The Woman Who Collected More Than 25,000 Menus

Her dream? To preserve the culinary history of the early 1900s.

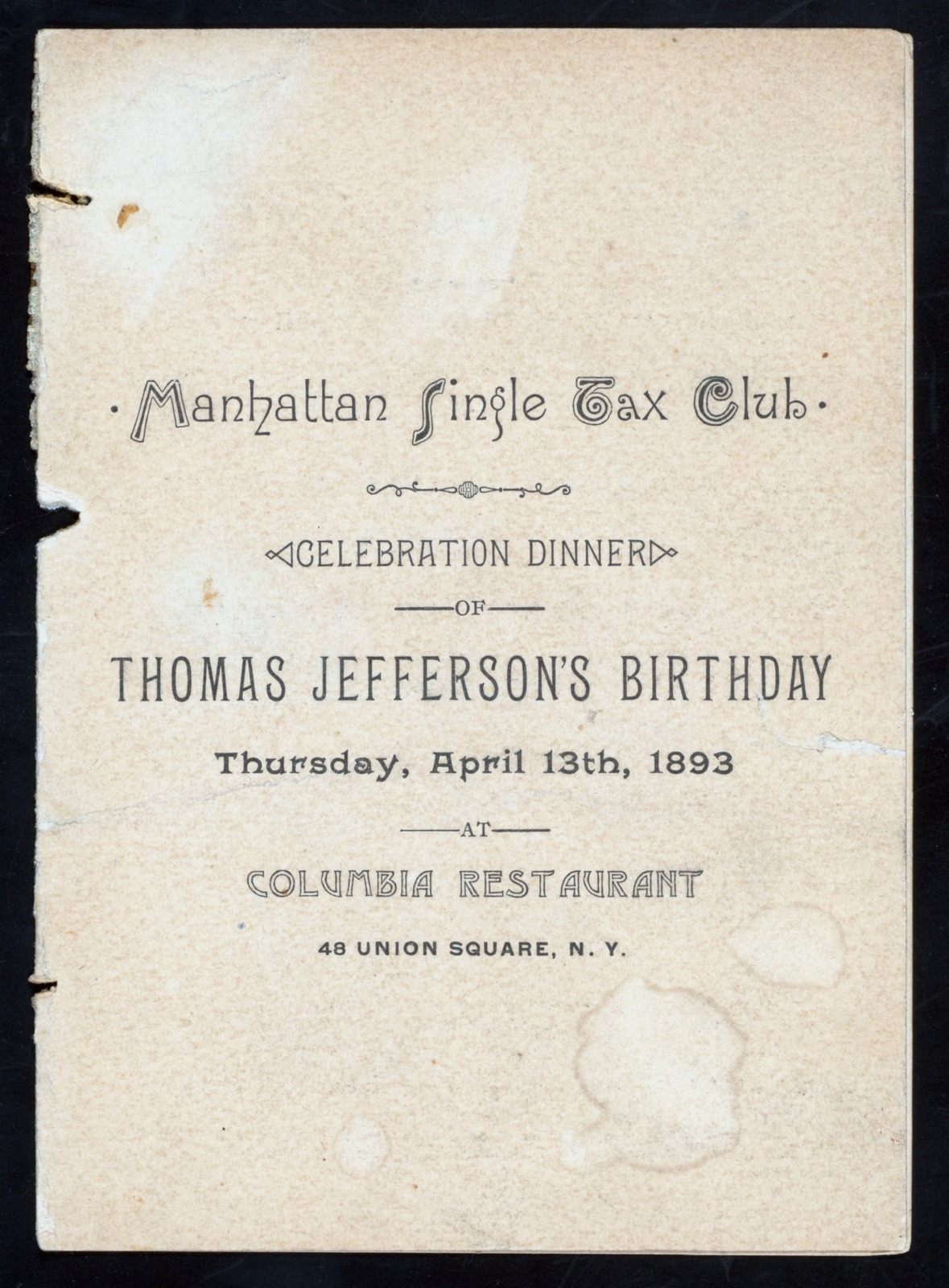

Frank E. Buttolph liked to say that she started collecting restaurant menus on January 1, 1900. At the Columbia Restaurant in New York, she said, she received a menu that was dated to the new century. Struck by the sight, she saved it. But that probably isn’t true, since her vast collection appears to have begun several years earlier. The New York Public Library, which now archives many of Buttolph’s menus, even states that she first contacted them about her collection a year prior, in 1899.

Frank E. Buttolph also didn’t always use that name. Born in Mansfield, Pennsylvania, in 1844, she was first known as Frances Editha Buttles. She changed her last name to “Buttolph” in 1900 after discovering that “Buttles” was a recent corruption of her ancestral name. Why she switched to “Frank” is less clear. What is clear is Buttolph’s great contribution to restaurant history.

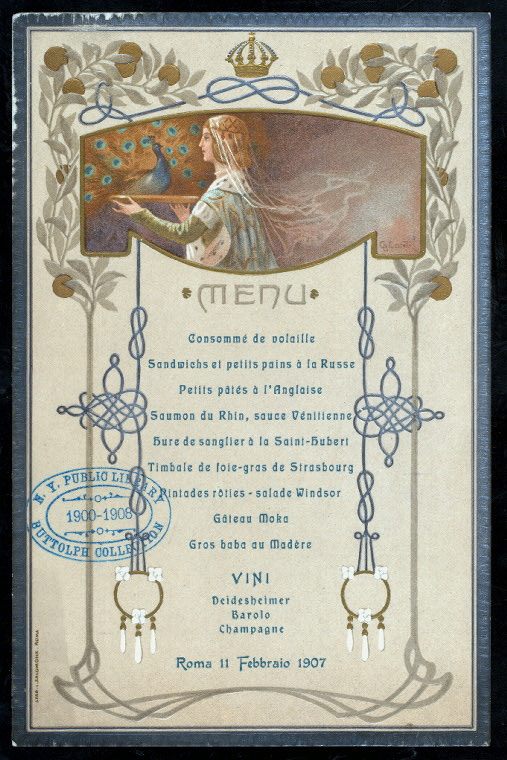

In 1887, after working as a teacher in New Jersey, Kentucky, and Delaware, Buttolph settled in Manhattan. She began swiping menus and, in 1900, the New York Public Library agreed to accept her collection. Her desire to amass as many menus as possible only grew from there. She began volunteering at the Astor Library, where she spent much of her time over the next 20 years. She sent out hundreds of letters to restaurants, transportation companies, chambers of commerce, government agencies, and newspaper editors to solicit donations. The letters went out to establishments across the United States and Europe. (Buttolph was fluent in multiple languages.)

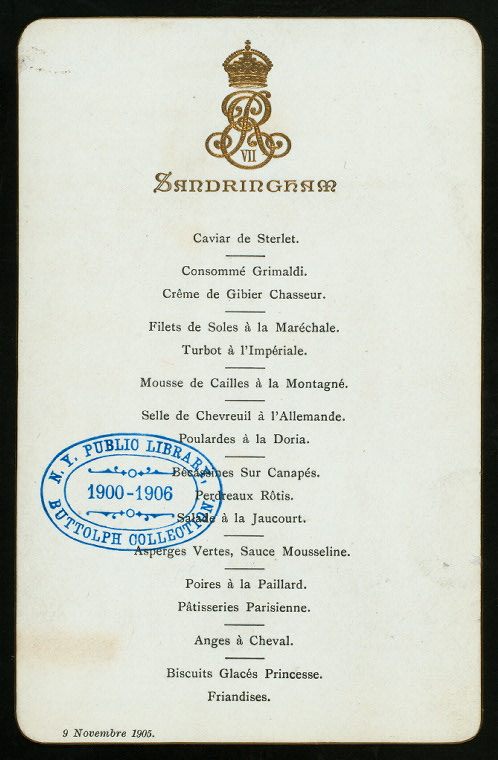

To attract ever more contributions, she took out ads in magazines such as Hotel Gazette, did numerous newspaper interviews, and enlisted aides to collect on her behalf—some of whom continued sending her menus for decades. According to Thirteen.org, she “frequently barged into private banquets at the city’s fanciest dining establishments and demanded a copy of their printed menu.” Once, in 1902, she sent the British Museum a copy of a menu card from a millenary dinner commemorating Alfred the Great, with the hope that the donation would encourage the museum to send her menus from the forthcoming coronation King Edward VII, though it doesn’t appear that they did.

Buttolph’s commitment to collecting menus came, she said, from her desire to preserve early 1900s culinary history for future scholars. Confirming this, The New York Times once wrote that “she does not care two pins for the food lists on her menus, but their historic interest means everything.”

She was a meticulous collector—not only in transcribing, dating, and organizing her menus with a detailed card catalog, but also about how they should be stored. When the director of the Astor Library tried to rubber-band menus together, she pushed back out of worry that it would leave marks.

In the press, this attention to detail often resulted in sexist caricatures. The New York Times called her an “unostentatious, literary-looking lady whose bugaboo is a possible spot upon one of her precious menus.” In a March 1905 article, The Literary Collector noted that the public initially regarded her as “a rather tiresome freak” who was wasting “a vast amount of energy … that might have been expended better.”

Buttolph was unfazed. By 1921, she had amassed more than 25,000 menus in several languages. She had menus from the debut of the Suez Canal, from royal courts, from birthday celebrations for famous historical figures such as Thomas Jefferson. Each menu bore her blue oval “Buttolph Collection” stamp, sometimes in multiple places.

In the early 1920s, she was dismissed from her volunteer position, reportedly because of her complaints about the whistling and untidy desks of her coworkers (and maybe because of accusations that she was stealing books). Her last written record before her death in 1924 is a letter to the Astor Library:

For many years my library work has been the only thing I had to live for. It was my heart, my soul, my life. Always before me was the vision of students of history who would say “thank you” to my name and memory.

Her dream of preserving a culinary record of the early 20th century has come true. Today, the Buttolph Collection of Menus at the New York Public Library offers more than 40,000 menus to scholars interested in food, restaurant, and cultural history. You can view many of the menus Buttolph collected here.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook