Found: A Seditious Cufflink From the Colonial Resistance Wardrobe

It holds a semi-secret message of opposition to the king.

In the years following the Stamp Act of 1765, in the American colonies, anti-British feeling was reaching a fever pitch. Around that time, the residents of Brunswick Town, North Carolina*, were drinking and smoking and, presumably, getting a little rowdy in their neighborhood tavern. Among them were radicals—colonists who refused to pay the stamp tax, and even forbade their governor from ponying up when he offered to do so for everyone. The entire town had become a hotbed of anti-crown sentiment.

How and when it happened is a mystery, but that tavern went up in flames within a few years, locking surviving bottles, pipes, a wasp’s nest, and colonial memorabilia in time. Now, a new discovery among those remains, a 250-year-old cufflink, shows just how openly those colonists were defying the monarchy. They were—literally—wearing their feelings on their sleeves.

The single cufflink was found by Adam Pohlman, an undergraduate at the East Carolina University, who has been volunteering on the archaeological dig of the Brunswick Town tavern site until it’s time to get back in the classroom.

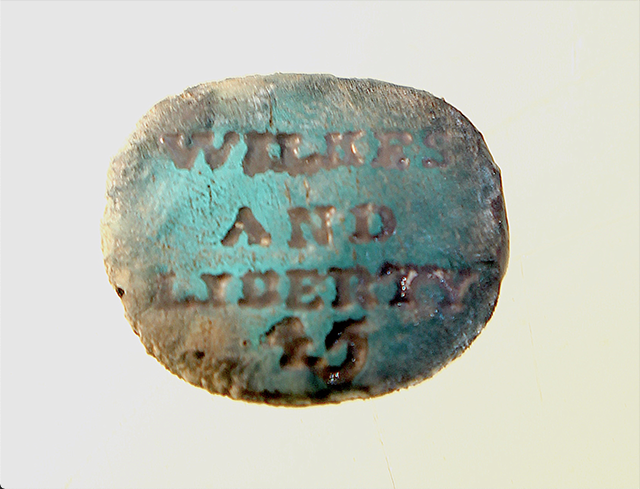

“It looked like a dirty piece of gravel. But we cleaned it up and could shine light through it,” says Charles Ewen, director of the Phelps Archaeological Laboratory and leader of the dig. “It was a translucent blue glass, a bead-type thing, a little over a centimeter in length.”

But it was a little more than a bead-type thing. On it was cut: “WILKES AND LIBERTY 45.”

“Huh, I wonder what that is,” Ewen remembers saying. “I looked it up and dang! This is exactly what Brunswick Town was about.”

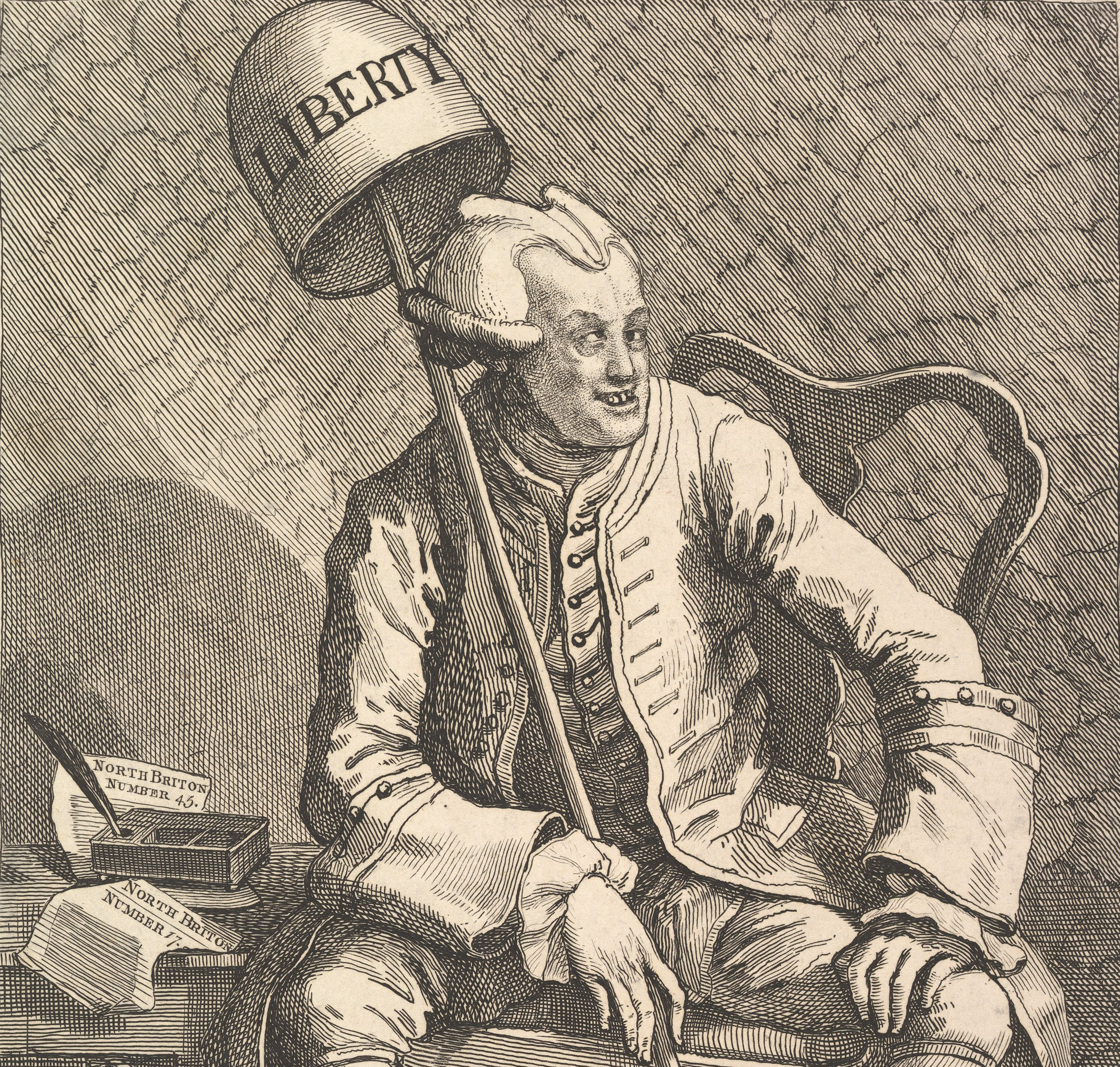

In the run-up to the American Revolution, a British politician named John Wilkes was constantly running his mouth. When the Earl of Sandwich told the notorious rabble-rouser, “You will die either on the gallows, or of the pox,” Wilkes retorted, according to the writings of Rutgers University scholar Jack Lynch, “That must depend on whether I embrace your lordship’s principles or your mistress.”

Salacious remarks aside, Wilkes was an outspoken opponent of the king, which made him quite popular in the colonies. In April 1763, he published the latest edition of his inflammatory rag, The North Briton—issue number 45—in which he openly criticized a decision of King George III. This was sedition, and Wilkes was forced to flee to Paris, where he lived for the next four years, before being imprisoned upon his return to England. Shouts of “Wilkes and Liberty!” resounded in the streets of London, from a populace demanding the vocal politician be cleared of the charge.

In Charleston, South Carolina, a Club Forty-Five, referencing Wilkes’s notorious publication, was set up in his honor. Members met at 7:45, drank 45 toasts (!), and concluded meetings at 12:45. It was chummy, cult-like, and club-like fanaticism in support of a man who dared to openly criticize the king. Perhaps, Ewen says, the cufflink belonged to a club member. After all, the founders of Brunswick Town hailed from just north of Charleston.

“Maybe it was worn by like-minded people, [who] could show ‘Wilkes and Liberty 45.’ Being in Brunswick Town, you weren’t going to be harassed” for that sort of political statement, says Ewen. “It’s a semi-secret sign. And what better place to find it than in a tavern, where you know this talk is going to happen!”

Ewen was not certain of the find’s purpose at first. But then he found Jason Sandy, a London-based mudlark who had documented a similar find—3,920 miles and an ocean away, in the muck of the River Thames. Two years ago, Sandy uncovered a similar stone there, no wider than a fingertip. It wasn’t an exact match—the stone was darker and in a pewter setting—but the sentiment was identical.

“Because it has been rolling around in the river for hundreds of years, the surface of the glass is cloudy,” Sandy says via email. “So the letters behind the glass are difficult to read.”

But close examination revealed: “WILKES AND LIBERTY 45.”

Whether these cufflinks were connected by maker or group is not known, but they clearly show that the message they carried spanned the pond, from a dissident town in the American South to right under the nose of the king himself.

*Correction: This story was updated to clarify that the Brunswick Town historic site is in North Carolina.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook