The Oddly Named Energy Bar That Rocketed to the Moon

Pillsbury designed Space Food Sticks for astronauts before launching them in grocery stores.

Before the energy bar took over the snack aisle, before it appeared in gym bags and in the hands of marathoners, and before it became a $5 billion global market, the energy bar went to space.

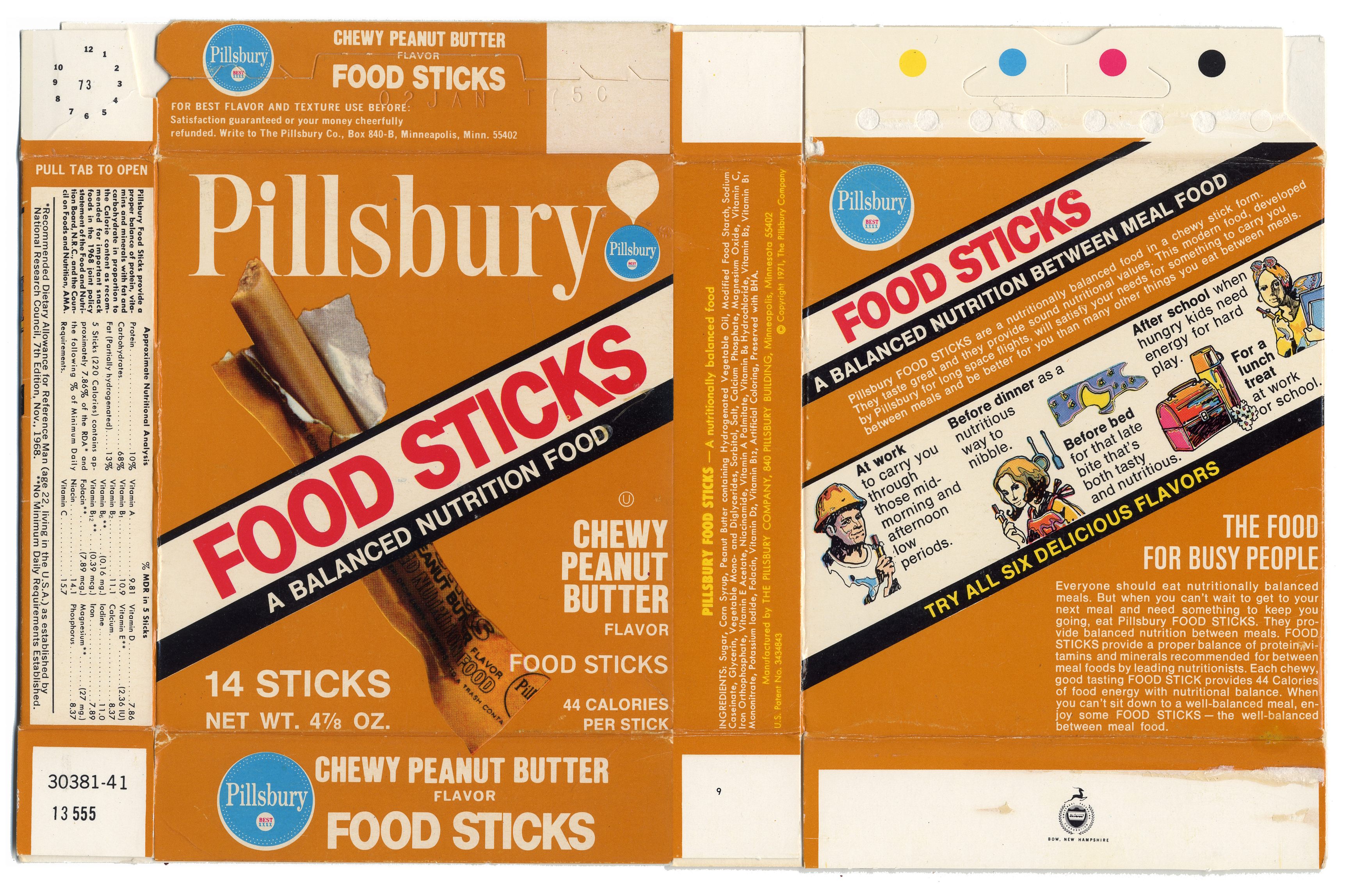

In 1959, the Quartermaster Food and Container Institute of the United States Armed Forces asked Pillsbury to develop food for astronauts. Thus commenced a series of collaborations that would feed men on the moon and launch pioneering developments in American food technology. In partnership with U.S. aerospace and military programs, Pillsbury created a variety of cubed and “compressed foods.” One of these was a tubular contingency food meant to sustain astronauts should they remain confined within their pressure suits in an emergency. This rod-shaped food, designed to be attached to the suits and consumed through a port in the helmet, would, in 1969, become known as Space Food Sticks, when Pillsbury placed them in grocery aisles as the first mass-produced, commercially released energy bars.

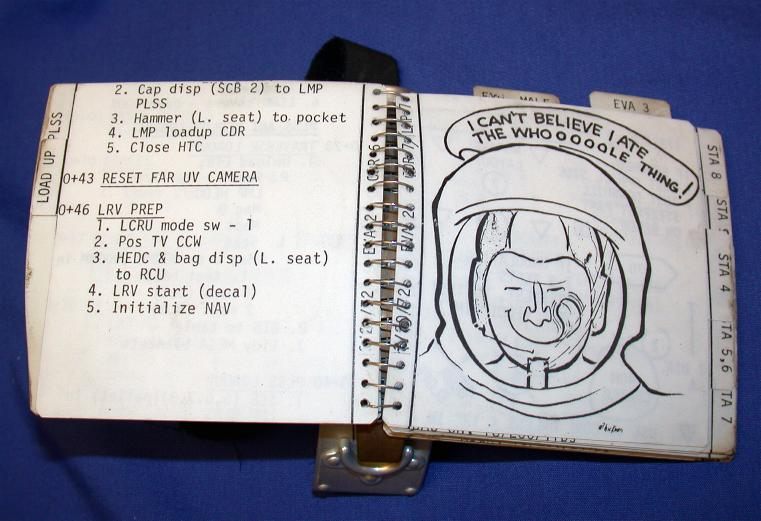

Protein bars such as Tiger’s Milk were already being sold in specialty health food stores, but Space Food Sticks took the concept to new heights. A modified version of the Sticks, each eight inches long, went to the moon on Apollo 11, Apollo 12, and Apollo 15, velcroed onto the astronauts’ helmets for easy reach and enjoyment. In different records of the Apollo 15 mission, they were variously referred to as food sticks, fruit bars, Caramel Sticks, and Nutrient-Defined Food Sticks. In 1973, another modified version of the Sticks appeared on the menu on Skylab 3, the second manned mission to the first American space station, Skylab. For two months, the flight crew chewed on the bars every third day, in a meticulously designed meal plan.

Their association with idolized astronauts helped make Space Food Sticks a popular American snack. (Tang experienced a similar sales bump after John Glenn drank it in orbit.) Pillsbury marketed them as a nutritionally balanced food, and earthlings seemed to appreciate the convenience as much as astronauts. But most of all, that the bars were attached to astronauts’ suits made them cosmic culinary wonders to legions of young, aspiring astronauts. It helped that they tasted a bit like Tootsie Rolls and came in a variety of candy flavors, such as chocolate, caramel, and peanut butter.

That popularity waned as NASA moved beyond Space Food Sticks, and Pillsbury, in a dubious marketing move, dropped “Space” from the name. (Imagine having to sell a product named “Food Sticks.”) They were discontinued in the 1980s, although they lived on as a cult favorite in Australia, sold by Nestlé until 2014, and named by Australian Olympic swimmer Ian Thorpe as one of his favorite snacks.

But Space Food Sticks left a legacy that goes beyond snacks. To ensure the Sticks were safe space food, the scientists at Pillsbury, NASA, and the U.S. Army Laboratories, led by Pillsbury microbiologist Howard Bauman, developed pioneering hazard-analysis measures. This led to the creation of the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) system of quality control, which Pillsbury adopted company-wide. Eventually, they helped train Food and Drug Administration inspectors. That the FDA now requires preemptive analysis of how food could get contaminated, rather than only looking at final products, owes a debt to space food sticks and NASA’s need for certainty that their astronauts’ meals would be uncontaminated.

These tubular treats might have remained relegated to space lore had it not been for Eric Lefcowitz, preservationist of pop culture from the golden years of space travel and an author of books on The Monkees.

In 1999, Lefcowitz, 58, who lives in Port Washington, New York, was working on a series of articles called “Countdown to the Millennium,” which revisited futuristic ideas such as flying cars and household robots. His piece on Space Food Sticks generated so much commentary that he set up a website called the Space Food Sticks Preservation Society in homage. Thousands of people submitted memories. “The day they took Space Food Sticks off the market was the day my childhood was over,” wrote one reader. They tasted “a little bit like chocolate laced with rubber bands,” recalled another.

Lefcowitz sensed a market for relaunch. He imported a few boxes from Australia to test and, with the help of a food scientist and a candymaker, re-engineered the snack and released chocolate and peanut butter versions in 2006. “A truck would drop off 6,000 pounds of Space Food Sticks,” says Lefcowitz. “I would think, ‘Oh my goodness, how am I going to sell these?’ And eventually they would be sold.” For eight years, Lefcowitz sold his Space Food Sticks in candy stores and gift shops at the Kennedy Space Center, Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, Disney World, and the American Museum of Natural History, among others. But then the candy manufacturer, Richardson Brands, was bought out and his contract with them fell through.

In 2016, Vice interviewed Lefcowitz about the bars. There were no Food Sticks in production, but, Lefcowitz says, “I just improvised on the spot that I was going to make Space Food Sticks into a cannabis edible.” The Vice journalist took the idea seriously, which, unexpectedly, began to turn his joke into reality. Immediately Lefcowitz heard from interested representatives in the cannabis industry.

Since then, the author and retro candy entrepreneur says he has toured cannabis facilities in Colorado and California, and created a cannabinoid model of the Sticks. In partnership with a cannabis-edibles-focused magazine, he hopes to launch cannabinoid-infused Space Food Sticks for the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing in July.

From the astronaut dreams of ‘70s children, hiding in their blanket space stations, drinking Tang, and snacking on Space Food Sticks, to the quirky motivations of an irreverent Willy Wonka, these retro snacks have come a long way.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook