The All-Female Culinary Clubs of 20th-Century France

Even Julia Child was a member.

With its chic restaurant scene and world-famous chefs, Paris attracts foodies of all stripes. Groups of female diners are an everyday sight, happy socializing as they enjoy exquisite dishes.

But that hasn’t always been the case. In fact, there was a time when women were barely accepted as restaurant-goers.

In the mid-19th century, France, defeated at Waterloo but still culturally dominant, invented modern haute cuisine. Eating out became a pastime rather than a necessity for the country’s bourgeoisie, an opportunity for conspicuous consumption and business talk. In keeping with the times, women were largely excluded. Few cooked or even waited on tables in the capital’s high-end restaurants, and even fewer visited them as customers without their husbands. Their unaccompanied presence would raise suspicions of prostitution.

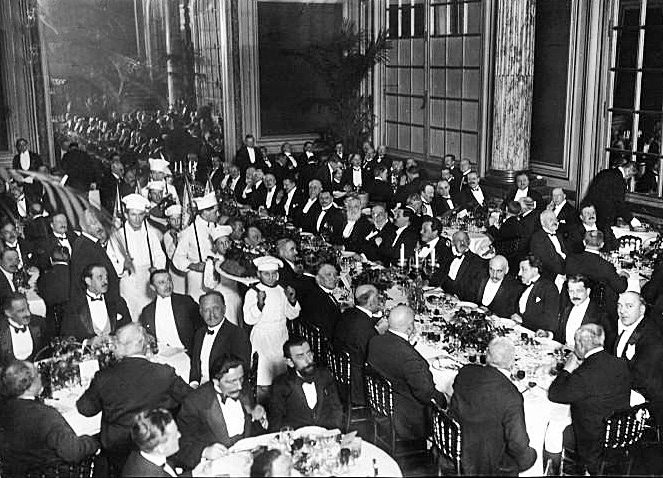

Then, a new institution appeared at the turn of the 20th century: gastronomic clubs. These loose brotherhoods of food lovers consisted of artists, politicians, and businessmen who knew their camembert from brie. They went by fancy names, such as “The Academy of Psychologists of Taste,” and organized unforgettable feasts that were often covered by the press. Club members enjoyed not only delicious meals, but also the privilege of tasting foods that were inaccessible to the lower classes, bumpkins from the provinces, and, of course, women. “It was thought that men wouldn’t be able to focus on their food if there were women around,” says Julia Csergo, an academic specializing in the history of French gastronomy. “With their sexual appeal and chatter, women would distract them. And their perfumes and make-up would allegedly distort the smell and taste of food.”

The most prestigious of these groups was Club des Cent, the Club of the One Hundred, a slightly secretive, invitation-only foodie society founded in 1912. Some of the most exquisite dishes of the time were served at its legendary banquets, such as the famous Belle Aurore Pillow, or L’oreiller de la Belle Aurore, pâté en croute with a lavish stuffing of up to 15 different types of meat, and Poularde Albufera, an elaborate chicken dish named after one of Napoleon’s generals. However, the club would not admit any women on the grounds that they were not able to appreciate fine food. The informal rule, according to Csergo, also reflected women’s meager presence in France’s public life: “From its outset, Club des Cent sought to attract powerful people from politics, media, and industry,” she says. “Practically no women held those positions at the time.”

But by the 1920s, France’s feminist movement counted hundreds of thousands of suffragettes, campaigning for women’s right to vote. When Club des Cent officially excluded women by unanimous vote in 1928, it was time for female foodies to strike back.

There are different accounts of how the first women’s gastronomy club was formed that year, but all point to one motivation—a response to the unbearable sexism of male clubs. According to one story, Maria Croci, an author and translator, came up with the idea at a gathering arranged by Rachilde, a literary figure of the time. “Men say that women don’t know anything about good cooking,” Croci protested, irritated by Club de Cent’s well-publicized exclusionary stance. Rachilde, an avowed feminist, encouraged her to respond in kind. Croci and Gabrielle Réval, another author, decided to found Le Club des Belles Perdrix, The Club of Beautiful Female Partridges, whose membership included playwrights, journalists, poets, and artists such as Aurore Sand, granddaughter of George Sand.

Another possibility is that the club was the female answer to Le Dejeuner de Grand Perdreau, a male-only gastronomic club whose gargantuan feasts attracted men of letters. Many of the original Belles Perdrix, including Croci’s husband, were married to members of that particular club.

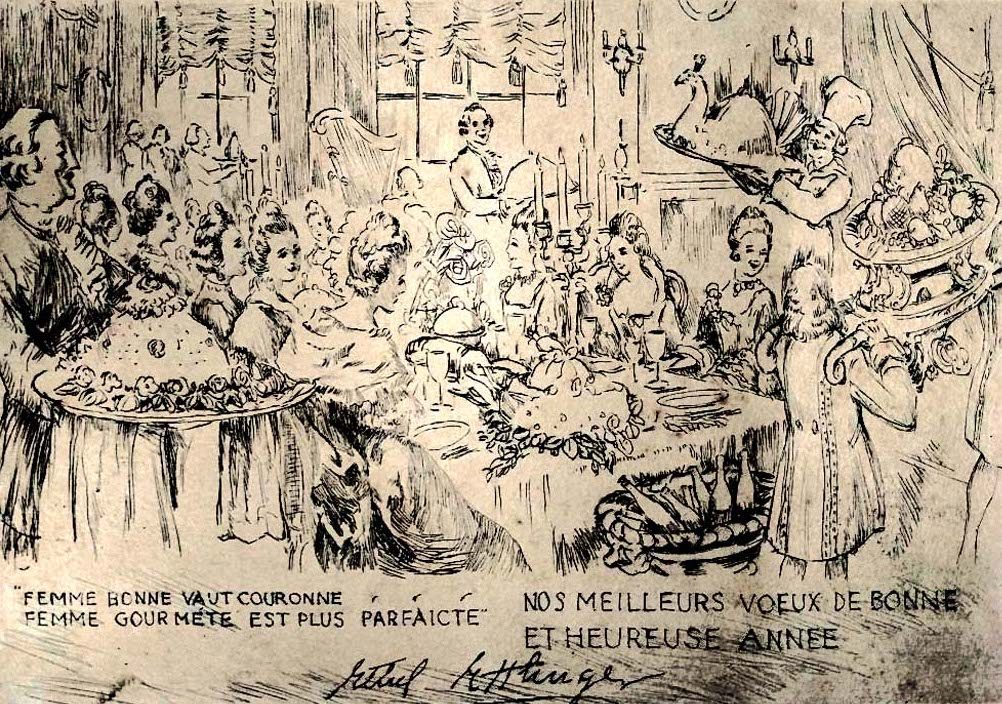

For several years, Les Belles Perdrix would meet at the finest Parisian restaurants to indulge in all things gastronomy, cook, and judge the skills of various professional chefs. On one occasion, Auguste Escoffier, the father of modern French cuisine, cooked for them a lavish meal that included veal sweetbread in slices à-la-favorite, foie gras parfait à-la-Sainte-Alliance, and roast partridge wrapped in vine leaves. Surprisingly, they did not totally exclude male gourmets. Each member was allowed to invite a male companion once a year, as long it was not her husband. In 1936, they founded one of France’s first culinary schools, the short-lived Académie des Cordons Bleus, aimed at promoting female chefs.

In 1930, Croci and Réval published “Les Recettes des Belles Perdrix,” part recipe book, part feminist manifesto. “They never claimed explicitly that their club was feminist, even if it included feminist figures. But its very existence was unsettling for a society that treated gastronomy as a male domain,” says Nelly Sanchez, an expert on the history of French women’s literature who edited a recent edition of the book. “They went to restaurants where women would only go accompanied by men. So they reclaimed fine dining as a female right.”

Associated with the hedonism of the interwar period, the Belles Perdrix would not survive World War II. Sanchez speculates that Croci’s fascist leanings, combined with the fact that many members of the club were Jewish, possibly led the club to be swept away by the upheaval that engulfed Europe.

Club des Cent’s men-only policy had one exception: members were allowed to bring their wives to its annual gala. Towards the end of that event in 1929, the club’s president took the opportunity to remind members why fine dining was a manly affair: “I salute the men at this table, without whose skill and knowledge, and whose capacity for [food] appreciation, this truly noble feast could never have happened,” he said.

That rubbed one attendee the wrong way. Ethel Ettlinger was a bubbly, confident American who had little time for chauvinists, and she stood to make a toast of her own. Her oratorical skills in French were good enough to push back against what sounded like gastronomic machismo, an anachronism in the era of suffragettes. Wasn’t it women who ran the kitchens and ordered meals? Hadn’t they trained the world’s most acclaimed cooks? She ended her short speech with an ambitious statement: “I have no doubt whatsoever that we could arrange a meal in every way as splendid and satisfying as the one we have just enjoyed.”

The enthusiastic applause she won from the other women was tacit approval of her suggestion. They decided to arrange a stupendous banquet to show their husbands that they were worth their salt, cheese, and wine. One offered her château to host the event. France’s famous Republican Guard officiated, with a horn quartet announcing the arrival of each course. Le Cercle des Gourmettes had just been born. Its name itself was a whimsical revolt against the rigidity of the French language; even today, the word “gourmette” signifies a type of bracelet, rather than a female foodie.

Les Gourmettes met every two weeks for a restaurant visit or a private lesson with a professional chef, followed by a lavish meal. Although they didn’t do much cooking themselves, the club’s rules required members to be ardent connoisseurs of the culinary arts; able to cook, order a perfect dinner, and arrange immaculate service and table settings.

By the early 1950s, the club was still going strong, with Ettlinger as its leader. Looking for American members, she asked a certain Julia Child, an expat taking cooking classes in Paris, to join. Although not strictly a feminist, Child enjoyed the cultural mélange and kinship with women who loved gastronomy. “It was terribly amusing, as I met all types of Frenchwomen and learned quite a bit about cooking,” Child would reminisce years later.

Through the group, she grew close to Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle, two French women who shared her passion for food. The three of them would arrive hours before the meal to assist the chefs and learn new skills. Together, they started a cooking school, initially called L’École des Gourmettes as a nod to the original Gourmettes. In 1961, they published Mastering the Art of French Cooking, a book that would introduce French cuisine to an American audience, while Child would become a household name with her TV show The French Chef. She once remarked that it was her experience as a Gourmette that marked “the real beginning of [her] French gastronomical life.”

Almost one century later, the legacy of the first women’s gastronomy clubs is indisputable. Today, the French capital’s high-end restaurants are full of groups of women, enjoying tasty dishes without having to worry about being mistaken for prostitutes.

However, a whiff of old-school sexism persists. Club des Cent, now a venerated institution of French gastronomy, still does not accept women as members. And if you scratch the surface of modern restaurant life, some things haven’t changed over the years. “If you go today to a restaurant during lunch break, you will notice fewer women than men sitting alone,” says Csergo. “For some, it’s still a taboo, so they bring their own meal and eat at the office or a public space.” Despite all the progress, the revolution started by the trailblazers of female fine dining remains unfinished.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook