Haunted Houses Have Nothing on Lighthouses

From drowning to murders to the mental toll of isolation, these stoic towers carry a full share of tragedy.

Though they shared a name, it’s said the two lighthouse keepers, the towering Thomas Griffith and the middle-aged Thomas Howell, didn’t get along, and could empty pubs with one of their heated arguments. In the winter of 1800 to 1801, the two men were stuck on the most remote island in Wales, 20 miles from shore, operating Smalls Lighthouse. The brutal winter weather turned what should’ve been a month-long stay into a grueling, almost five-month exile. Then, four months into their stay, things got worse. Griffith took ill, according to Ivor Emlyn’s 1858 account, or perhaps he fell, as Christopher P. Nicholson writes in Rock Lighthouses of Britain. Howell hoisted up a distress flag (likely an inverted Union Jack), but no help came. After weeks of suffering, Griffith died.

For the next three weeks, Howell’s only companion was Griffith’s rotting corpse. He feared that casting the body into the sea would implicate him in Griffith’s death. After all, everyone knew they didn’t get along. So Howell, trained as a woodworker, assembled a makeshift coffin for his departed colleague and secured it to the lighthouse’s railings. After three weeks, a massive sea swell tore the coffin apart, scattering Griffith’s remains across the beach. Howell again secured Griffith’s body the best he could, this time to the outside gallery.

Ship after ship attempted to land on the island to relieve the desperate keepers, with no knowledge that only one remained. According to Nicholson, one ship managed to get close enough to see “a man leaning motionless on the gallery next to the flag of distress, his hand waving freely as if trying to attract attention.” Unable to dock, the ship took home the news that the keepers were managing. The light was still lit, after all. The ship’s captain didn’t realize the hand flopping in the wind belonged to a dead man.

During a brief reprieve from the storms, a boat from nearby Milford made another attempt. When it successfully arrived, the sailors were overtaken by the smell of rot. Then Howell emerged, seemingly more dead than alive, an unrecognizable shell of a man.

Lighthouses are full of stories like Howell and Griffith’s—death, isolation, madness, and in some cases actual murder. While their light can be a beacon of hope to lost sailors, darkness has often haunted them. Almost every one seems to have a few ghostly inhabitants. As Dick Moehl, former president of the Great Lakes Lighthouse Keepers Association, told Dianna Stampfler in her book, Michigan’s Haunted Lighthouses, “every lighthouse worth a grain of salt has a good ghost story.” Old Victorian mansions have nothing on them.

The earliest known lighthouse was one of the wonders of the ancient world, Pharos of Alexandria. Construction began some time before 270 B.C., and Pharos lit the Mediterranean for almost a millennium. With a 300-square-foot base, it is estimated to have been 400 feet tall. The Roman Empire would go on to build something like 30 lighthouses around the Mediterranean and Europe’s Atlantic Coast. But after the fifth century or so, lighthouses disappeared from the architectural record until the later Middle Ages and early Renaissance. One of the earliest of these was the Meloria lighthouse, off the coast of Tuscany, built in 1157. Soon other coastal countries—Spain, France, Portugal, England—started constructing lighthouses, too.

The century between 1840 and 1940 is largely considered to be the golden age of the modern lighthouse. In the United States alone, the number of lighthouses went from 16 to roughly 1,500 during this time. The rest of the world, especially Europe and its colonies, also went through a lighthouse-building frenzy, but nowhere else reached the heights that America did.

Kevin Blake, a geographer at Kansas State University who has written about lighthouses, says that the buildings appeal to Americans’ “rugged individualism” and “pioneer spirit.” They represent a frontier and the spirit of survival—one keeper facing the odds, weathering the seas and storms, with self-sufficiency and grit. Keepers were often veterans, which added to the heroic air the job carried, according to Blake.

There’s also an aura of “mystery associated with lighthouses,” he says. As superior navigation equipment began to replace lighthouses and automated lighting systems began to replace the keepers for the ones that remained, “this slow loss of change, this sense that America was losing something unique, is when ghost stories came in.”

Michigan, with 129, has more lighthouses than any other state. Many of those lighthouses, says Stampfler, have a ghost story or two. A lighthouse is like a “safety port” for ghosts, she says, and spirits of “keepers, ship captains, sailors—they all can become residual spirits,” drawn, as you might expect, to the light.

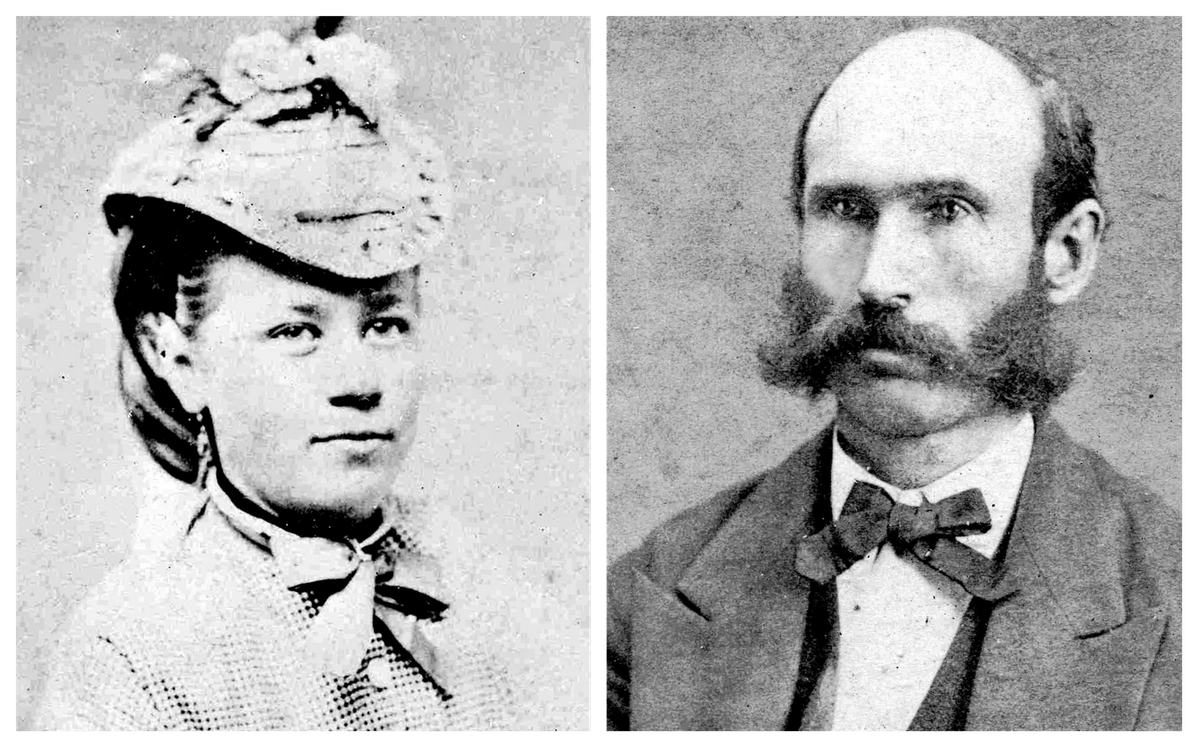

One tragic story that has always fascinated Stampfler comes from South Manitou Island Lighthouse, on a small, sleepy island about 45 miles northwest of Traverse City. Between 1866 and 1878, Civil War veteran Aaron Sheridan and his new bride Julia operated the lighthouse. Julia was officially recognized as the lighthouse’s assistant keeper in 1871 (along with many other women who worked both as keepers and assistant keepers—even today). Over the course of 12 years there, the couple had six sons.

Then, on March 15, 1878, Aaron, Julia, and their youngest son Robert were returning from the Michigan mainland with the help of a local sailor named Christ Ancharson. The waters were calm until they neared the lighthouse and “the wind went down and one of the old seas capsized the boat,” Ancharson said later. The minutes ticked by as Christ, Aaron, Julia, and little Robert clung to the overturned boat, screaming for help. Baby Robert was the first to go, dying in Julia’s arms. Then, Aaron and Julia, too, slipped beneath the waves. Only Ancharson survived, after four and a half hours holding on to the slippery hull.

The bodies of the family never washed ashore, but their ghosts, according to legend, still haunt the remote lighthouse. “Visitors have reported hearing the echo of voices, the sounds of footsteps and other unexplained noises coming from the causeway, which connects the boarded-up keeper’s residence to the light tower,” writes Stampfler. Stampfler herself even visited the lighthouse and spent “time slowly climbing the tower and listening for the cries of the Sheridans,” without success, she says.

The deaths of Julia, Aaron, and Robert isn’t the end of the Sheridan family’s tragic tale. In 1893, the eldest son Levi, or “Fisk,” as he liked to be called, died during the collapse of the “Big Four” railroad bridge near Louisville, Kentucky. George, the next oldest, spent months trying to recover Levi’s body, but his brother was never found. George, following in his parents’ footsteps, became a lighthouse keeper. For decades, he struggled with depression, often leaving his keeper duties to his wife Sarah. In early spring 1915, George was visiting his uncle, another keeper, at Grosse Point Lighthouse in Illinois. Several days later, on March 24, 1915, George’s body was found hanging from the rafters, an apparent suicide.

There’s a duality to lighthouses, says Stampfler, because “Here you have a light full of darkness.” Stampfler sees many similar examples in lighthouse histories. She can cite numerous lighthouses that bear the weight of unexplained death, suicide, madness, or murder.

In 1960, a well-reported murder took place at Little Ross Island Lighthouse off the southwest coast of Scotland. It all began with a father and son’s day trip to the island. It was a trip the Collins had made many times before, but when they arrived on the small island on Thursday, August 18, things straight away felt weird. Usually, the keepers would greet them as they disembarked, but that day the island was eerily quiet. After hearing a phone call go unanswered, “my father eventually plucked up courage and went into one of the houses,” David Collin, an architecture student at the time, told the BBC. “He quickly came running out and said, ‘Get help if you can, there is a man ill in his bed.’” After the authorities arrived, it became clear that the middle-aged lighthouse keeper Hugh Clark had been shot at close range with a .22 rifle. There was only one man the evidence pointed to, Robert Dickson, the assistant keeper. Having fled the island, Dickson was the subject of a manhunt before he was arrested in Yorkshire. The trial captured national headlines and Dickson was sentenced to death (later reduced to life in prison). He didn’t stay incarcerated long. Two years into his sentence, Dickson killed himself.

For Blake, there’s always been something “sublime” and “dangerous” about lighthouses. “When you climb a lighthouse and you step onto that parapet or gallery that may be 110, 160, 200 feet above the Earth’s surface, it’s practically a death-defying experience.” Indeed, there are stories of keepers “throwing themselves off lighthouses,” says Blake, isolation having driven them to madness.

When people think of a haunted house, a towering lighthouse on some rocky coastal bluff might not be the first thing that comes to mind. And yet it seems that almost every lighthouse bears the weight of some tragic tale. The isolation, harsh conditions, and constant work were too much for many of the people charged with keeping those lights glowing, through listless nights and unrelenting storms. Perhaps it’s time crumbling Victorian mansions made way for a different kind of haunted house, one that has always lighted the way for both the living and the dead.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook