Human Eyes Might Not Notice a Good Forgery, But Computers Could

Artificial intelligence might thwart art forgers once and for all.

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk, painted in 1908. (Photo: Public Domain)

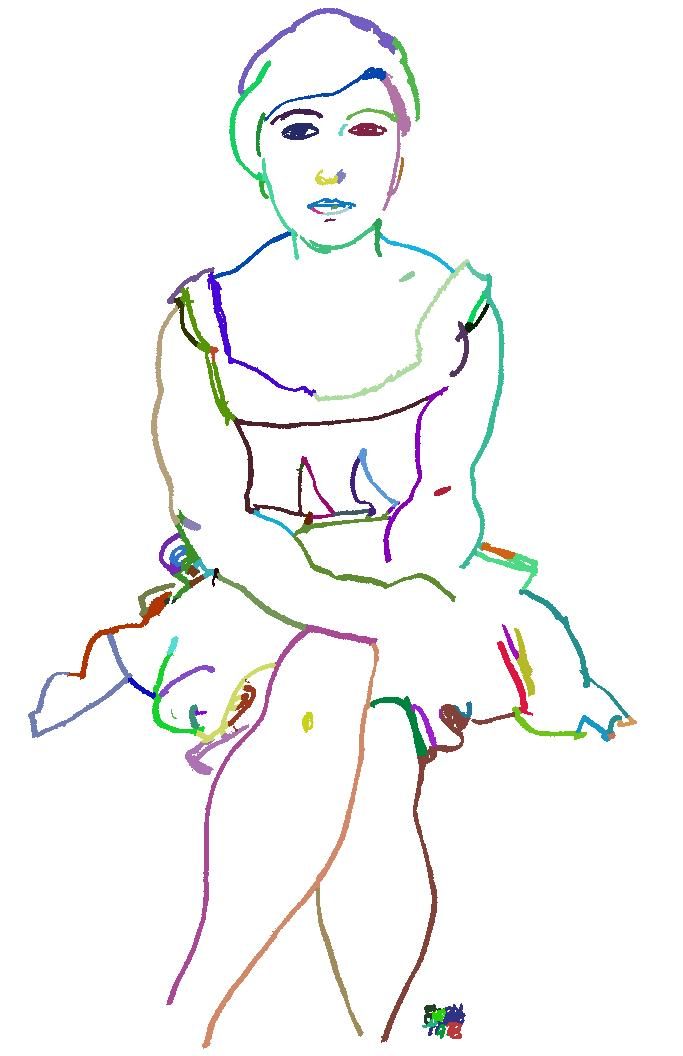

On any given day in a lab in New Jersey, a humming machine traces the lines of a hand-drawn image: a woman’s face drawn by Matisse. The machine highlights each new line it sees, recording and cataloging its thickness, shape, and the artist it was created by.

But the computer isn’t merely scanning the image, it’s learning. The Art and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at Rutgers University is currently teaching the machine to appreciate and understand art, and the subtle differences within a painting or drawing.

“The A.I. will be able to tell a Van Gogh versus a Matisse, for example, based on the visual elements that are somehow unconscious to the artist,” explains Ahmed Elgammal, Professor and Director of the lab.

Scientists have been exploring artificial intelligence in relation to art for years, and while artificial intelligence systems can now make paintings of their own dreams, humans still have the only brains capable of appreciating them. This is where the Art and Artificial Intelligence lab comes in. Computer scientists there hope to bring artificial minds closer to mimicking human intelligence, and their work may also help solve a problem that has plagued the art world for hundreds of years: art forgeries.

From the machine at the Rutgers Laboratory, which tries to trace individual lines for analysis, used here on a work by Egon Schiele. The various colors are to differentiate the lines. (Photo: Courtesy Natalie Zarelli)

There is great potential for an A.I. detection system to identify counterfeit artworks. But first the researchers have to teach their electronic brain to learn many centuries worth of art history and technique. To do this, Elgammal and his fellow computer scientists took pictures and high-resolution scans of thousands of paintings, and entered them into their computer system. Over time, the computer traces each line in the drawing, and analyzes the image against others using machine learning algorithms, which the computer uses to count and quantify different tiny aspects of what it “saw.”

All of this is happening inside the “brain” of the computer, which uses information in its artificial neural network to recognize visual patterns in the artwork. We can see what the computer “sees” based on its output data, which is shown as a flat image on a screen that summarizes the computer brain’s results. When the computer is learning how Matisse tends to draw, it colors the lines it has learned and differentiates one small stroke from the next, remembering it forever.

The artificial intelligence that was developed at the Rutgers University lab has yet to be used in any investigative capacity to detect a forgery for a gallery—it’s still in its early stages. However, it is pushing past previous research where A.I. was used to detect forgery, using similar techniques.

Nearly a decade ago, art forgery research from the University of Maastricht in the Netherlands found that the number of brush strokes in a given painting were indicative of whether a painting was authentic; Van Gogh, for example, tended to make the same number of brush strokes in a given area. When compared to a famous counterfeit Van Gogh painting, one of dozens sold in the 1920s by the German art dealer Otto Wacker, a computer decided there were far too many brush strokes for it to be a true Van Gogh, something that humans eyes would never be able to see on their own.

The National Gallery in London. AI could also help with the study of art techniques. (Photo: Xiquinho Silva/CC BY 2.0)

New research at the Art and Artificial Intelligence lab will also be able to understand this concept in deeper detail, using the texture and exact shape of each brush stroke to develop a range of characteristics that exist, on average, in an artist’s work.

Considering that contemporary art forgery scandals disturb the value of art while calling the abilities of art historians and dealers into question, it’s possible this technology could help clean up the art trade, though the primary goal of the A.I. lab at Rutgers University is to help an artificial brain think more like a human. “Art, and engineering art, is an ability that only humans have over other creatures,” says Elgammal. “If a machine is going to be intelligent, it also has to have this ability of looking at art and understanding art.”

These days, when a computer scientist asks the A.I. to notice something—for instance, which of several paintings is the most innovative for its time—the computer’s artificial intelligence is able to draw those conclusions. Recently, the lab’s computer began to pinpoint characteristics from individual artists; as it learns, it will be able to tell whether a painting seems authentic by analyzing minute characteristics of an artist’s brush, pencil or pen strokes. Using high resolution scans and photographs of paintings and drawings, the Artificial Intelligence can get a good look at thousands of details humans aren’t able to analyze.

The neural network is building on past research; last year the lab taught their computer to categorize roughly 62,000 paintings and rank them by how innovative the images were. The computer was able to note similarities in paintings created centuries apart; the resulting map of art placed paintings by Goya, Michelangelo and Vermeer (who is one of the most forged artists of all time) among the top most creative images for their eras, with the “Mona Lisa” by Da Vinci, and paintings by Durer and Ingres closer to the bottom.

The authorship of this painting, now attributed to Vermeer, was under scrutiny for many years. AI can be used to differentiate the visual cues of artists and so help spot forgeries. (Photo: Public Domain)

The computer learned composition, subject matter and color during that time, but today it is ignoring those characteristics, and learning to recognize the smallest brush stroke. Once that is mastered, says Elgammal, “then we can reach something that can avoid forgers being able to manipulate the machine.”

After looking at hundreds of various artists’ drawings, the computer’s A.I. can now identify the individual strokes of Matisse and Picasso with an accuracy of up to 80 percent, according to Elgammal. “If the machine can tell what are the characteristics of certain artists, advances can lead to the machine also reading art based on style, although that will still be ahead in the future,” he says. Currently, the AI can detect a line’s thickness, curvature, shape, tone, and smoothness. Eventually, the technology will be able to read a broader set of details within context.

Artificial intelligence critics, some of whom believe computers may one day replace human value in society, are likely to be wary of a robotic mind appreciating art. But Elgammal believes that artificial intelligence is not likely to replace art historians and aficionados. “In reality we are far behind in replicating human intelligence, even of that of a toddler,” says Elgammal. “The machine really complements human ability, it’s not a competition, and we will not be at a stage where it will be replacing the human identity—at least, not anytime soon.“

The Artificial Intelligence Lab’s system is also meant to complement other technologies that verify a painting’s authenticity, such as testing the age of the canvas and the chemical composition of pigments, and using infrared and hyperspectral imaging. The lab also employ artists and art historians to lend their knowledge to the computer base. Elgammal and his team will be publishing the results of their work soon, hopefully by the end of 2016.

Visitors at the Art Institute of Chicago. AI can be used to learn about composition, color and subject matter. (Photo: Phil Roeder/CC BY 2.0)

The computer scientists at Rutgers believe that not only will studying art help artificial intelligence systems become a better tool for art historians and art dealers, they may help us understand how and why we understand art ourselves. In the past few years some neuroscientists have theorized that art directly stimulates certain neurons in our own brains, and reverse-engineering this process for computers could potentially shed light on the process.

Indeed, the Art and Artificial Intelligence Lab uses models of human neural networks in their research. The technology can also help uncover new facets of art history over long stretches of time using statistical analysis to learn exactly how styles and techniques evolved.

“That’s opening doors for me and new questions about art which I think is very interesting, because art and science has somehow been two different camps,” says Elgammal, whose own love of art is what drew him to the Art and Artificial Intelligence Lab. “Now it’s time to make science and art come back together again and start asking these questions.”

Plus, if the fear of human workers being replaced by A.I. ever materializes, it may be somewhat comforting to know that our robot overlords are the cultured sort.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook