In 1988, One Rogue Worm Shut Down 10 Percent Of The Internet

A computer, circa 1988. (Photo: German Federal Archives/WikiCommons Public Domain)

On November 3rd, 1988, about 6,000 internet users booted up their systems and noticed something strange. Normally speedy programs were moving like molasses. Networks, riddled with weird repetitive instructions, were barely grinding out regular commands. If administrators tried to override the foreign processes, more popped up, like a sinister game of Whack-a-Mole.

The system administrators picked up their landlines and started dialing each other. The inevitable had finally happened. The internet had been infected by the first super-villain in computer history—the Morris Worm.

Today, a worm that infected a few thousand machines would barely make the local papers. But in 1988, the Internet was a very different place. It consisted of about 60,000 computers total, and the people behind the keyboards were, as an MIT team put it, “academic, corporate, and government research users, all seeking to exchange information to enhance their research efforts.” Though security concerns were sometimes discussed hypothetically, the atmosphere was more small-town, where “people thought little of leaving their doors unlocked,” as one reporter put it.

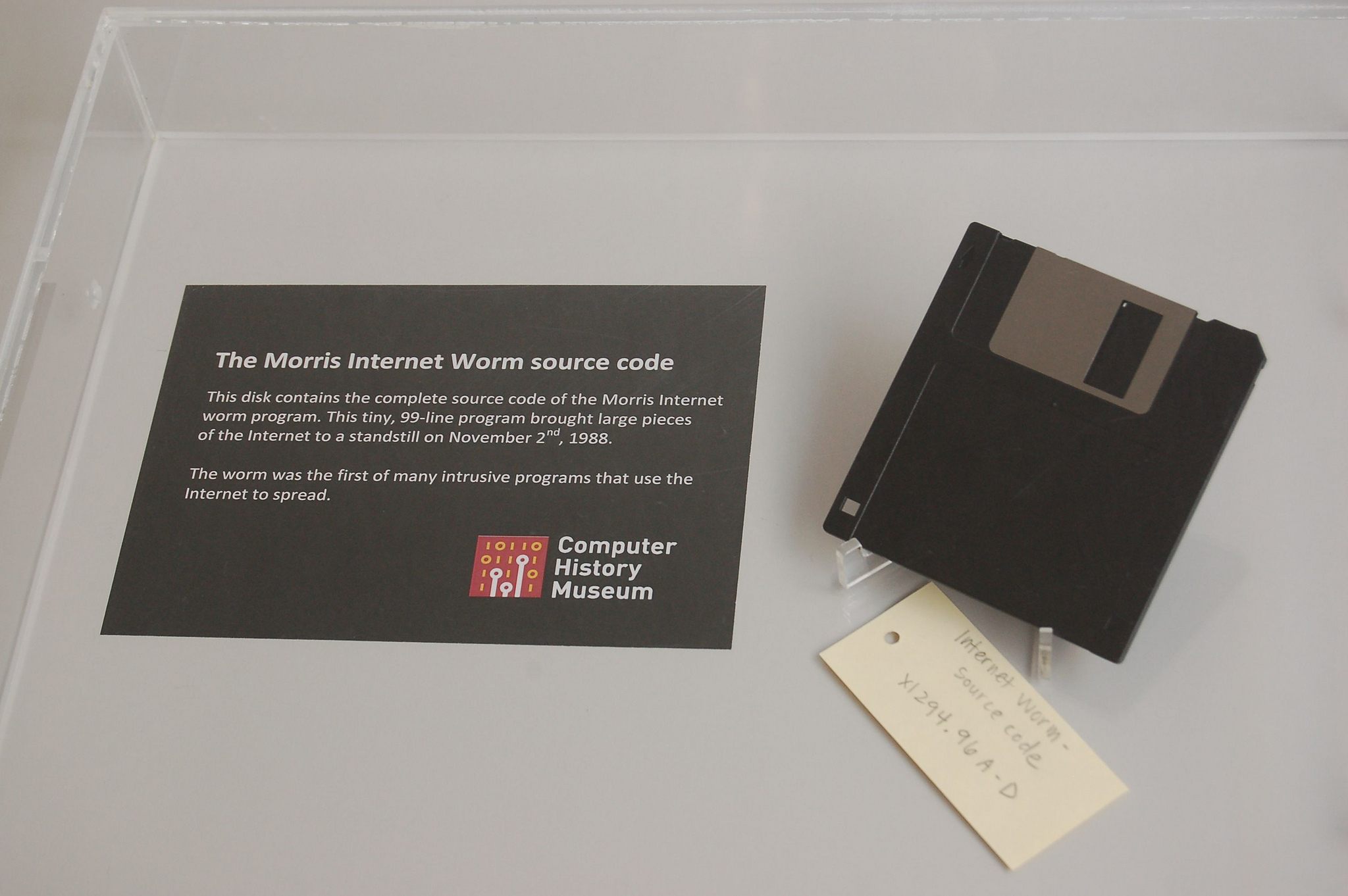

The Morris Worm, imprisoned forever in a floppy disc. (Photo: Intel Free Press/Flickr)

Still, it was a fast-growing, increasingly important part of the world—and Robert Tappan Morris, Jr., a 24-year-old computer science whiz, wanted to see exactly how many computers were hooked up to it. Morris, a Cornell graduate student who preferred his own projects to homework, wrote what he intended to be a sneaky, exploratory program that could snake through connections and probe the limits of the network without revealing its presence. Morris’s father, Robert Morris Sr., was a government computer security expert, and, in a strange twist, Morris used his dad’s research to find the loopholes he exploited to build the worm.

At about 6 p.m. on November 2nd, Morris loosed his creation from a public MIT account (either to cover his tracks, or to piggyback on the institution’s credibility, depending on who you ask). It immediately started ripping through the Internet. First it broke into email accounts, often by guessing “obvious passwords,” such as those that appeared on a short list of common words, or “the last name spelled backwards.” Next, it took advantage of loopholes in the standard “Sendmail” email program to send itself to new targets. It ran itself over and over again, clogging up mail servers and preventing them from working correctly.

This last feature wasn’t part of the plan. By 2:30 A.M., a panicked Morris knew he had made a ”colossal mistake.” He called a friend at a Harvard computer lab and asked him to post an anonymous message on Usenet, an Internet-wide bulletin board, with an apology and instructions on how to disable the worm. But everyone was in battle mode, and didn’t notice the message until days later, when coalitions across the country had already dissected and understood the worm, and cleaned up most of the damage, at significant cost.

Reformed worm-master Robert Tappan Morris, 15 years after unleashing his creation. (Photo: Almudena Fernández/Flickr)

“The rogue program… did not launch missiles, disrupt the stock market or shut down the telephone network,” wrote the New York Times two years later. “But it did scare the wits out of a lot of people who run computer systems.” The media did their best to scare people, too. “It came from California,” intoned PBS News reporter David Boeri. “It spread across America… it arrived at MIT in the middle of the night.”

Dangled in front of the computer science community, the Morris worm inspired a number of debates. Many disagreed on whether it was more properly described as a virus or a worm, a distinction that boils down to which part of the computer you define as the “host.”

The University of Southern California settled on worm and promised to take readers through ”the infection, its festering, and cure,” while NASA’s more clinical Ames Research Center called it a virus. The contrarians at MIT thought that, behavior-wise, it acted more like a bacterium. Clifford Stoll, one of the leading worm-slayers, described it as a cuckoo, “laying eggs in other birds’ nests.”

Unlike this guy, the Morris Worm was non-segmented—and was thus, according to MIT researchers, not a worm. (Photo: Squeezyboy/Flickr)

Along with the rest of the country, the experts mounted something of a personal attack on Morris, arguing over whether he was impressive or irresponsible. Another report, commissioned by Cornell in the wake of the attack, concluded that Morris was normally a decent person, and that this anomaly was the product of ”the unfocused intellectual meandering of a hacker completely absorbed with his creation and unharnessed by considerations of explicit purpose or potential effect.” In other words, Morris may have made the worm, but the worm controlled him.

This was, of course, not a good legal defense. The commission concluded that, despite some defenders who held that the worm brought vital security flaws to light, Morris’s action was less like calling attention to the provincial internet’s unlocked doors and more like “driving a golf cart on a rainy day through most houses in a neighborhood.” He was brought to court, and became the first person to be convicted under the relatively new Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Though his attorney had feared the worst—multiple federal felonies, five years in prison—Morris was instead sentenced to three years of probation, 400 hours of community service, and a $10,050 fine.

Twenty-seven years later, in a time when hackers are more likely to make the news for stealing and revealing data than for brute-force-crashing servers, the Morris Worm has gone from terrifying monster to history lesson, a cute, wriggly forerunner that put everyone (slightly) on guard. The source code is available online for interested perusers. An original infested floppy disc is on display in Silicon Valley’s Computer History Museum. And Morris, in a feat of infiltration surpassed only by the worm itself, is now a professor at MIT.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook