Glacier Research Is Particularly Treacherous at the ‘Third Pole’

Scientists in the Indian Himalayas deal with low oxygen, zip lines, and paths blocked by giant boulders.

At least twice a year, Dr Parmanand Sharma embarks on a multi-hour, potentially treacherous commute to work—by car, foot, and zip line. To reach his version of the office, he takes the Manali-Leh Highway; an expanse of road that winds through the Indian Himalayas, ascending from 6,000 feet to 17,000 feet. At that height, Sharma’s closing in on the Himalayan Cryosphere or “the Third Pole,” an epithet for the largest mass of ice outside the polar region. It’s this frozen terrain that Sharma is here for; specifically, its glaciers.

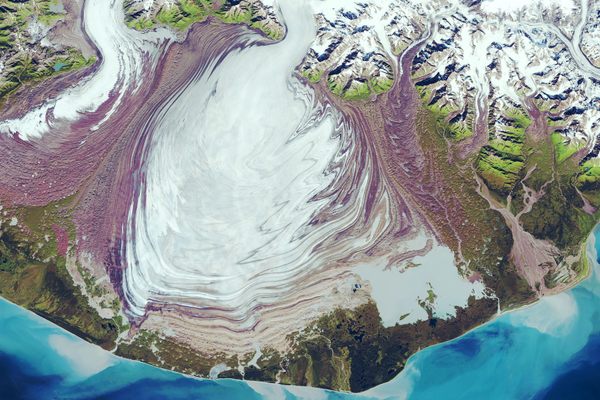

“Climate change is altering the glaciers in the Hindu Kush Himalayas (HKH),” says Sharma, 48, a glaciologist with India’s National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR). “We haven’t even scratched the surface in understanding how fast the glaciers are melting and what happens next.” Over 1.6 billion people depend on the 19 rivers emerging from the 2,175-mile-long HKH and recent studies show a third of the glaciers are in danger.

Unlike the many thrill-seeking tourists who take this route, Sharma is heading straight for Himansh, a research station located at an altitude of 13,000 feet in the Chandra Basin. This basin feeds the Indus river, which gets nearly 80 percent of its water from HKH. Nearly 250 million people live in the Indus Basin alone.

“We have been looking at six glaciers, which had a total area of 115.8 square miles in 2009. In 2019, it was only 86.9 square miles,” says Sharma. “There’s thousands of glaciers like these.”

“Our aim is to study the response of the third pole to climate change, and its hydrological impact,” says Dr Thamban Meloth, 50, head of NCPOR’s polar science department. Meloth also spearheaded the center’s foray into the third pole in 2013.

Sharma, who heads NCPOR’s Himalayan Cryospheric Studies program, studies the mass balance of glaciers to examine the accumulation and loss of water; essentially “budgeting” how much water comes and goes. He does so with the help of a network of insulated bamboo sticks fixed at various spots across the glacier to measure the level of ice and snow over time.

Reaching the glaciers isn’t for the faint hearted. Alpine trees of the outer Himalayas vanish as the weathered “highway” enters the cold desert of Lahaul-Spiti. At 13,000 feet the air thins, the oxygen level around 41 percent less than at sea level. A few memorials for deceased motorists, endless ranges, and ravines keep you company for the 77 miles to Himansh. The path is often blocked by large boulders jettisoned down the mountains by the violent energy of snow-melt waterfalls. At Batal, the last motorable point along the Manali-to-Kaza road, the easiest part of Sharma’s journey ends.

From here the scientists trek for nearly four miles, or use a zip line going over the Chandra river to reach the station. Distance is measured in time and the process can take four to five hours for the uninitiated.

Scientists say studying the Himalayan glaciers can help inform water management, policy, and infrastructural changes that could save millions of lives. So why isn’t there more widespread and rigorous research on the Himalayas?

“Systematic studies (continuous monitoring for 10-30 years) in this region are difficult due to logistical hurdles,” Sharma, who visits the Arctic region and the Himalayas every year, explains.

The challenging terrain combined with geo-political interests (the HKH crosses over eight countries) makes it impossible to carry out sustained research, resulting in gaps in data. For instance, there are 9,575 glaciers in the Indian Himalayas as per the Geological Survey, but the Indian Space Research Organisation puts the number at over 32,392. The area itself varies from 17,345.6 square miles to 14,478.9 square miles, depending on who you consult.

Kamini Meshram, pursuing a doctorate in geochemistry of glaciers at NCPOR, made her maiden voyage to the third pole in 2019. “The lack of oxygen and the dangerously steep slopes was a huge problem,” she says. “You feel giddy and nauseous. Your legs don’t move at times. Things appear closer than they are in the Himalayas.”

“Most research students never come back after the first visit,” says Sharma. But Meshram is among the few who can’t wait to return.

Stations like Himansh, established by NCPOR in 2016, become the backbone of long-term monitoring projects. Himansh comprises three white huts made of prefabricated insulated materials and encircled by a small compound wall, which seems an embellishment rather than a necessity here. These are the only structures in sight within hundreds of miles of inhospitable snow-capped mountains and glaciers. The station can house eight researchers in two dorms, and has toilets, a kitchen, and a laboratory.

From Himansh, the six glaciers under observation are anywhere between 1.3 miles and 63 miles away, each with different glacier lengths (0.6 to 18 miles) and area (0.6 to 68 miles). In this terrain and altitude, it can take a day or sometimes even a week to reach them. There’s no network, road, or facilities beyond the research outpost. The scientists are on their own.

Porters, who work on a government contract, are a crucial part of managing the logistics. To set up Himansh, they carried supplies and equipment weighing hundreds of pounds from Batal. Twice, the journey proved so arduous that porters dropped the equipment midway and walked off the job. Sharma calls these two incidents the most arduous phase of his career.

“Porters are our lifeline,” says Meshram. “For expeditions to the glaciers, both scientists and porters carry the equipment and food.” In her two months there, porters became a source of strength and support. Visits to larger glaciers may require camping in inhospitable conditions, and the porters connect these remote camps with the main station.

“We work in a small time frame, from May to October. We return before the winter begins,” Meloth says.

“We have to be prepared for the worst,” Sharma says. “Field scientists go through a rigorous health check up, but in my experience that is not enough to work in the Himalayas. The fittest people have had to leave.” In extreme cases, lack of oxygen at high altitude can cause pulmonary edema. The nearest hospital is half a day away.

“Glaciologists have different challenges in different regions,” Meloth says. He was part of India’s first scientific expedition to the South Pole in 2010, and currently focuses on Antarctica. “I have been to all three poles and I can say the Himalayas is the toughest.”

Meloth’s experience in Antarctica and the Arctic before he visited Himalayan glaciers to set up Himansh was not as relevant as one might think. While it’s freezing in Antarctica, the continent’s comparatively smoother terrain allows scientists to use snow vehicles.

But the terrain of the Himalayas doesn’t support vehicles, and basic technology like drone imagery is useless. Since scientists had to carry their own equipment on expeditions, there was only room for a limited number of instruments. Add the harsh geography, lack of logistics, inclement weather, and occasional avalanche and you have quite the hostile work environment.

When they return from the field, the scientists and researchers live at the edge of the coastal city of Vasco-Da-Gama, Goa. The average work day at “Antarctica,” as the taxi drivers call the NCPOR main office, is vastly different from Himansh. Insulated in a quiet world of an Antarctic Ice Yard, freezing labs and air-conditioned offices a few miles from the tropical sandy beaches and partying crowds, the scientists continue their work.

At his office, Sharma is surrounded by the memorabilia from expeditions. He summarizes his two-decade-long experience of chasing glaciers: “There needs to be more research in the Himalayas.”

“By studying one basin or glacier, we cannot provide conclusive insights on the HKH region. We need collaboration,” he says. NCPOR’s multi-institutional, interdisciplinary program HiCOM (Himalayan Cryospheric Observations and Modelling), which began in 2017 to undertake long-term projects across the region, is still in its nascent stage. The rate of glacial retreat, however, is not as slow.

“It is not just the people who live immediately downstream who will be affected if the glaciers melt,” Meshram explains. “We may not live near the Himalayas, but all our lives will be impacted.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook