The Dark and Fabulous Dinner Parties of the First Professional Food Critic

Grimod de La Reynière hosted his own funeral.

The invitations were almost as large as they were bleak. Printed on black-rimmed paper almost two feet in length, they bore troubling news: “Madame Grimod de La Reynière is humbled to inform you of the recent painful loss of her husband. The funeral will take place today, Tuesday July 7th. A convoy will depart for the mortuary from 8 rue des Champs-Élysées, at 4 p.m. precisely.” (The year was 1812.)

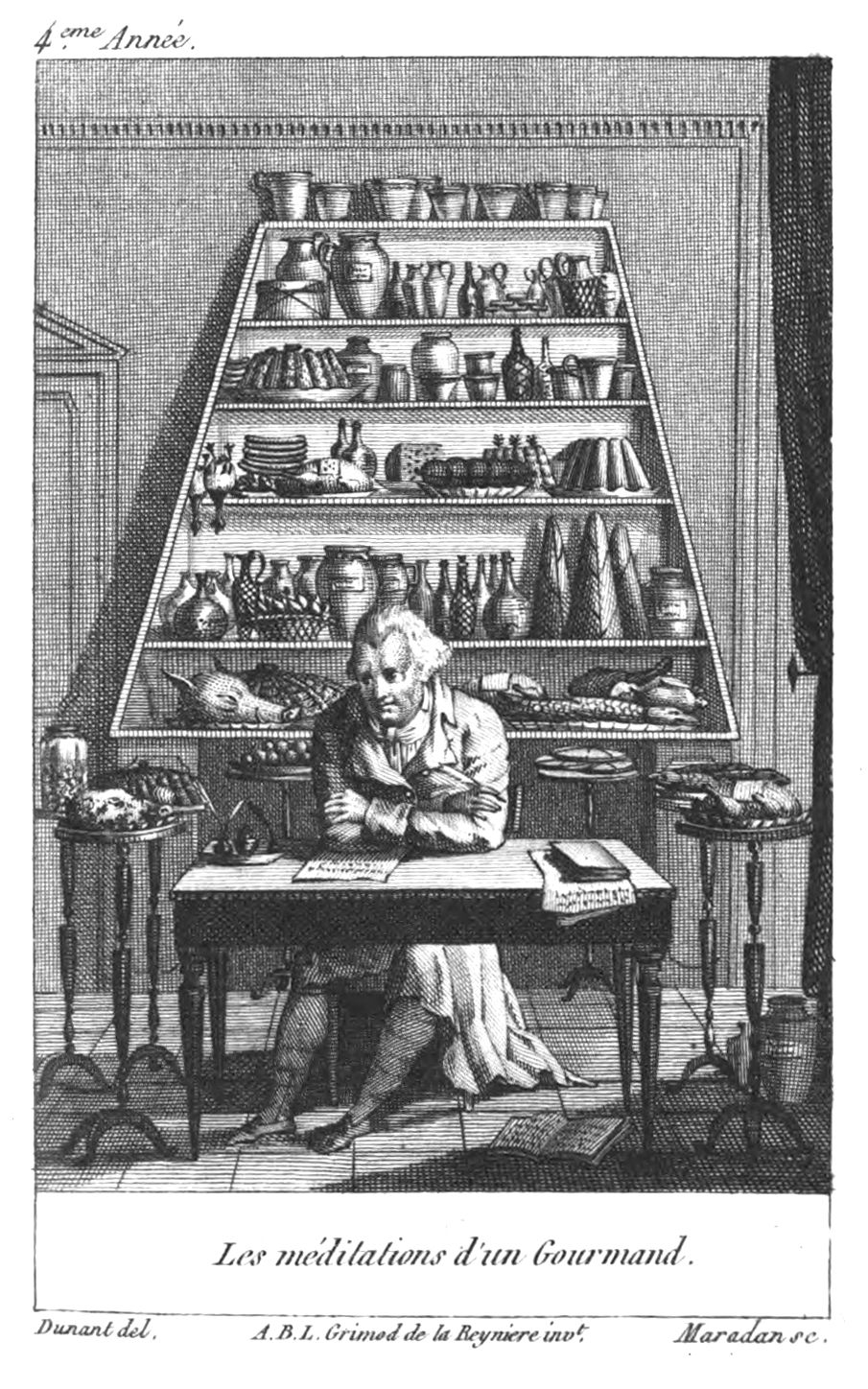

It must have seemed at first shocking, and then enormously odd. Parisian high society was aghast: The dead man, Alexandre Balthazar Laurent Grimod de La Reynière, had not been ill, nor especially old. Announcing a funeral for the very same day was exceptionally unusual. And that 4 p.m. departure (at dinner time!) must also have seemed strange. Grimod was well known in Paris as the author of Almanach des Gourmands, an eight-volume series of the world’s first restaurant guides, and would have hated to deprive his friends of a hot evening meal.

In light of these sacrifices, the ranks of faithful friends who showed up to pay their respects were allegedly thin. Inside the house, which was draped with black, the coffin sat lugubriously, illuminated by two rows of torches. A hearse waited nearby. The guests stood around, and as they waited, described the many virtues of their departed friend. There was plenty to draw from: Grimod was perhaps the world’s first food critic, dedicated to the art of gastronomy. He was impossibly clever, with a wicked sense of humor, and had trained as a lawyer. But an unexpected noise silenced the party. Two doors flung open, revealing a long table laden with food and lit by hundreds of candles. At its head sat a smiling Grimod. He looked at the mourners and said: “Dinner is served.”

Astonished, they made their way to the table where, as the story goes, there was precisely the right number of places. Still recovering from their shock, the friends struggled to make headway on the dishes as they expressed their relief. These compliments were cut short by the host, who implored them to eat before the meal got cold.

Later in the night, Grimod revealed why he had gathered them in this way: “I wanted to know who my real friends were—there’s no better way to test that than to see who would come to my funeral, even if it meant missing dinner.”

Grimod grew up in lavish surroundings. The son of a wealthy Parisian tax collector, whom he despised, he had a rare condition that deformed his fingers and led his parents to keep him out of sight as a child. Perhaps fearing the implication it might have about their genetic diversity or the strength of their bloodline, they told their friends that he had fallen into a pigpen as a small child, and has his hands eaten by hogs. For the rest of his life, Grimod wore ingenious metal prostheses, concealed beneath white gloves.

Throughout his twenties, he studied to become a lawyer and dabbled in theater critique, swanning between salons and soirées. “His louche lifestyle and republican politics infuriated his parents,” writes the culinary historian Cathy Kaufman, “as did his refusal to conform to social expectations by surrendering his law practice for the higher status position of magistrate.” After he graduated, he refused to be a judge and instead did pro bono work for people struggling with tax law. “As a judge,” he is said to have to have remarked, “I could find myself in the position of having to hang my father, while as an advocate, I would always be able to defend him.”

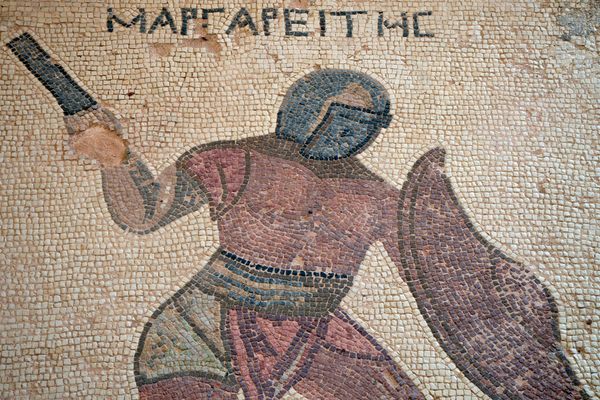

Though he may have practiced as a solicitor, his heart lay in the theater. And so, in February 1783, when his parents were out of town, he hosted a first morbid dinner party at their home. The family was extremely wealthy and lived in a grand house overlooking the Champs-Elysées. “[It] was famous for its wall panels, executed by the painter Charles-Louis Clérisseau and inspired by frescoes from the recently discovered cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum,” writes Kaufman. “The house was excruciatingly chic.” It was to this address that 300 funerary-themed invitations directed Parisian high society.

But when they arrived, most were shunted to one side. Barely two dozen were allowed to progress through to a checkpoint: Were they there to see Monsieur de la Reynière, “the defender of the people,” or the other Monsieur de la Reynière, “the oppressor of the people”? (Grimod’s father, it was implied, was the latter.) Those who answered correctly were led into the banquet hall itself, lit as bright as daytime by 365 lamps. A decorative coffin was behind every seat; and a catafalque, or coffin stand, sat upon the table. “This funereal theme was designed to poke fun at Grimod’s mother,” writes Carolyn Purnell, in her history of the Enlightenment. (She had failed to mourn the death of a woman who was allegedly one of her best friends.)

The hundreds of guests who had not been permitted to approach the checkpoint, let alone the banquet hall, watched from a balcony as Grimod’s chosen few dined. They were not permitted to leave, nor served a proper meal, but instructed to stay on the balcony and observe, with only a few biscuits provided to sustain them. Meanwhile, down below, Grimod treated his guests to coffee, liqueurs, and a magic lantern show.

Understandably, people were livid. One is said to have shouted from the balcony: “They will send you to the madhouse, and strike you from the list of members of the Bar.” Grimod became the talk of the town, holding other such parties while his parents were away: At one, guests were served only black foods (truffles, chocolate, plums, caviar); at another, a live pig was positioned in Grimod’s father’s chair, dressed in his clothes. It’s not entirely clear how often these dinner parties were held, or whether it was over one sustained absence. Eventually, though, his parents had enough of their son’s antics. The young man—he was about 25 at the time—was banished to a monastery in the countryside for two years.

In the monastery, he learned to appreciate what was on the table almost as much as he’d enjoyed the presentation. According to Kaufman, “He dined well, if less colorfully, with the monks, and without an audience for his subversive games, Grimod began to study the arts of the table, rather than the table as art.” Later, he would travel around France, gaining an appreciation for the distinctions between Lyonnais, Provençal and Alsatian cuisines.

When Grimod returned to Paris after his father’s death, he found the family’s finances in ruins. Eventually, he parlayed his enthusiasm for gastronomy into a living. Paris’s social ranks were shifting, and restaurants were full of upwardly ascendant people who—so far as he could tell—knew nothing about the art of fine dining. Capitalizing on what he perceived as a growing desire for an accessible, reliable guide to the gastronomic arts, he began his first book of restaurant reviews and culinary critique in 1803. Over the next nine years, he wrote seven more, which sold tens of thousands of copies apiece.

His glittering career as a food critic began with these inauspicious dinner parties. The one for his faked death, however, marked the end of a fabulous and extraordinary public life. In 1812, after hosting his own funeral, Grimod and his wife retired to the countryside, and from Parisian society, for good.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook