Highway to Hell: A Journey Down America’s Most Haunted Road

All illustrations by Matt Lubchansky

1.

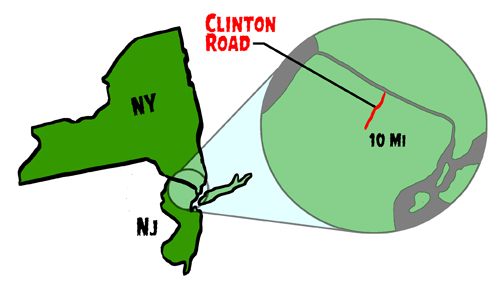

In a part of New Jersey where snakes slither slowly across a road, still coiled and yet somehow still moving; in a part of New Jersey where an insect that looks like a miniaturized bat sits on your windshield, menacing you while you make a sound that doesn’t sound quite like you from inside your car; in a part of New Jersey with a disproportionate amount of road kill in an already highly populated-by-road kill state; in a part of New Jersey where your phone cannot, will not pick up any kind of signal; here, in West Milford, in the county of Passaic, lies Clinton Road, a 10-mile stretch of haunted highway.

Like so many things in New Jersey, the hauntings of Clinton Road are populous and fragmented and mysterious. All around New Jersey, you can mention Clinton Road and people will say, “Yes, the haunted road, right?” And you’ll say yes and ask them what exactly that means to them, and they’ll tell you one of the many stories associated with the place but they’ll be vague: A dead child? A cannibal? A gang? A truck? Nobody has many specifics on the road except the aficionados, just an overall sense of its haunting. But it’s another way that Clinton Road is a microcosm of New Jersey: Its fame as a haunted road, among many haunted roads in a very haunted state, is about volume.

The pavement itself is innocent enough to look at. It is long and curvy and surrounded by tall trees and it is certainly not abandoned—following the winter, its potholes were filled more completely than on my highly-taxed, not-haunted street. There are hiking paths off the road, and even weirder, some houses. Especially at the opening of the road, some of the houses play up their Clinton Road-ness—a cobwebbed spinning wheel in one window, or a totally bizarre merry-go-round in another. But there’s also an accounting firm, and there’s also just some kids playing outside.

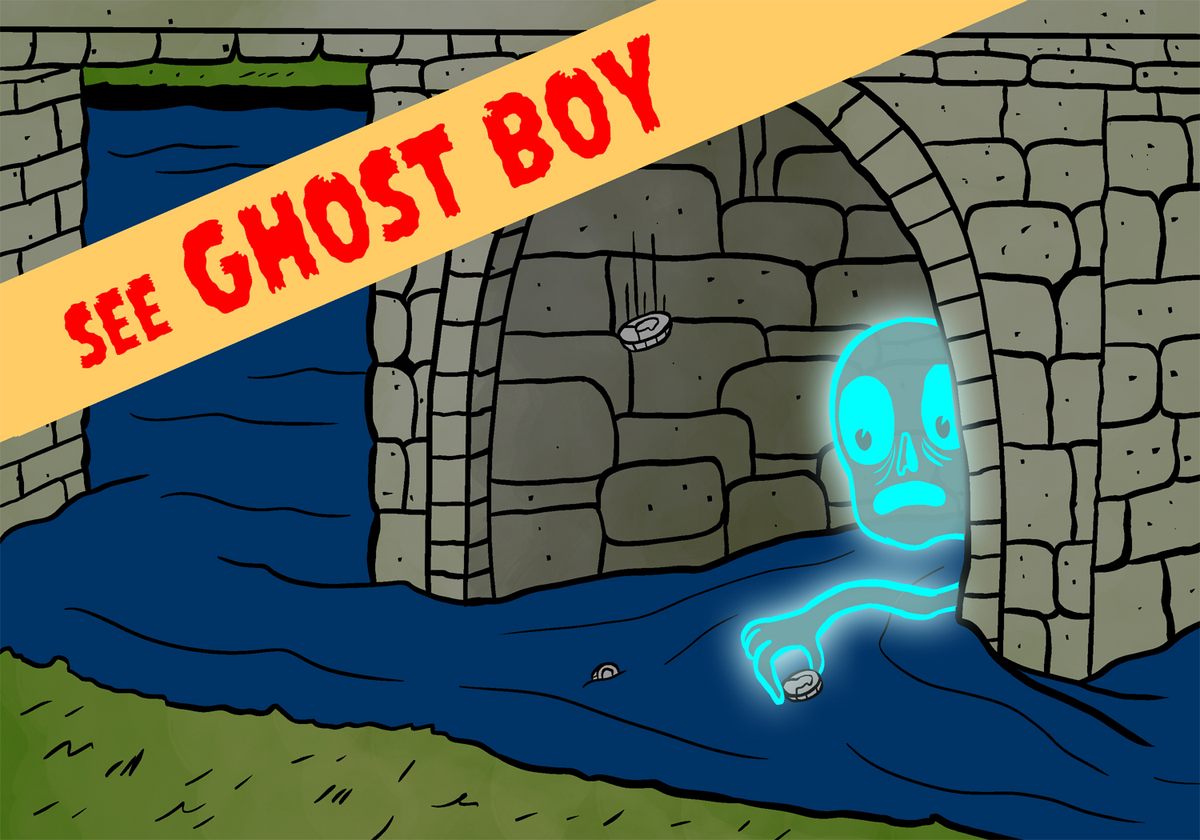

But, also: On this stretch of road, cannibals jump out of the woods to eat innocent passers-by. Satanists sacrifice poultry in the nether regions of abandoned castles. There are men in white hoods, and they are probably KKK, since once one of the hooded men stood in the road and stopped a truck full of stoned teenagers, only letting them pass when he looked each of them over, surely verifying their whiteness, the purity of their blood. The ghost of a dead boy haunts beneath the bridge at Dead Man’s Curve, roughly halfway down the highway; this boy, incidentally, throws your quarters back to you if you drop them in the body of water beneath the bridge. I have read that people know this for sure, that it is absolutely true, though the ghost boy is not your monkey. He will not perform reliably and there are many people who complain that they’ve made this 25 cent investment with absolutely no yield. There is a black pickup truck that will tailgate you out of nowhere only to mysteriously disappear, and I can even tell you that this happened to me several times over the course of my visits to Clinton Road in the last two months. There used to be reports of Clinton Road-specific weather reversals—snow in the summer, but those have dissipated, perhaps since there actually is snow everywhere in the summer because the weather is fucked.

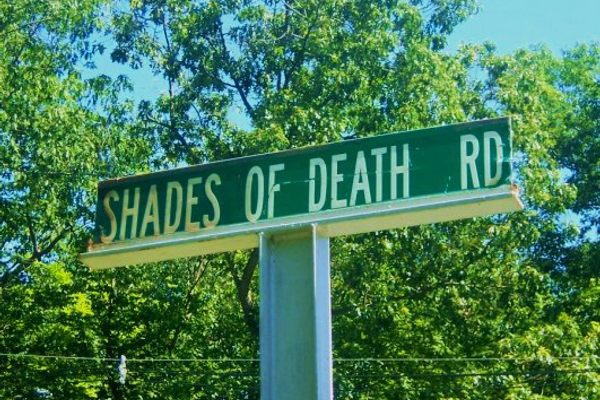

And yet, none of this really drew me to the story. For starters, Clinton Road has had its day. It’s what we in the media industry call “covered”: It has a Wikipedia page, several local TV and news-of-the-weird cable shows. The New York Times weighed in. It’s got a Daily News story, and also a Buzzfeed feature. (In this business, when Buzzfeed has covered you, you are covered.) If you are compelled by the supernatural and super-freaky, there are better and certainly less known places to visit. I could have easily gone with the far less known Shades of Death Road in Great Meadows, or even Jenny Jump State Forest, an actual state park haunted by the girl who jumped off a cliff when goaded by a Native American tribe. Or I could have written an entire book on just the Pine Barrens, where the Jersey Devil roams, cursed by its own mother to spend an eternity as a freak, unlovable to all, no sweet death to anticipate.

So Clinton Road’s cannibals did not frighten me, not even how scary all this is in light of the fact that my car’s hybrid battery is on the fritz, and who knows when it will go. Getting lost didn’t scare me either, even though I had moved to New Jersey from Los Angeles just three months before I was assigned this story. (I had grown up in New York, and so moving to New Jersey would have felt like a terrible fate, except for how much I had hated Los Angeles.) No, it was a simple addendum that I read at the bottom of a very long Wikipedia page that made my stomach go slack and my breathing become shallow.

At the foot of the road is the longest traffic light in the U.S.

2.

The Grasshopper Irish Pub & Restaurant sits on the tiny, incidental stretch of road between Route 23 North and Route 23 South; it also sits between the two lights. It’s the first building outside of Clinton Road proper, and the people inside do not seem to possess the anxiety that I believe people should have when they are so close to a haunted highway. It is a regular restaurant with people having lunch, a wifi connection, and flat Pepsi, passed along after I order a Diet Coke without even the perfunctory, “Is Pepsi okay?” (Has there ever been an enthusiastic yes to that?) The Yelp reviews had tempered my expectations. It is, after all, a restaurant named for an insect.

I am here to meet Dina Chirico. I will know Chirico when I meet her there, she told me over email, because she will be wearing her New Jersey Ghost Hunters shirt, which is a black shirt with a picture of a cartoon ghost wearing a Sherlock Holmes hat and looking through a magnifying glass at the state of New Jersey. She will know me, she said, because she is an empath.

Chirico started seeing dead people, or just hints of them, shadows and parts, when she was very young, and when she was a teenager, she learned how to manage this particular gift: She could turn a ghost away, or she could talk to it. She is not afraid of ghosts. How could you be afraid of something that isn’t trying to hide from you? Currently, she is a nurse, and also head of the Northern New Jersey Ghost Hunters Society, which is not the same as the Chuck’s Paranormal Adventures and is not the same as East Koast Ghost and is not the same as the more than 50 other societies devoted to paranormal research that I was able to find with a perfunctory Google search. She’s in it for the research; she doesn’t take money to do investigations. And she doesn’t ever use her gifts unless she is employed to. As a nurse, she does not tell the dead when they will die. She does not tell them what it will be like when they do. I have to beg her to tell me something about myself, because I can’t resist. But when I do, she is correct. More later.

I was introduced to Chirico by L’Aura, the head of the state’s Ghost Hunter Society, who explained why so many ghosts gravitate to New Jersey. It’s the water in the state that keeps the place so haunted, L’Aura told me. Water is a conductor for energy, and what are ghosts but energy? In certain places, certain matter keeps the ghosts well populated. For example, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania is a torrent of supernatural activity. You’d think it was because of all the deaths there, but no, really, Chirico told me, it’s actually because the layer beneath the dirt there is composed of quartz, and quartz, when it shifts, gives off a spark, and the spark conducts the ghost energy. Here in New Jersey, though, it’s the water and the lightning from the storms that keep the place just crawling with what the ghost hunters refer to, simply, as “activity.”

And it’s true. There is water everywhere, a cosmic joke, no a heavenly relief to my eyeballs after living for a decade in Los Angeles, a city that cracked and gasped with dryness. Clinton Road is surrounded by lakes and reservoirs, and that, L’Aura had told me, is probably what got it so haunted, and kept it so haunted, in the first place.

Ghosts are everywhere, but not everyone becomes a ghost. There are a lot of reasons that a soul might “stay,” as they put it, and here are two: There is unfinished business; there is someone still living who needs looking after. And the third one, which I will warn you caused me to take a deep breath and put my hand over heart, so staggering was this notion: “They just don’t know they’re dead,” she told me. “They just keep going about their business, unaware that things around them are changing.”

Is this as devastating to you as it is to me? Does this cause you, whatever your beliefs, to look at your hands and wonder if you’re really typing? If you’re really talking? If you’re really having sex and complaining about the TV noise in the next apartment and making grocery lists? What if you don’t know that you don’t need to be bothered by the TV noise anymore. What if you don’t know it’s ended and still you’re buying groceries?

What if you’re dead and still you are dieting?

I was raised religious, and when children are introduced to religion too young (this is now my working theory), they are stuck with the belief that anything is possible, and that’s not a great belief to have as a journalist who is investigating a haunted road. Religion in the hands of a hyperactive imagination isn’t a good thing. Once you place God into the mind of a child, once you set no limits on the possibilities, from burning bushes to archangels, you can never truly regain the skepticism that should have been taught to you when you first regarded the world.

It is because of this that I have to keep reminding myself that there is no such thing as ghosts, that there is no such thing as an empath, but the longer I spend with Dina, the harder it is to remember this, especially when I suggest we take my car for a drive down Clinton and Chirico is game but she also wants to know if we should take her car, since, she says, she senses that I’m having car trouble.

3.

Before Clinton Road was haunted, it was just criminal. It started in the 19th century as a dirt road whose utter geography allowed nefariousness to fester. The road is lined with thick woods, and bandits waited behind trees for travelers to rob and harm. There was industry a few miles in, a hike’s down from the road—a productive iron works that made cannonballs—and so people traveled to and from the site with money.

Clinton Road’s more modern history can be found in a list of testimonies from a magazine called Weird NJ. Most of the stories have a breathless dude-you’ll-never-believe-this tenor, and they often begin with a bunch of bros going to Clinton Road to intentionally become scared after filling up on weed and beer. In an issue of Weird NJ that is dedicated completely to Clinton Road (later collected into a book, published in 2000), the editors suggest that Clinton Road, with its few landmarks and long stretch of blank pavement, is an empty canvas upon which to paint your worst fears.

A sampling of sentences from these testimonies:

“The Wiccan in me always drew me to strange places in order to find others like me to bind [sic] with.”

“He had this German Sheperd [sic] and this real spooky piece of black felt-like cloth over his head.”

“Being superstitious, we brought along some stuff, like a cross, a Bible, some fireworks and a laser pointer.”

“When we think of Satanism in general, we usually picture adolescents as immature men dressing black robes and trying rebel against society in their own way.”

“As soon as we did, we heard a stage noise, similar to funning over a bottle—but there was no bottle.”

“The noise seemed like it was…almost inside us.”

In the woods, people swore they saw blinking red eyes, like in a Scooby Doo episode. They saw the chicken carcasses that had to be the result of satanic sacrifices. There were satanic verses scrawled near Bearfort, also known as Clinton Castle or Cross Castle. The Castle had been a grand estate in the early part of the 20th century, but in the end was sold to the City of Newark (which is nowhere near the city of Newark), and eventually razed, to much local consternation.

Then there is, of course, the Ghost Boy, who became my favorite. Nobody knows anything about the Ghost Boy, though someone mentioned that he was hit by a car while he was picking up a quarter in the road. The hall of records, which is not so much a hall as another room in the municipal building that houses the police station in West Milford, has no information about a boy who died there, and they would if he died during a time when a car could kill you. Which is not to say it’s not a perfectly apt place to die: The curve comes out of nowhere, though, and it’s tempting to speed down a road that’s both scary and that has no outlets, especially when you are being chased by a phantom pickup truck. A few years back, a man who was speeding down the road went off the bridge and hung in his car upside down suspended. He didn’t die in his car; he was removed from it. It had been a terrible winter, and they say it was the shock and the impact that did the final job on him. He died a few hours later.

4.

Clinton Road’s prominence on the internet and in the imagination of the New Jersey resident is both the pride and the thorn in the side of two men named Mark, Mark Sceurman and Mark Moran. They’re the proprietors of Weird NJ, the magazine (and website and accompanying travel guidebook) that collects all that is strange, haunted or bizarre in New Jersey. Sceurman, a graphic designer, was putting out a stapled, black and white newsletter that recounted legends he’d heard when Moran, also a graphic designer, reached out to him in pre-Internet 1992 to say he’d like to help contribute.

Together they traveled, Moran told me, like Alan Lomax recording blues in the South: Town to town, listening to the legends people just know from being where they are—which manor is haunted, which house does it up big for a holiday, which same mystery happens. Think of them as cultural anthropologists or historians of folklore and you’ve got it right. You’d call them from, say, Totowa and you’d tell them about, say, Annie’s Road, your local haunted road, and they would come out and listen, and write it down, and publish it.

They are not quite believers—belief is beside the point. They are merely trying to capture local legend and make a record of it. Later a reader will write to them and say that they went to Annie’s Road and saw no ghost. But they never said you’d see a ghost. They just said someone had said they’d seen a ghost. Big difference. The Marks also have never claimed to see a ghost. They’ve seen some weird shit. Once they were called down to the Pine Barrens to see a bunch of white shirts hanging starched and perfect from trees, and it was pretty terrifying. But they’ve never seen anything they could pretend was really otherworldly.

It was the Marks who put a special section in their book about the lore of Clinton Road, they who own the most annotations on the highway’s Wikipedia page, they who devoted an entire special issue of Weird NJ to just Clinton Road. And yet: They were bored of my questions before I even asked them. Everyone wants to talk about Clinton Road, and it gets old because they suspect that people wouldn’t want to talk about it if they’d just buy the magazine. If they’d just buy the magazine, all their curiosities would be satisfied! And within the annoyance there’s probably a teaspoon there of reporters like me knocking down their door and asking for information and reprinting it without credit (for the record, about 80 percent of Clinton Road knowledge I have put into this story comes from the glorious and exhaustive issue 43 of Weird NJ, a bargain at twice the price and available for purchase on their website). But more than that, there is something too easy, maybe even too lazy about Clinton Road. It’s a straight line up from their offices in Bloomfield, just a little further from the straight line to my house in West Orange. It’s just a right turn from a heavily trafficked road. It’s just a road so local to the civilization of the New Jersey that is a close commute to Manhattan.

Moran points out that this might also be its very appeal, and the key to its perpetuation. “Wayne, West Orange, all along Route 23, Cedar Grove. It’s all very densely populated. It’s an easy run up there for any teenager who gets their driver’s license,” he says. Not so with Shades of Death Road, which is a “real haul,” an area that is “so rural that it seems like you’re in another world.”

The others places are commitments. Clinton Road is a joy ride.

5.

I moved to New Jersey from Los Angeles, but I’m not from there, either. I’m from New York—pre-Brooklyn Brooklyn. The things that were scary to me when I was growing up were too real: New York in the pre-Giuliani 1980s was filled with muggers and broken windows and rapists. In Brooklyn, there were no ghosts or hauntings. There were no cannibals. We didn’t need them to be afraid. There were bad people who might do some bad things to you. The coach at the prep school I attended was raping the football team over the course of his 20-year tenure. Disgusting middle-aged men stood too close to me on the not-crowded L train. A man took my mother’s purse from under her arm as she walked to her car in a parking lot in early evening.

Los Angeles was scary, also for practical reasons: Every now and again you could see a coyote on a regular street. Sometimes the ground would shake and the phones would get jammed and you couldn’t ascertain if everyone you knew was okay because not everyone updated Facebook to say FELT IT. They told us we’d be drinking our own piss within the year thanks to drought conditions and I’d awake from dreams where I had become so dehydrated that I needed a water dropper applied to me to reduce the spongy cardboardness that my flesh had taken on as a result of rampant lack of drinking water.

But the hollow fears of hauntings are not totally foreign to me. For one year, I did live in a suburb—with my father, on Long Island. Long Island was a scary place. It had woods and houses that made noises and the dog would bark for no reason at the door sometimes. My friends and I would walk through backyards and thickets to get to the movies, movies where we’d watch suburban teenagers get murdered for lacking the sense to live in a city. Because the suburbs are for suckers, as anyone who has been murdered in a horror movie knows: So much darkness, so much space, so many bored people, so many checked out parents, so much potential for crime.

There was a night when we all walked through the dusk to go see Pet Sematary, if just the image of these teenagers walking through the woods doesn’t terrify you, and we did, a line of us, walking silently in silhouette against tall grass.

Afterward, a parent picked us up in the parking lot and took us back to David F.’s house, and some people made out in his basement, but the rest of us, bereft of an Internet that was still largely only being used by the CIA, told stories about ghosts we’d seen in our lives, or, more accurately, ghosts we’d heard other people had seen. Eric kept saying that his dog saw ghosts, that he’d follow them around, that it was foolish for us to think there was a dog whistle that only dogs could hear but that’s where it ended. A week later, my dog was barking in my kitchen, and he came to the den to get me. I was too afraid to go see what it was, and I ran upstairs to my father’s room, where he’d fallen asleep watching TV. I dragged my mattress to the floor of his room. Within a few minutes, I heard a slam. Not a small or short sound, but a real slam that had to be something being thrown across a room.

My relationship with ghosts changed right then. I had always been afraid of their stealth powers, that I might see them and not be able to convince anyone that I’d seen them—that so much would be unexplainable. But that night, I realized that the right ghost wouldn’t be self-conscious. The ghost who meant it would be loud and furious.

I’ll end this story the way good ghost stories end, which is with a mystery: The next day, my father yelled at me for knocking over a chair in the kitchen and not picking it up.

6.

If you would like to see someone get very angry very quickly, be sure to ask Lieutenant Keith Ricciardi of the West Milford Police Department about Clinton Road. His nose will flare and he will grit his teeth and talk through them and barely be able to even mention the Weird NJ guys (though he will) because of the information that they put out on the Internet “which is patently false.” It leads to all sorts of shenanigans.

And some of it is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Aside from that poor guy who died off the ghost bridge, there have been double dares that lead to grave injury. A few years back a guy would dress as a ghost or put on a hood and jump in front of cars. People with black pickup trucks would ride the tails of visitors, and if the visitors weren’t as stoned or drunk as the usual Clinton Road tourist, they would become enraged and try to run the SUV off the road. Someone died doing this, too.

All Clinton Road—a road Lt. Ricciardi likes to take his kids camping on, if you can believe it—is a heap of trouble for the town, and all that trouble begins at Weird NJ. “They must make money off their website by advertising,” he sneers, as if making money off a website is a dirty wish, as if it is not the modern American dream. “And I think that they just make up these salacious stories and people who are less than informed believe it, for whatever reason. Hey, if it’s on the Internet, it must be true, right?”

7.

Eight point eight miles from a Target; 6.6 miles from a Mandee discount women’s clothing store; 1.3 miles from a Dairy Queen, which is across the street from a billboard advertising a bank that reads “Trust us,” which, sure, I guess is creepy and foreboding, you will find the traffic at the base of Clinton Road. The light can be as long as four minutes, and as little as two (I timed it three times, and couldn’t get one solid number). The national average on a traffic light peaks at 120 seconds, so more than twice that—and it’s tedious, but it’s not really scary. If I’m honest, it’s hard to get worked up about a haunted road in walking distance of a Dairy Queen.

I went to Clinton Road twice, and both days had terrible ambience for this story: Sunshine and new season warmth. The street begins unceremoniously with an accounting firm. A few houses in, I found a man in front of another house, and I got out to talk to him. His name was Ron, and he wore a gold necklace that said “Mets” on it. He was planting shrubbery at his wife’s bequest. No, the house wasn’t cheaper because it was on a haunted road, he told me. No, he’d grown up around here, and didn’t I seem like a smart girl? Why would I believe in such legends?

I found nothing, miserable nothing, on my first visit. My friend Rachel and I hiked, all the way to the temple, now in ruins, covered with glass from six packs of Coors. We were there, alone in the woods, and it couldn’t have been less scary, and we couldn’t have been more disappointed. Deeper and deeper we went, getting lost even, trying hard to scare ourselves, but there was nothing. Later on the road, we passed Dead Man’s Curve, and it said “HE DIED HERE” on the concrete barrier in graffiti, and that was scary, or maybe I just find it upsetting now that I’m a mother. The scariest thing that happened that day was that we found a tick on Rachel’s shirt, but don’t worry, we got it off before it got to her skin. The other thing that happened that is remarkable, only because I’m searching, is that there was a very large turtle in the middle of the road when we came back, and briefly we wondered how it could have gotten to the middle of the road so quickly. We’d only been gone a few minutes.

The next time I went back to Clinton Road, it was a few weeks later, and I dragged poor Chirico, in my shitty car, and she explained that there are said to be time warps on Clinton Road, and perhaps Rachel and I were traveling back over or through time. (Maybe, but then why hadn’t I missed my chiropractor appointment later that day?)

Chirico and I got the Dead Man’s Curve, and brave Chirico, unscared Chirico, Chirico who will befriend the boy, she got out of the car and she called to the boy. “Little boy,” she called. “Come out and talk to us.” We offered his favorite thing, which is loose change, and then nothing. Chirico confessed to me that she felt no activity—less on Clinton Road than most other places, which seemed odd, but there you go. I told Chirico I was sorry for wasting her time, and she maybe felt sorry for me and suggested I check out Shades of Death Road, a more reliably haunted place.

I didn’t find it odd. Rather, it just confirmed what I was beginning to suspect was behind all the New Jersey hauntings: That we lived in a place that might as well have hauntings because most of the population never faces real danger. They go through life numb, this is my observation, and they talk about the weather and they talk about the humidity and thank god it’s Friday and not for nothing, always not for nothing, and sports sports sports. But for a moment there is the impulse in the soul of the New Jersey teenager, one who just wants to be scared for a moment, to feel a danger that simple suburban life can’t offer, and you can have that on a late night joyride through Clinton Road and still you’d be home by curfew.

But right when I had given up, thinking I was no better than the teens in SUVs bumping bumpers with other teens in SUVs, the most haunting and unexpected thing that has ever happened on Clinton Road happened to me right then and there. I was filled suddenly with an overwhelming love for New Jersey—for the roads and the hauntings, and the people talking about humidity. This place that just wants to be special; its people who just want to be remembered. Who could argue with that? Who could not get behind that? The ghosts and the people all fighting to be heard and fighting to be loved. I would love them all. I would love it here. I would stop thinking of New Jersey as a satellite office for New York. I would take it on its own terms and I would be its daughter.

I turned around and I took one last ride, this time alone, down Clinton Road. It was even less foreboding that it had been before. Yes, a road is just a road. A state is just a state. A place is just a place, unless you decide differently, unless you absolutely need it to be something else. And you and I are just people who still believe that we are alive.

This story was funded with support by Longreads Members. Join, or make a one-time contribution.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook