Here Are the Medals Given to Eugenically Healthy Humans in the 1920s

People were judged alongside livestock at state fairs.

A Fitter Family medal. (Photo: David Plotz)

On August 17, 1920, the Topeka Daily Capital reported an exciting development: a new class of competition had been added to the livestock judging categories at the Kansas Free Fair. Class 2.603, part of the Division 203, “Human Stock,” allowed families to submit themselves for judging by the fair’s eugenics department. If they were deemed the most pleasing specimens at the fair, they would win the title of “Fitter Family.”

Though the category was new, the judging of humans according to the principles of eugenics wasn’t a novel concept in 1920. For at least a decade, state fairs across America had been holding “Better Baby” competitions, in which infants were examined, measured, compared to growth charts, and awarded trophies for good health and genetic superiority. University of Michigan history professor Martin S. Pernick writes that such contests “rivaled livestock breeding and hybrid corn exhibits in popularity.”

Fitter Family competitions, which spread from Kansas across America during the 1920s, were an extension of the Better Babies idea. The advantage of examining older children and adults was that, unlike babies, these specimens could talk back. They also had more life experience for judges to draw upon when making their evaluations.

For every family, representatives from the Eugenics Society of the United States of America would fill out the Fitter Families Examination form. The required details for each family member included their date and place of birth, any serious illnesses, their education, occupation, “physical, mental or temperamental defects,” and “special talents, gifts, tastes, or superior qualities.”

The whole judging process lasted about three-and-a-half hours, and took place in the fair’s Eugenics Building. Tacked onto the walls were posters declaring that within three generations, careful breeding could eliminate “unfit human traits” such as feeblemindedness, criminality, pauperism, and epilepsy.

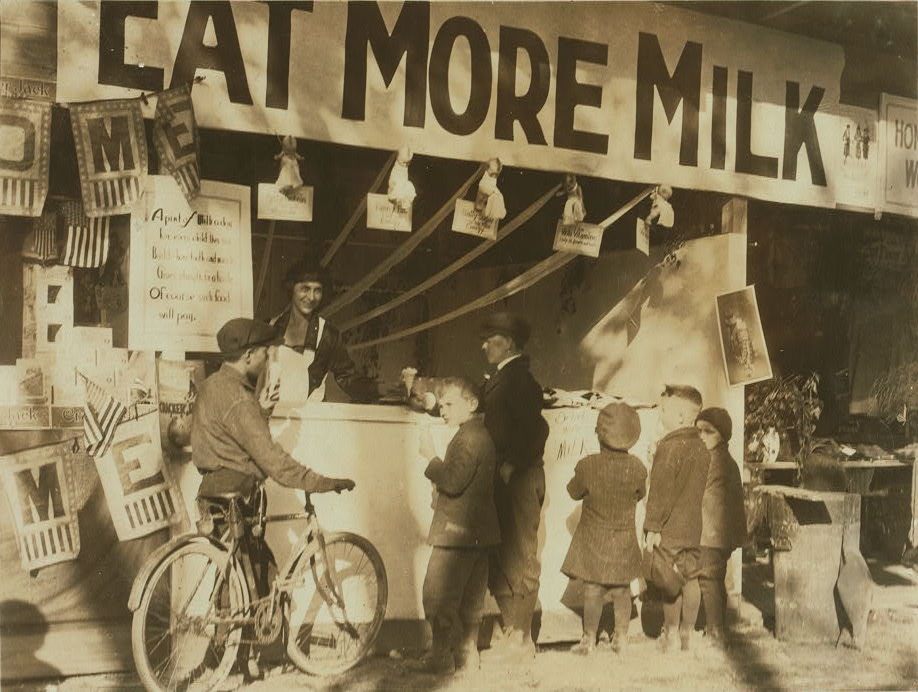

Attendees at a West Virginia fair in 1921. Fitter Family contestants who did not win medals were sometimes encouraged to drink more milk and try again next year. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-nclc-04435)

Entrants supplied blood and urine samples, had their height and weight measured, took an IQ test, and answered a battery of questions about their daily habits, medical history, and social behavior. After all these tests had been taken and results logged, each family member received a letter grade.

Anyone scoring a B+ or better was given a bronze medal bearing the phrase “Yea, I have a goodly heritage.” This phrase was swiped from Psalm 16:6—the full sentence is, “The lines are fallen unto me in pleasant places; yea, I have a goodly heritage.”

Though the Better Baby and Fitter Family contests attracted their fair share of gawkers, and the trophies and medals added flair, the competitions weren’t intended as entertainment. Public health workers used the baby contests as a way of disseminating medical information to parents at a time when infant mortality was of greater concern. Similarly, the American Eugenics Society sponsored the Fitter Family contests in order to collect genetic data for research and spread the gospel of careful, considered breeding.

Fitter Family contests were nominally open to any state resident, but York University history professor Molly Ladd-Taylor writes that competitors “were almost always white, native-born, Protestant, educated, and from a rural background; they had no family member with a congenital disability and surely already considered themselves to be fit.”

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook