The Man Searching the World for Artifacts Bearing His Name

Why an artist named Glen Eden collects “Glen Eden” memorabilia.

On a 2002 trip to San Diego, the artist Glen Eden Einbinder took a detour to visit America’s largest member-owned nudist resort and club. He wasn’t there as a member, nor as an aspiring nudist. “I was a little nervous of what to tell them,” he remembers. “So I didn’t tell them what I was doing. I just said that I was interested in the place, and if they had any information.”

He turned down a nude tour (“I’m not a prude, but I felt a little uncomfortable doing that, as a single man,” he says, laughing) and instead left with a few pamphlets about this “Nudist Resort For All Seasons.” Outside, he snapped a few shots of the signage and surrounding streets, before heading on his way.

In fact, Einbinder was there as a collector. For over 25 years, he’s amassed a treasure trove of objects that somehow incorporate his first and middle name. (The nudist resort in Corona, California, was the Glen Eden Sun Club.) Over the decades, he’s made his way to Grayson County, Texas, to visit the site of the Glen Eden plantation; to the Glen Eden Pilot Park, in Raleigh, North Carolina; and to the corporate headquarters of the Glen Eden Wool Company, in Georgia, to name just a few of his stops. Sometimes he explains why he’s there; on other occasions, he’ll gloss over the truth, fearing a negative reaction. “I’m shy with a lot of things like that,” he says, faltering.

From each place, he’s acquired objects: leaflets, photographs, a square of mottled carpet the color of moss. But not everything in his collection is the product of a journey. Some, like postcards from motels that no longer exist, are bought on eBay. Others are gifts from friends. A New Zealand suburb is represented by a map and a leaflet containing a bus route. Many of these places have been shored up from elaborate searches on Google Images. It’s at once art project and hobby, an odyssey across places real and forgotten.

Einbinder’s parents didn’t name him for a place. Glen, he says, is somehow related to the initials of his ancestors, with the “G” perhaps coming from a Great-Aunt Gussie. And Eden comes from the Jack London book Martin Eden, which his father was reading when Einbinder was born. Though the two together conjure up some pleasant idyll—Glen as a woodland valley, Eden as a garden—he didn’t realize the connection until he started to come across the huge volume of places that share his name.

In person, Einbinder is soft-spoken and self-effacing, with thick, sooty eyelashes and an open smile. He’s small and dark, a little androgynous, and lives alone in a neat, one-bedroom apartment near Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. A piece of his own art, a woodwork of a bower bird’s nest and collection, hangs on the wall. After years of work at the Brooklyn Children’s Museum, as their Chief Engineer of Exhibits, he now freelances in museums across New York City, helping to design and execute exhibits and environments.

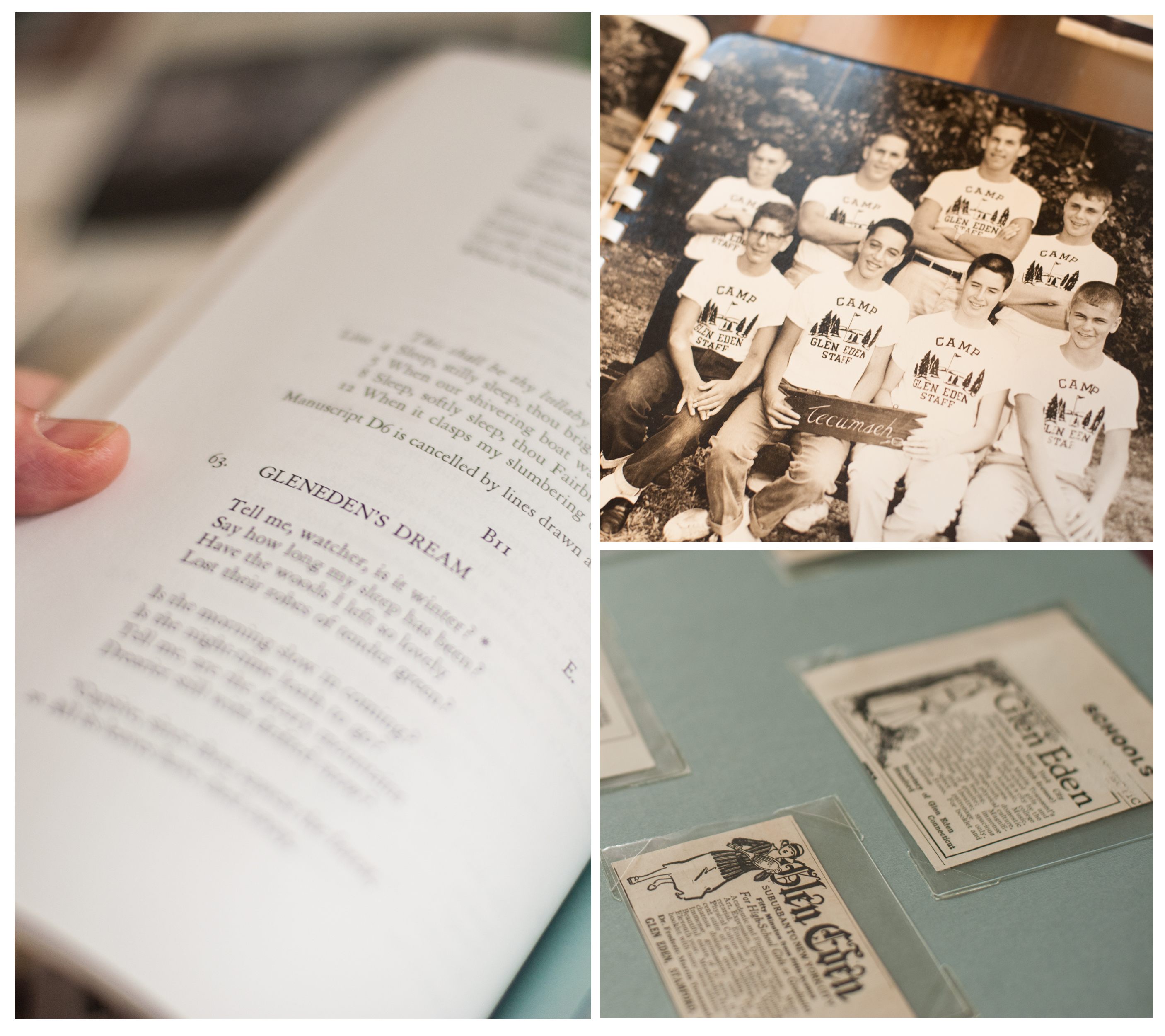

You can see that curatorial spirit in how he cares for his collection. For a recent show at the City Reliquary’s Collectors Night, Einbinder stuck a grid of plastic rectangles onto a piece of blue card, then slipped a vintage postcard into each sleeve. Seven metal milk bottle tops, from a Glen Eden dairy, are as shiny and pristine as if they’d been delivered to his doorstop yesterday. There are many more objects, each as fastidiously preserved, such as nine pieces of Glen Eden-branded hotel soap paraphernalia or a ceramic jug. One of his favorites is a framed gouache painting of a woman with ice-skates flung over one shoulder. Her sweater reads “Glen Eden,” likely for a girls’ boarding school in Poughkeepsie, New York.

That’s on top of teacups, clothing, books, drink coasters, leaflets, and dozens of other paper items, including photographs of street signs from places he’s visited, all featuring his name in some manner. He’s not in the photos, though in some, his shadow creeps into the frame.

There are rules to this collecting, but even now, he’s still trying to figure out exactly what they are. The names have to be in the right order—a spoon marked “Eden Glen” doesn’t really count, though he keeps it nonetheless. Digital objects don’t either, unless he finds a way to make them exist in physical space. He gives the example of a vividly colored label from a can of peaches, which he saw on eBay. He lost the auction, but saved the digital image from the listing. As a collection of pixels, it’s only an addendum to the main collection, he says, though if he decided to print it out, or even glue it to a can, it would count.

He is still hashing out other guidelines, he says, like whether a series of Emily Brontë poems addressed to a mysterious R. Gleneden are valid additions. “It feels like it’s not specific,” he says, holding the book open. “A person is harder. Because I’m the person—so if there’s others, it doesn’t work for the collection.”

It all started with a bottle of whisky. As a student in Valencia, California, Einbinder came across a bottle of now-defunct Glen Eden single malt. (Online reviews describe it as “vile” and “repulsive.”) When the bottle was empty, he threw it out, but held on to the red, gold, and black label. At the time, he says, he was going through a phase of collecting things he came across that somehow spoke to him, often from another time: “I was going to thrift stores, and picking up records for 50 cents, just because of the way it looked.” Next, he came across a classified advertisement for the Sun Club in the back pages of a newspaper. He cut it out and kept it. From there, the collection blossomed, and then ballooned.

But pinpointing exactly why Einbinder does it is even harder than choosing concrete rules to govern the cache of artifacts. “The ‘why’ is not really apparent. It’s just kind of fun, I think.” He gives the example of people buying souvenir mugs and keyrings that are emblazoned with their first name. There’s no actual connection, he says, yet somehow people are still drawn to things that arbitrarily have their names on them. “In terms of what that says about me, I think I like ‘arbitrary,’” he says. In terms of what it means as art, he’s even less sure. Friends have asked him if it’s self-portraiture—if the collection of objects together somehow represents him, or says something about him as a person. But beyond the fact that “all the things are together, and they’re interconnected through me,” there’s little to be gleaned about the collector himself.

Rather than worrying about why he does it or what it represents, he says, the next step is making it accessible to those who might want to see it, and finding a digital home for these physical things. Hundreds of digital photographs are meticulously stored on his laptop: Online, they might finally be a valuable addition to the archive, whether displayed separately or enmeshed among photographs of the things he already has. “It would be a lot,” he says, “but I would like to do that.”

And in the meantime, he’ll continue to collect, buying old postcards from eBay and checking Google to see whether other Glen Edens he may not have known about have suddenly made their way onto the internet. He’d like to find the time and resources, too, to make it to the sites of places memorialized in his collection, such as the long defunct Glen Eden Hotel, in Chicago, or Camp Glen Eden, a former boys’ summer camp in Eagle River, Wisconsin. Each one opens up a new, forgotten world, with its characters and its history—a collection not just of things, but of stories, each linked by a common name.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook