The Secret History of Panamá’s Most Colorful Clothes

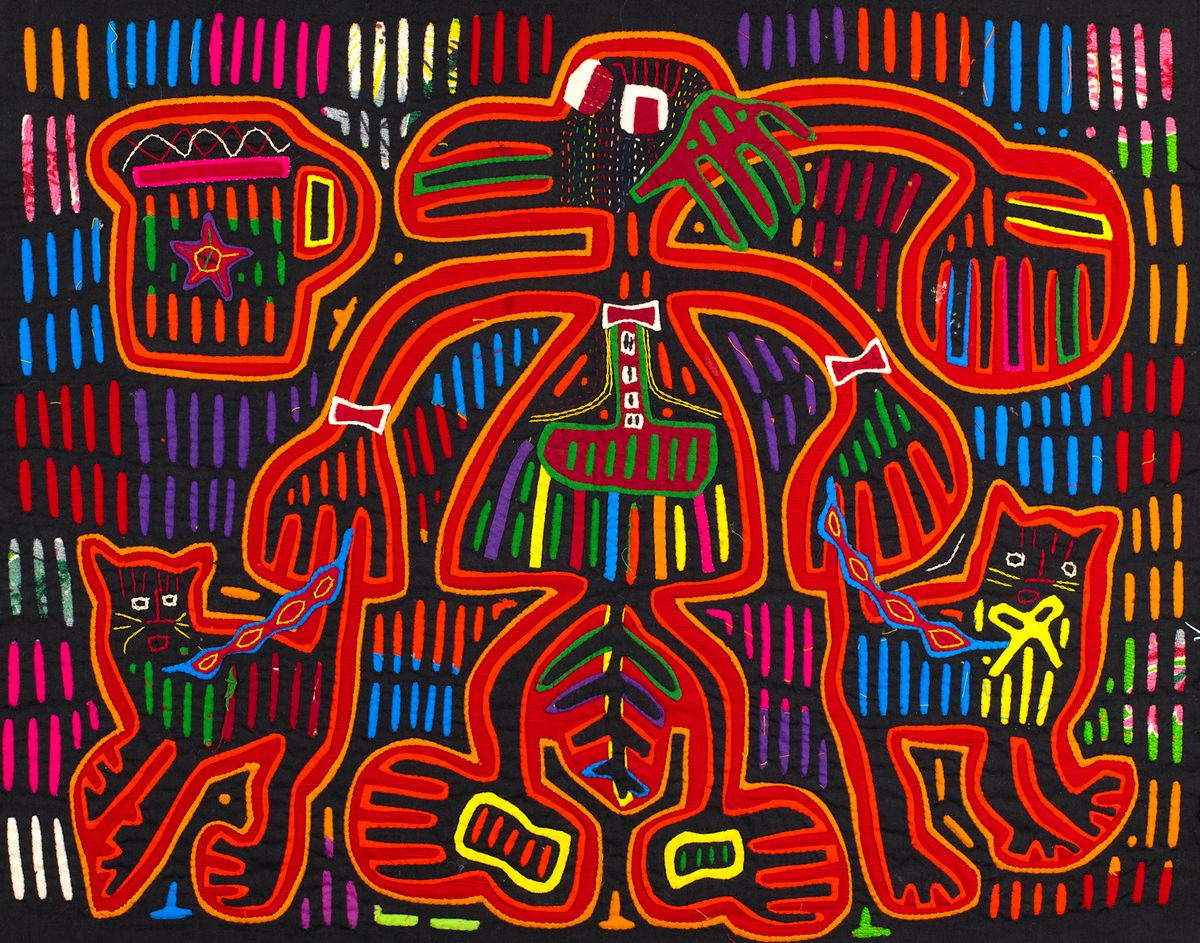

In Guna Yala, indigenous women sew stories of legend, revolution, and even Minnie Mouse into the elaborate textiles known as molas.

In the crystalline waters of the Caribbean, far from the skyscrapers and traffic of Panamá City, is a tiny, 365-island archipelago known as Guna Yala, or the San Blas Islands. Today, around 50,000 Guna people are dispersed across 49 island communities there. An indigenous people from what is now Panamá and Colombia, the Guna live today much like they have for generations. Life is mostly spent outside, with only hammocks for sleeping beside palm frond–covered wooden homes. In Guna Yala, a politically independent territory, the whole community weighs in on legal and political decisions. And it’s the women who run the show. They inherit land and possessions. Grooms move into the brides’ home and take their names. And it’s the women who create, wear, and sell elaborate, colorful molas, an enduring symbol of Guna independence.

Molas are hand-sewn cotton textiles traditionally fashioned into blouses and worn by Guna women. They often sport vibrant, geometric designs that range from abstract patterns to intricate renderings of legends. Today, the textiles are reworked into pillows, wall hangings, bedspreads, and even headbands.

Molas are made using “reverse appliqué on several layers of cotton fabric,” says Rita Smith, owner of Rita Smith Molas Gallery. “It’s almost like when you’re making a sandwich,” she says. “Some require two layers, but some require more than two.” Once the fabrics are layered, the artist cuts away the top layer in a specific pattern to reveal the color beneath, and then sews along the edge of the cutout to secure the design. The artist repeats this again and again to form the design, a process that can take months. The technique has been passed down from mother to daughter for generations.

Mola designs vary widely. “Some [molas] are mythologies, some may be medicinal plants, some may have histories,” says Smith. Giovanna Puerta, another mola seller based in Panamá, has seen examples with designs based on artists’ dreams, plants, animals, and religious subjects, including one mola depicting an intricate illustration of the biblical story of Solomon proposing cutting a baby in half: “How impressive is that!” More recently, Guna women have begun creating designs based on pop culture to cater to tourists. Think a Spider-Man mola or a Minnie Mouse facemask.

Molas haven’t always been a part of Guna culture, says Andrea Vázquez de Arthur, the curator of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s current exhibition, Fashioning Identity: Mola Textiles of Panamá. “[The Guna] were originally from the inland rainforests of Colombia and were relocated to their current coastal territory during the colonial period,” between the 16th and 19th century, says Vázquez de Arthur. While living in the rainforest, “They didn’t really wear much clothing because that’s just not an environment where clothing is your friend,” she adds. “What you want is bug repellent so they would paint their bodies” with ink, possibly derived from tree sap, that acted as a natural deterrent.

When the Guna migrated to the coast, where there is wind and sun, “Suddenly it’s a different story and clothing becomes more important,” says Vázquez de Arthur. Influenced by European immigrants and traders, Guna men started making their own Western-style clothing. Guna women, however, drew inspiration from Guna body paint designs and “invented their own style of dress.”

By the late 1800s, Guna women proudly wore handmade mola panel blouses and geometric wrap skirts, at least until 1918, when the Panamánian government made wearing molas illegal, along with speaking the Guna language and various other Guna spiritual and cultural practices. Panamá’s president at the time, Belisario Porras, wanted “to specifically eradicate Guna culture and assimilate them into the general Panamánian population,” says Vázquez de Arthur. Guna villages became police states. “Just making and wearing molas became an act of political protest,” she adds, and they “became a very visible symbol for their push to have their own rights.”

After years of quiet resistance, the Guna finally revolted on Carnival, February 23, 1925. They kicked the police out of their communities and declared independence. American ethnologist Richard Oglesby Marsh wrote the Guna’s 25-page declaration of independence, after having befriended them while studying their higher-than-average albino population. (He even brought three Guna albino children and five adults on a very publicized trip to the United States.) Over the next few days, 30 police officers and several Guna, including children, died in the crossfire of the conflict. That’s when American diplomat John Glover South stepped in and helped broker a peace agreement.

Today, Guna Yala continues to operate as an independent territory or comarca. They have representatives in the Panamánian government, but their own laws. Panamánians have to show a passport to travel to the islands.

Molas persist as an enduring symbol of Guna independence. Their importance “calls attention to how much of an impact women have in [Guna] society,” says Vázquez de Arthur. But both Smith and Puerta worry molas could die out if artisans aren’t adequately supported. “The mola doesn’t get the respect it should, because each mola takes about 30 hours,” says Puerta, and sometimes artists can earn as little as $5 for their efforts.

Since the 1980s, commercial mola imitations have threatened the Guna’s own mola economy. Several laws have been passed in Panamá banning the fakery, but mola artists still face an uncertain future. “There may be one day when the younger generation may just not be interested in making molas,” Smith says. It’s no longer uncommon to see cell phones or Guna women in Western dress on the islands. But for now, artists continue to spin Guna legends and dreams into beautiful molas and, as an ethical reseller, Puerta says, “That’s what I can help with—helping the artisans.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook