How Japanese Canadians Survived Internment and Dispossession

A new exhibit traces the experiences of seven narrators before, during, and after World War II.

When Yon Shimizu heard the news that Japanese forces had bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he was on his hands and knees, scrubbing his family’s linoleum floor. Living in a rented house in Victoria, British Columbia, with his sister, two brothers, and their widowed mother, he was listening to the radio while completing his chores. He raced from the room to tell the rest of his family. “I was frightened and dismayed,” he recounts in the prologue to his book, The Exiles. Life had never been easy for his family, he adds, “but none of us were really prepared for the devastating events which were to unfold in the coming months.”

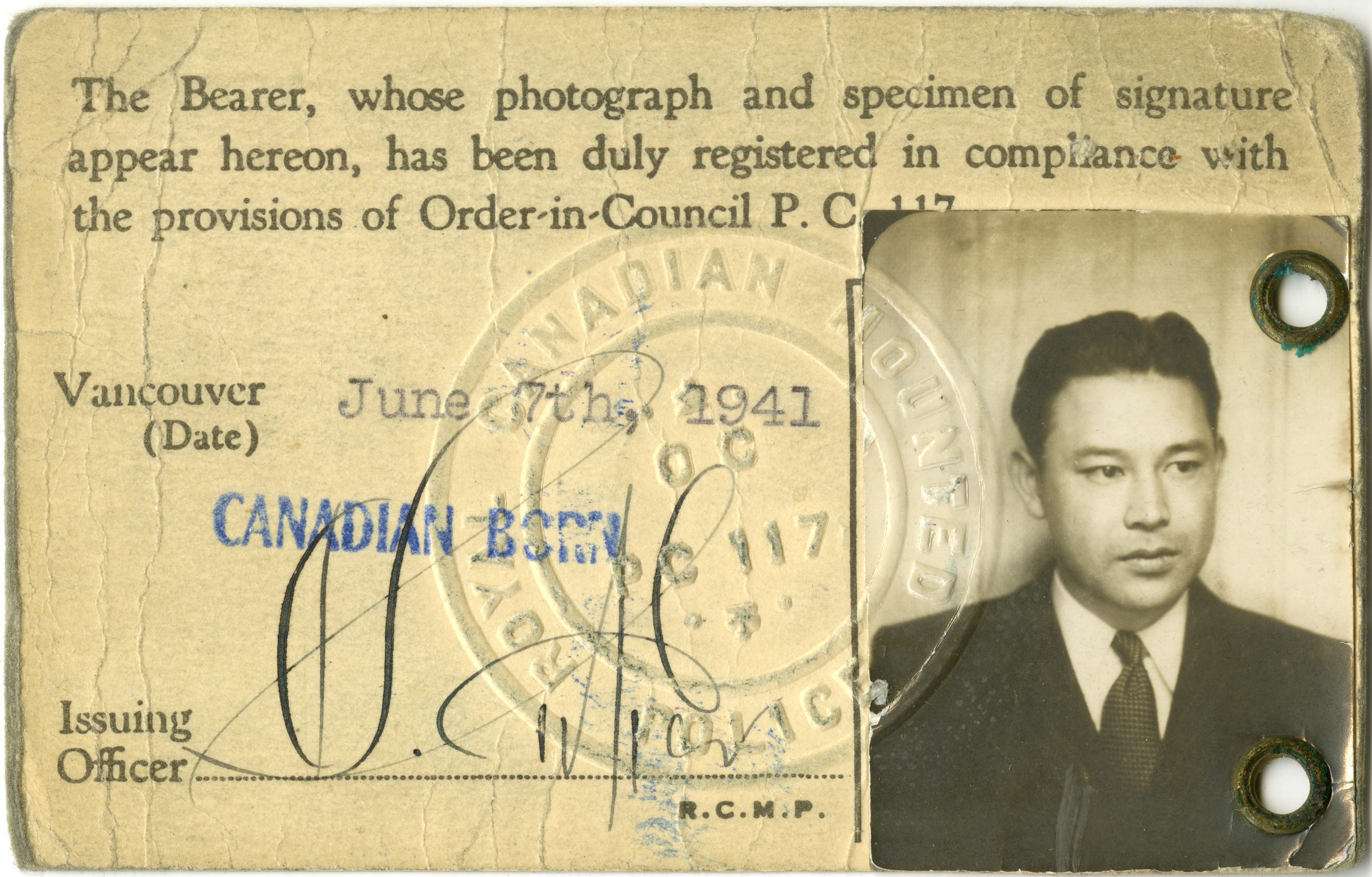

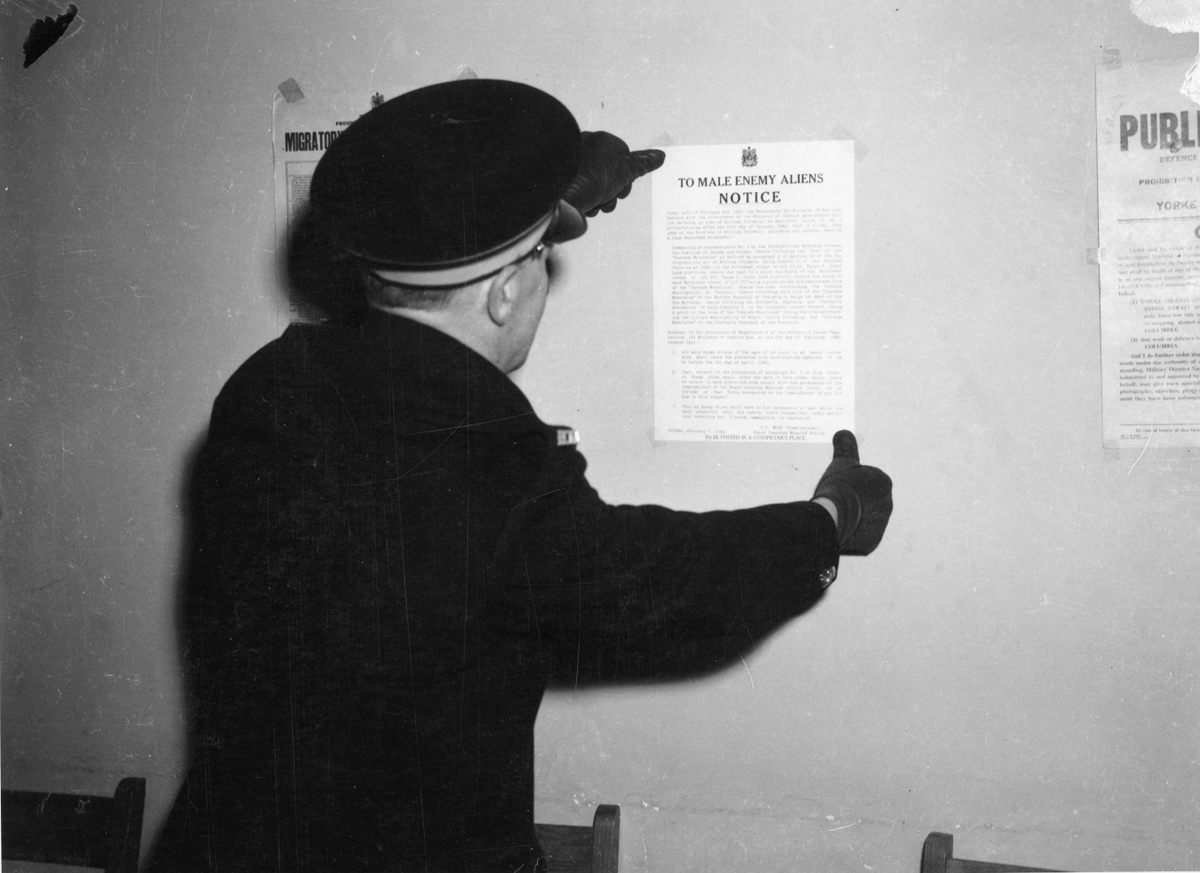

In 1942, the Canadian government declared a “protected area” along the Pacific Coast—a buffer zone between the water and the Japanese-Canadian communities that had flanked it. Under pressure from officials such as Ian Mckenzie, a cabinet minister from British Columbia, elected officials at federal, provincial, and local levels insisted that the Japanese Canadians who lived there be forcibly relocated. Nearly 22,000 people—roughly 90 percent of the Japanese Canadian population at the time—were uprooted.

Many were first gathered in a facility in Vancouver’s Hastings Park, the site of the sprawling Pacific National Exhibition, which still hosts an amusement park, horse-racing track, and other attractions. At Hastings Park, families were splintered—husbands separated from wives, children pried away from their parents. There, Japanese Canadians were housed in barracks or former animal stalls on the fairgrounds. From there, they were shipped out by car or train and scattered around the interior of British Columbia or farther east. Some were transplanted in Ontario, more than 2,000 miles away.

The daily realities of internment* varied from one family to another. Some were crowded into large, purpose-built centers, while others lived in buildings that had been converted to hold them. Some were recruited into labor contracts, and others lay down roads or harvested sugar beets. Some lived in so-called “self-support camps,” independent settlements that they set up with government approval. (One was in a resort on the shores of British Columbia’s Christina Lake.) Several thousand were stripped of citizenship and deported. The homes and properties that they were forced to leave were ransacked, and ultimately seized and sold by the government.

This period of systematic disenfranchisement lasted well after the combat of World War II had ended. Surfacing the history of this time remains an ongoing project. Since 2014, historians, elders, archivists, community leaders, and others have worked to excavate and preserve stories about this period as part of The Landscapes of Injustice project. Their work has led to a book and a new exhibition, Broken Promises, at the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre in Burnaby, British Columbia. Atlas Obscura spoke with Landscapes of Injustice Project director Jordan Stanger-Ross, a historian at the University of Victoria, about compiling this history and presenting it to the public.

The project and exhibition emphasize that these policies had a ripple effect through years, decades, and generations. How did they affect families after the war?

This wasn’t just a wartime policy. Since the restriction on Japanese Canadian return to the coast wasn’t lifted until 1949, most of the internment era was postwar. All of the possessions and homes and businesses and farms, family pets—every form of possession we can imagine—were looted and stolen and destroyed by neighbors and seized by the federal government. When the internment finally ended and Japanese-Canadian citizenship was restored, many of them had to start from virtually nothing.

They were prohibited from reinvesting in real estate, and the funds that were derived in the sale of their assets were highly restricted, and paid out in a kind of an allowance. I think any of us can imagine that for folks that had established careers and lives, built farms, or were close to retirement, the stripping away of all of their assets, and forcing them to use all of the capital from the sale of all their assets to just sustain themselves in these remote places, had very long-lasting implications for their families on a material level and emotionally—in every facet we can imagine.

I often think about this kind of lesson of the dispossession in relation to a letter than an individual Japanese Canadian, Rikizo Yoneyama, wrote to the Custodian of Enemy Property in 1943, when he learned that his farm, which he’d owned for a couple of decades and had developed by hand, was being forcibly sold. He was almost 60 and had put two of his children through university, and was anticipating putting the other two through university based on the income from the farm. He wrote and said it was worth more than they were selling it for, and he couldn’t just start again. He essentially begs, please reverse this decision, please don’t sell the farm. Hundreds of letters, thousands of letters like that went to federal officials, and they had a form letter with which they responded, “we understand that the sale of your property can be a personal matter, but it’s the policy of the government.” The flip side is the multigenerational benefit that someone who purchased a farm like that would receive.

For the exhibition, how did you find the right mix of voices to speak to people’s varied experiences during this time?

Four major themes carry through the research, and those are reflected in the exhibition and in its structure. First, that the dispossession involved the deliberate killing of home—that homes were destroyed, beyond merely uprooting and internment, though those are themselves devastating policies, obviously. Second, that dispossession required sustained work—ongoing work of administering the properties and dealing with the communications from Japanese Canadians, and the advocacy of Japanese Canadians to deal with the administrative state and its control over their lives and funds. Third, that dispossession required what we call “reasoning wrong.” That is, as the government shifted gears from holding property in trust to forcing a sale, they needed to articulate why they were doing that in legally defensible ways, and Japanese Canadians challenged that rationale. We ask, “What do people say that they’re doing, and how are those ideas challenged?” And then finally is the claim about the permanence of dispossession, those longstanding benefits and losses.

The co-curators, our post-doctoral fellow, Yasmin Amaratunga Railton, Sherri Kajiwara of the Nikkei National Museum, and Leah Best of the Royal BC Museum were excited about these ideas, and also wanted to integrate those claims with the stories of individuals who’d be foregrounded in the exhibition.

Kaitlin Findlay, our research coordinator, and a research assistant, Trevor Wideman, worked with the curatorial team to come up with a long list of potential narrators. These would be people we followed from before the internment—their settlement in Canada, some of them their origins in Japan—through the internment and afterwards. Ultimately, there were seven narrators selected, on the basis of economic diversity, family situation, age, and geographic diversity, as well as the ones for which we had the richest resources, including objects that could be shown in a museum.

Are there any specific objects in the exhibition that you think will help visitors empathize with these families’ struggles?

One example is a ledger or invoice from a store in Vancouver. The owner, Rinkichi Tagashira, had hundreds of these ledgers printed up, thousands of pages, at the beginning of the 1940s. He had piles of these. His grandson, Charles Jinnouchi, went to university postwar and took these blank ledgers and used them as notebooks for his calculus homework in the 1980s. Charles describes the emotional impact of trying to work his way through university on these pages from his grandfather’s stolen business, and the motivation that provided him to stick with it.

So much of the work of dispossession was administrative. Is that represented in the show?

At one point, you turn a corner and enter what’s called, in the exhibition, the Offices of Injustice. You see a very large-format photograph of an office with a mid-century triangular desk with little lamps on top. And the curatorial team created a replica of one of these desks, which holds a replica case file for each of the seven families. (It’s curated—an actual archival case file can be hundreds of pages long, and these are maybe 10 pages.) It’s a physical case file; you can pick it up and put it on the desk and read the correspondence and documentation of the loss of property. (There are medical gloves and other COVID precautions in place.) There’s also a big map to show the displacement of Japanese Canadians, and a big display that conveys all the different agencies of government that came together to execute uprooting and dispossession. There are oral histories and letters of protest, as well.

Was there anything that was particularly difficult to convey?

The challenge was to convey the bureaucracy in a way that was not boring. I think any of us that have dealt with the state, whether it’s the frustration of waiting for a driver’s license or permits, I think we realized that all of these small details matter, and the way that an individual official, someone who works a desk, really impacts what the policy means in our lives. How do you convey those processes and interactions in a way that doesn’t feel like a dry description of the functioning of a government office? So we use the case files and try to limit the text and stick with what’s important.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

* The Landscapes of Injustice team uses “internment” to describe the variety of conditions that Japanese Canadians faced, including widespread dispossession and curtailed movement. We’ve followed its wording here, though there is ongoing discussion among scholars and community members about other words, such as “incarceration,” that may apply.

** Correction: A caption originally stated that this photograph shows Bamfield Harbor. It shows the Annieville Dyke on the Fraser River.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook