How the Military Ran Its 1970s Psychic Intelligence Program—Many Memos, Naturally

The DIA’s 1984 memo (Image: National Security Archive)

For decades during the Cold War and into the 1990s, the United States military ran a program that used “psychoenergetics”–psychokinesis, telepathy, and, most prominently in this case, “remote viewing”–to collect intelligence.

This isn’t some clever promotion for the new X-Files. The collection of records on the program released by the National Security Archive has recently expanded to 51 separate documents. As befitting a government agency, many lay out the incredibly weird protocols of psychic espionage in boring memos, endless strings of acronyms, and, of course, budget analysis.

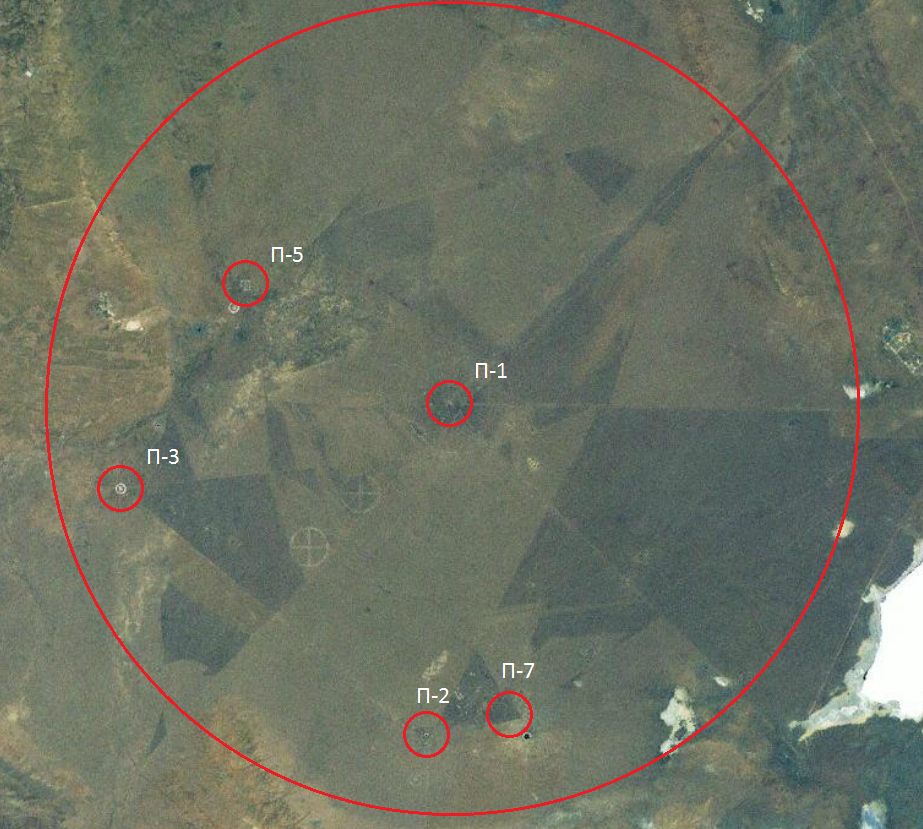

The program (or programs, as the collection of different psychic efforts had many different names over the years) developed an emphasis on remote viewing, which involves using psychic powers to somehow see something in a place away from where you actually are located. This began after early experimenters in the 1970s were able to provide detailed information about a Soviet R&D facility. After that, the military fielded a secret remote viewing team for years.

Located for at least part of the program’s existence in Fort Meade, Maryland, this small group spent its time trying to see places far away. They would be tasked with intelligence missions like trying to find missing aircraft. Their name, throughout much of the early to mid ’80s, was “Grill Flame.”

What’s striking about the military’s psychic research–besides the initial surprise that it existed at all—is the clash of worlds that it implies. The military is supposed to precise, and government bureaucracy, mundane; psychic powers are supposed to be hazier, less reliable, and significantly more mysterious than budget reports or interagency memos.

The results of mushing the two together can be surprising. For instance, in order for the remote viewing program to go forward, it needed a health-and-safety clearance from the military brass. The reason: “The Army General Counsel determined that this psychoenergetics activity employed by the Army…did constitute experimentation on human subjects.”

This bit of information comes from a 1985 memo, part of a newly assembled sourcebook on the Defense Intelligence Agency. In the mid-’80s, another branch of military intelligence was transferring the program to DIA, and this memo to the Deputy Secretary of Defense details the implications of the human testing designation. Basically, that designation adds a new layer of bureaucracy to the psychic program: every year, a high-up military official had to okay it.

“As DIA is now taking responsibility for this program,” the memo concluded, “you are requested to approve continuation of the program.”

The Soviet nuclear testing site that was viewed using psychoenergetics (Image: Joe-4/Wikimedia)

Classifying remote viewing an experiment on human subjects implies that this work was somehow risky, or dangerous to the participants. And to a casual observer, it might be hard to imagine that a group of people sitting in a room and trying to exercise psychic powers were going to be harmed in any way.

Besides the isolation, though, there may be some dangers to psychic warfare. In An End to Ordinary History, a 1982 account of Soviet and American research into parapsychology that’s fictional but based on real people and events, one character warns that the people working on a Soviet remote viewing project have “an alarming rate of alcoholism and cancer” and “nearly every study shows that hexing shortens your life.” And in The Men Who Stare at Goats, a nonfictional account of the U.S. military’s psychic research, author Jon Ronson is told that a man who actually killed a goat by stopping its heart with his mind suffered, too. “As it turned out in the evaluation he actually did some damage to himself, as well,” one source tells Ronson.

And when Ronson does meet the alleged goat-killer, the man describes the sympathetic and disturbing feeling he gets when practicing that same skill on a hamster. “Inside of me I couldn’t even breathe,” he says.

There’s no information in the DIA document about what, exactly, the military consider the risks to the remote viewers were, but it does indicate that there’s a protocol for dealing with it. And the program did have a distinct advantage, perhaps one that let it be re-authorized for so many years. “Remote viewing is inexpensive,” the author of a later DIA memo, writes, “The principle cost of remote viewing collection is the people involved. There is little expensive hardware, since for the most part, the people themselves are the equipment.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook