How to Quarantine in a Ghost Town

Cerro Gordo has been abandoned since 1957. Now one man is social distancing there by himself.

On March 18, 2020, Brent Underwood arrived in the California ghost town of Cerro Gordo after driving 22 hours from Austin, Texas. The plan was to stay a few days, maybe a week, pinch hitting while the town’s usual caretaker left to visit his wife.

Then came the snow, as if sent from above to enforce social-distancing guidelines.

Today, some six weeks later, Underwood is still in Cerro Gordo—quarantined, snowed-in, and all by his lonesome. Without running water, he’s getting by on melted snow; without fresh food, a dwindling supply of canned goods and frozen chicken tenders; and without company, visits from a local bobcat and, perhaps, the occasional ghost.

It’s not exactly what Underwood had in mind when he purchased the town, with a friend, in 2018 for $1.4 million. “I kind of have this thing for history and hospitality,” says Underwood, who also owns an Austin hostel converted from a 19th-century mansion. For someone in that business, Cerro Gordo presented the ultimate, if not the easiest, opportunity: 22 buildings waiting to be made habitable, stark mountainous panoramas, and a literal bloodstain bearing witness to the town’s violent past as a mining community. Underwood recalls his first drive into the ghost town, along the final seven miles of winding dirt road. “My jaw dropped the entire time,” he says, as each turn revealed a new rock formation. “I’ve never seen anything like this in my life,” he thought to himself. After some fixing up, it would make a dream vacation destination. But, as we know, quarantine is not vacation.

Founded in 1865 by Mexican prospector Pablo Flores, Cerro Gordo enjoyed a brief but fruitful run as a silver-mining powerhouse. Indeed, by the end of 1869, tons of silver bullion had been transported from Cerro Gordo to Los Angeles, about 200 miles south. “What Los Angeles is, is mainly due to” Cerro Gordo, wrote The Los Angeles News that same year. The mining town, the paper continued, is “the silver cord that binds our present existence. Should it be uncomfortably severed, we would inevitably collapse.”

By its peak in the mid-1870s, the once-tiny village’s population had ballooned to nearly 5,000. But the ore bodies gradually “pinched out,” says Roger Vargo, coauthor (with his wife Cecile) of a book about the town, and the price of silver began to fall in 1877. By the 1880s, Cerro Gordo was all but abandoned, home to about 30 or 40 people. The town underwent a short-lived revival in the early 20th century, as zinc became more valuable and new technology made it more efficient to mine, but Cerro Gordo never again hosted more than a few hundred residents. The town was deserted for good in 1957, when its then-owner passed away.

Since then, it’s been visited only by caretakers, subsequent owners, and curious explorers such as the Vargos. Underwood and his friend learned of it from a Los Angeles real estate listing, and acquired the town despite being outbid. Their vision for Cerro Gordo aligned best with that of the prior owner, they were told.

And to be sure, Underwood doesn’t seem even slightly aggrieved by his current predicament. “Every day that I’m up here, I fall more in love with it,” he says. “I just get more excited about it the more time I spend up here.” Roger Vargo, who’s been in touch with Underwood throughout the quarantine, went further: “He’s having the time of his life,” says the town historian.

As of last week, Underwood estimated that he had about a week’s worth of food left on hand—frozen burgers, pasta, rice, and canned goods, some of which expired in 2015. He hasn’t seen a fruit or vegetable, he says, since March. Most of the food had been stocked by the caretaker, Robert Desmarais, and some by Underwood himself, though he was also handed a “lifeline” from an unexpected corner. “In the old saloon,” he says, “I went in the back kitchen, and there’s this huge cupboard that I never looked in.” Also in that saloon, in the card room, is a “bullet hole in the wall and a bloodstain right underneath it,” evidence of what Underwood calls “a pretty well-established card game gone awry … ” (Visitors have reported their cameras jamming up, inexplicably, in the room.) One wonders who stocked that cupboard.

Still, Underwood doesn’t sound concerned about his food situation. Though he can’t drive to buy groceries on account of the snow, he says he can walk four dry miles to meet a friendly courier from Lone Pine, the nearest town (more than 20 miles away). He’s also “raiding the pantry of each cabin one by one,” sometimes stumbling upon the odd box of pasta. “I’m not terrified of the prospect of being here for another week, as far as rations go,” he says. “I’m trying to just enjoy the time.”

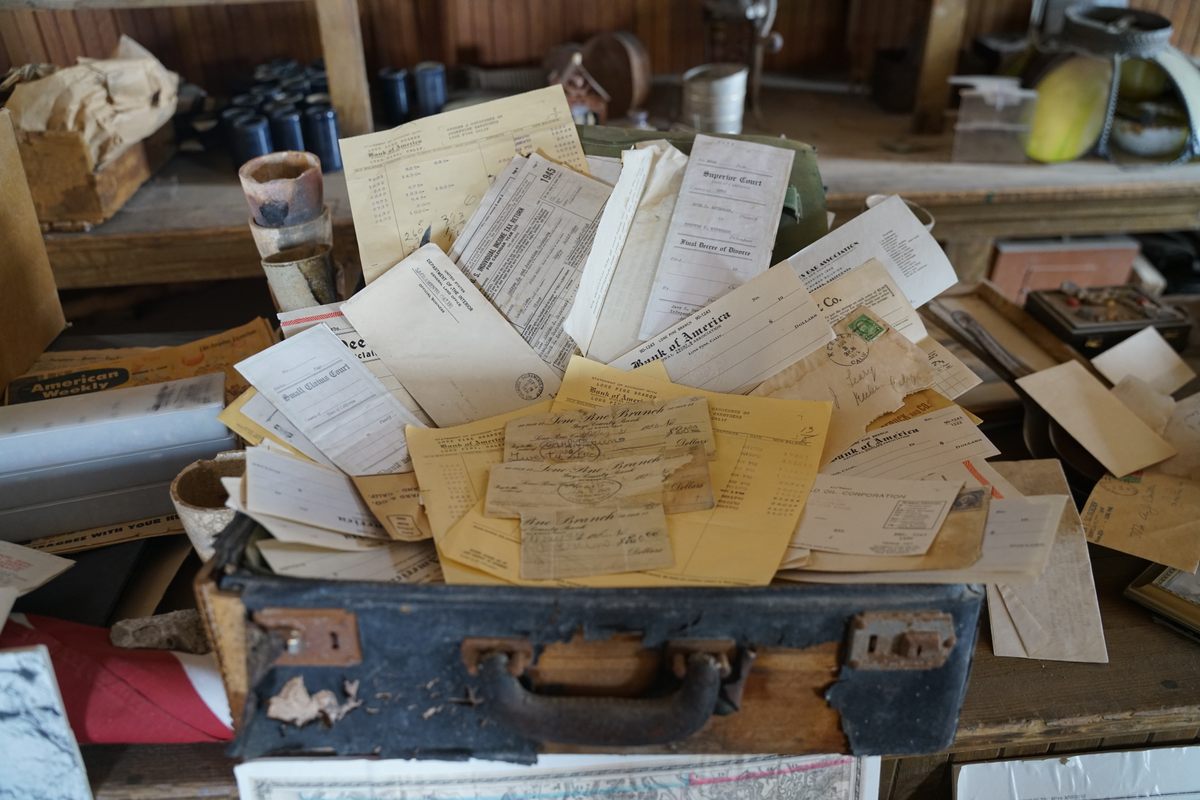

To that end, he’s been passing the days by continuing his day job remotely (as a marketing and hospitality entrepreneur), applying restorative touch-ups to these buildings he hopes to one day open to tourists, taking photographs of the starry night skies, and conferring with Reddit’s animal tracks community to identify the fresh prints he finds in the snow. (So far, a bobcat, a coyote, some mice—and a potential Yeti or bear.) He’s also stumbled upon some gems that bring the desolate town’s history vividly to life. In the town’s old general store, Underwood found a briefcase that makes up a miner’s partial biography, stuffed with bank statements from the 1910s, documents from lawsuits, divorce papers, and love letters, among other personal effects.

It’s the kind of find that can only burnish the town’s already notorious reputation for another commodity: ghosts. Though Underwood was a “skeptic” upon first hearing the stories, his position has since shifted to something closer to agnostic. His most arresting experience with potential paranormal activity came before the quarantine, during a visit several months ago. While watching the sunset from a cliff, Underwood saw movement in the town’s bunkhouse: curtains opening and closing, someone looking out the window. He wasn’t too concerned because he knew that contractors had recently been working on the property, but he then learned that they’d been gone for weeks. So the next day, Underwood—who has the only key—entered the bunkhouse, turned off all the lights, closed all the blinds, and padlocked it tight. When he returned to the cliff to watch the sunset, the lights were on once again.

Ultimately, however—with the exception of the bunkhouse, which he now tries to avoid—Underwood is as comfortable with the spirits as he is with his dwindling pantry: If the ghosts do exist, he just wants to “respect their space.” He’s sure they’ll return the favor.

And besides, what’s a ghost town without a few creaks and flickers? For Underwood, they don’t signal death so much as lives lived. “Even if there was another 300 acres in the mountains,” he says, Cerro Gordo couldn’t be replicated. The site wouldn’t “have the road that 5,000 different miners walked up and down.”

There’s also a clarifying, therapeutic effect to feeling that history all around you, he adds. “Every day, I walk by a grave that—there’s people in there that literally died from the Spanish influenza,” he says. “This town was impacted by that pandemic.” It brings to his mind the phrase memento mori, Latin for “Remember your death.” Being alone in Cerro Gordo, at this point in time, is “the ultimate memento mori,” he says. “It forces you to think about what’s important and what’s not.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook