How a Mythical Imp that Snuck Up People’s Large Intestines Became a Symbol of Japan

The kappa may be adorable, but it has very few boundaries.

A kappa doll decorates a water lily pond in Japan. (Photo: pattang/shutterstock.com)

Although the kappa-maki, a slim cucumber roll, is a vegetarian standby on sushi menus all over the globe, few realize that it is named for a folkloric water sprite whose reputation was never so innocuous as his namesake dish. Once thought to inhabit the rivers of Japan, the kappa was known for all sorts of waterside evil, from pranks on farm animals to drownings of children.

Only one talisman could ward off a kappa: a cleverly wielded cucumber. The malicious imp could be appeased by a cucumber thrown downstream, with the name of a family member carved onto it. But eating a cucumber before swimming was considered a deadly mistake.

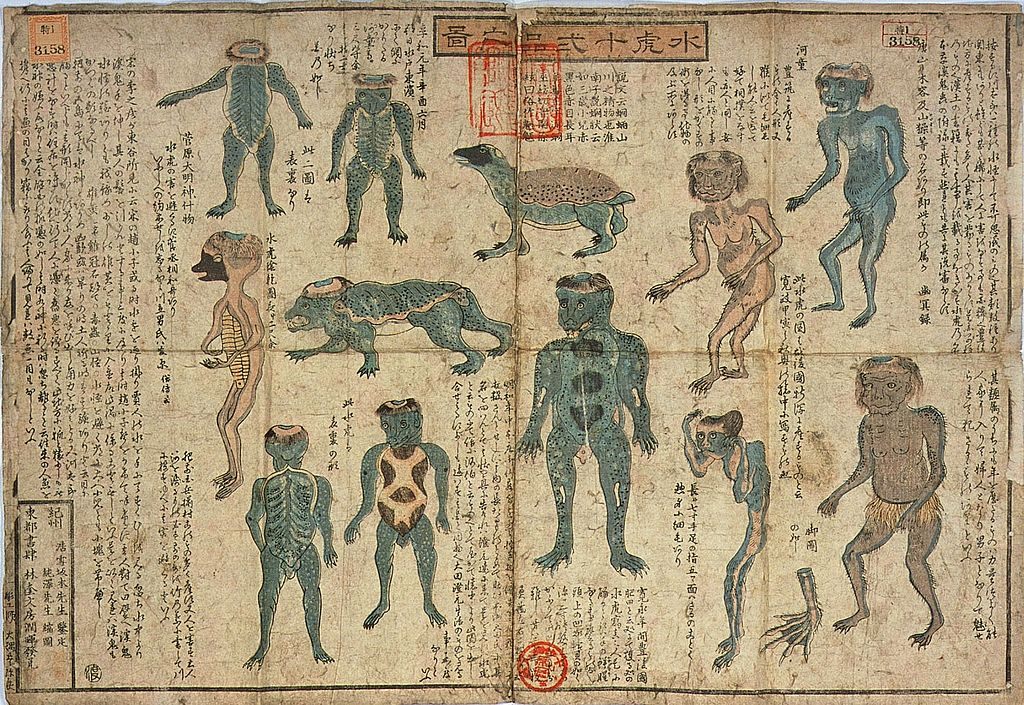

A mid-19th century scroll showing different types of kappa. (Photo: Public Domain)

Today, kappa repelling measures are a thing of the past: Japan’s people do not so much fear as adore the kappa. A perfect storm of 20th-century pop culture and civic pride initiatives has made the kappa an omnipresent mascot in Japanese life, signifying the kappa’s epic trip from the dank, foreboding depths, to souvenir shelves all over Japan, and even a dedicated temple.

Despite their ubiquity, it can be hard to describe exactly what a kappa looks like. Like a character from the Sanrio wheelhouse, kappa are generally depicted as an amalgam of several different creatures. They often take on the form of an aquatic animal, like a frog or a turtle, and have been known to sport webbed feet, shells, and beaks, but they can also appear more like a human or monkey.

If this does not sounds like an adorable combination of features, the kappa was also not prone to adorable behavior.

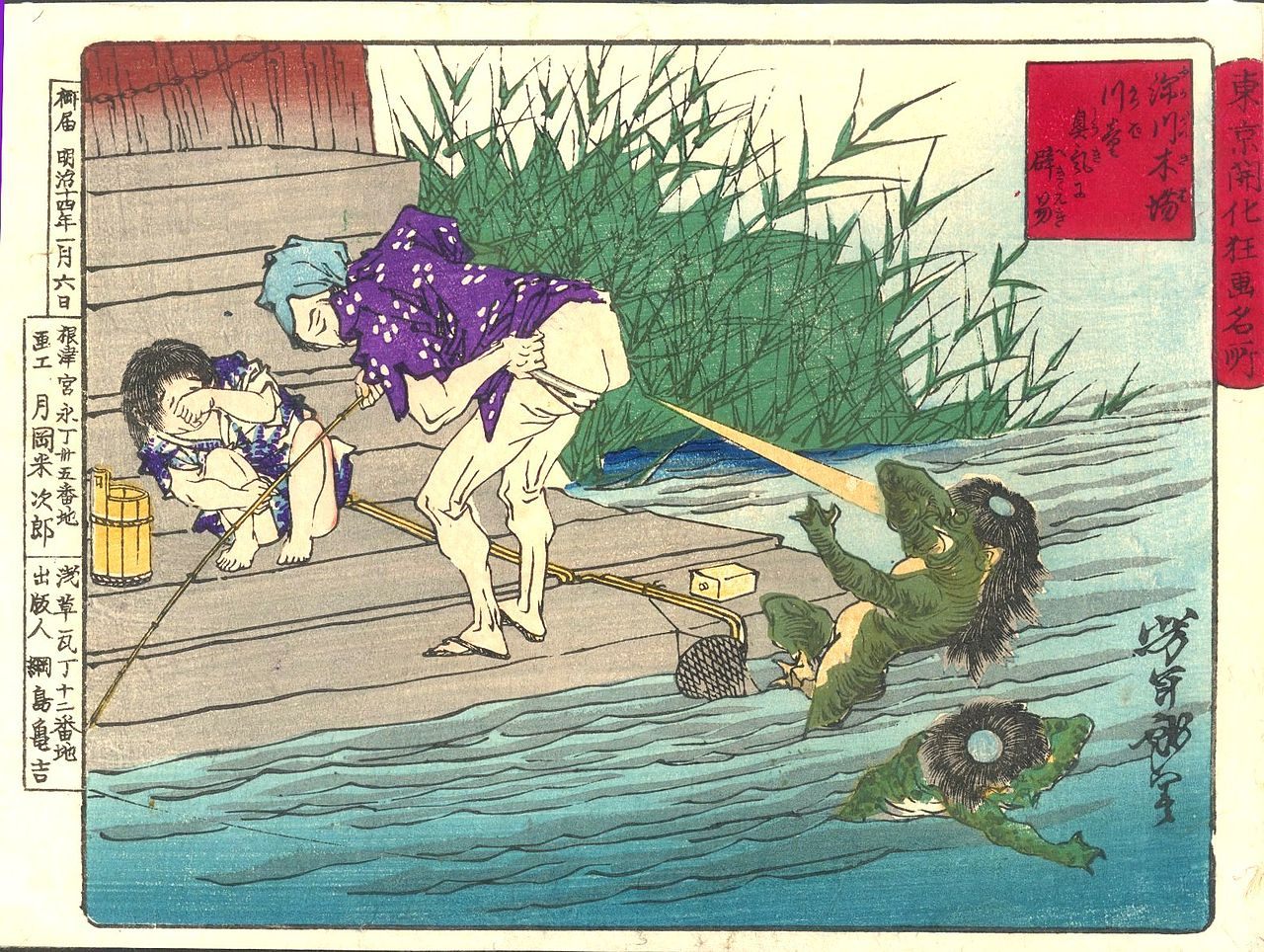

Repelling a kappa with a fart, 1881. (Photo: Public Domain)

If drowning children sounds brutal, then consider the preferred object of their thievery: the human liver. As river dwellers, kappas were thought to lurk beneath the old fashioned toilets that overhung the river and to use that vantage point to truly invade people’s private space. By reaching through the anus, kappas could snatch the internal organs of an unsuspecting toilet-goer. Collateral damage in this transaction was a mythical organ called the shirikodama, a little globe that was believed to plug the anus.

The only absolute constant of the kappa’s appearance is the sara, a saucer-shaped vessel attached to the top of its head, that looks not unlike a monk’s tonsure. Since the kappa’s life force was said to be contained in this sara balancing atop his head, its fate was a little precarious.

An illustration of capturing a kappa alive, from the early 1800s.. (Photo: Public Domain)

Ways to weaken or even kill a kappa are quite plentiful: a person can literally kill a kappa with kindness by engaging it in the ritual of polite bowing. Or if this doesn’t work, sumo is a sport that kappas love, despite the fact that it is not conducive to steady movements or upright posture.

If sumo doesn’t help vanquish the kappa, the creature’s limbs are also not solidly attached and therefore easily pulled off. Much of kappa folklore revolves around humans using a detached limb as a bargaining chip to elicit a promise of good behavior or tips on effective bone-setting (another kappa skill) from the kowtowed imp.

A meditating kappa in the Kappabashi district of Tokyo. (Photo: Vassamon Anansukkasem/shutterstock.com)

But beginning in the 1920s, the kappa’s legend began to evolve beyond its ghoulish origins. In the dystopian 1927 novella Kappa, by Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, author of classics like The Nose and Rashomon, the kappa is recast as a familiar, and somewhat pathetic character.

The novella’s human narrator, upon arriving in the realm of kappaland, describes the scene of an infant kappa’s birth: “When it comes to the moment just before the child is born, the father—almost as if he is telephoning—puts his mouth to the mother’s vagina and asks in a loud voice: ‘Is it your desire to be born into this world or not? Think seriously about it before you reply.’”

This sensitive father kappa, though in a delicate position, has evolved a long way from stealing livers and anus-plugs underneath river bathrooms, and the infant kappa replies in kind. He decides to forego being born because he “shudders to think of all the things he will inherit from his father” and he “maintains that the kappa’s existence is evil.” The kappa had developed a conscience.

Kappa figurines for sale. (Photo: yukinobu n/shutterstock.com)

After Akutagawa brought kappas over to the human side, domesticated them, and perhaps even stamped out their “evil heredity,” the people of Japan were ready to adopt them. Japanese supernatural folklore scholar Michael Dylan Foster attributes much of the change in the perception of the kappa to urbanization of Japan. The old beliefs became quaint—the people of the new urban Japan appreciated their cuteness, and the people of rural Japan recognized the shift and marketed accordingly.

Today, kappa have taken on personalities and roles just about as close to civic engagement as reformed water demons can get. Kappa on street signs promote traffic safety, or campaign against water pollution. The famous Jozankei hot spring even claims the kappa as a tourism mascot.

Kappa Plaza in Osaka, Japan. (Photo: Chris Gladis/CC BY-ND 2.0)

The presence of kappa in manga and anime has brought attention to the creatures even outside of Japan. The Nintendo video game Yôkai Watch is making sure kappa lore makes it to yet another generation—the premise of this game being that the player has a special watch that helps him sense haunting and mischief in the realm.

This means kids today have more effective options than hacked-up cucumbers when they head down to the riverbeds to face off with a kappa.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook