the red bowl, as if headed to a waiting mouth just off the edge of the page. A description of the meal is printed next to the drawing, along with the price, date, and source: Family Mart, a Japanese convenience store.

Itsuo Kobayashi draws what he eats every single day. While his drawings are individually compelling, each discrete element rendered in loving detail, his body of work as a whole gives an intimate window into everyday Japanese food: not the haute cuisine that is lauded by international chefs, celebrated on foodie sites, and shown off by the Japanese government. Instead, these meals are picked up at a bento stand or a convenience store and scarfed on a rushed lunch break, or on a tray in front of the TV. It’s the inexpensive survival food of students, bachelors, and anyone without the time, tools, or inclination to cook from scratch.

Kobayashi sits on an adjustable bed in the living room in his home in Saitama, Japan, a table piled high with things in front of him: a cup filled with pens and markers; stacks of papers, flyers, and books; remote controls for the TV and air conditioner. Next to him are more wobbly hills of paper on the floor, the peaks reaching the height of the bed. Plastic bags filled with more papers and file folders are tied to the sides of the bed and tray table. “Come in, come in!” says Kobayashi, switching off the TV. “Sit wherever you can.”

Kobayashi worked in food service from a young age. Starting at age 18, he worked at the same soba shop for 18 years. He attended cooking school, worked a stint in a sushi shop, and prepared meals for the elderly in nursing homes. Altogether, he worked with food for more than 20 years, until a combination of company closures and physical disability caused him to retire.

Today, Kobayashi lives with his elderly mother and spends most of his time in bed. Though he has always been interested in art—he was in the art club in high school and loved to draw even as a child—his obsession with drawing his meals started when he was working in nursing homes, and intensified as his physical mobility diminished. “For 12 years, my body has been like this, so I’m either watching TV, sleeping, or sitting here drawing. I’m not much of one to read or study,” he says. “So I mostly draw every day because we eat every day.” Neither Kobayashi nor his mother is able to cook now, so all his meals are delivered from the convenience store, bento shop, or grocery store.

Kobayashi started working with a physical therapist and a social support center more than a decade ago. A few years back, social worker Kiichi Nagashima visited Kobayashi on a home visit. “I saw all these notebooks with food drawings randomly piled around the bed,” says Nagashima. “The impact of picking them up still remains in my mind.” Nagashima encouraged Kobayashi to exhibit his work, starting with a few gallery shows and pieces in the Saitama Prefecture Art Show for the Disabled. Kobayashi’s work started to get noticed by “outsider art” collectors, including Nobumasa Kushino, an art dealer in Hiroshima. From there, Kobayashi’s work circulated outside of Japan, from inclusion in art books to pieces at international shows such as New York’s Outsider Art Fair.

Kobayashi says each piece takes a few weeks to complete, though he jumps from drawing to drawing, working on them in fits and starts. “Time is something I have a lot of. Because I’m not doing anything else,” says Kobayashi. He collects flyers, receipts, and labels—which make up a decent portion of the piles of paper around the bed—and uses them as reference materials as he sketches. He mostly works on the backs of old calendars, using pens, colored pencils, and markers from the 100-yen shop. People give him nice art supplies and paper, he says. “I have them saved. I don’t want to waste them. But since I have the old calendars … I draw on them.”

Kobayashi loves eating delicious food. But nothing he’s ever eaten, he says, has ever cost more than 2,000 yen, or around $19. “There are meals that cost 3,800 yen, or a course that costs 5,000 yen. But I’ve never eaten it. I’ve tried to remember, but I haven’t, and nobody has ever treated me to it either,” says Kobayashi. His favorite subjects to draw are his favorite things to eat, such as nabeyaki udon. “And I think, boy, that was good, really good!” he exults.

Each drawing helps preserve the joy in his simple meals. “When I draw katsudon, I can remember how good it tasted,” says Kobayashi. “Then there is a difference in how it tasted, because I drew it.”

But his art has also built him a bridge. “I’ve been sitting here for 12 years, leaking pee and poop, but my drawings have been all over the world,” says Kobayashi. “I don’t even know how to work a computer. Even the phone I use is a flip phone, and I’m behind the times.” Yet his loving depictions of Japanese food have brought him admiration, a little bit of fame, and, most importantly, visitors to his door. “People take time out of their busy schedules to come out and see me,” he says. “It makes me happy.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook