Exploring America’s Largest Collection of Early Tavern Signs

Early tavern signs at the Connecticut Historical Society. (All photos: Luke Spencer)

The early American colonists were ferocious drinkers. It’s thought that the average person back then inhaled around six gallons of booze a year, compared today’s average of two. Hot ale flips, warming wassails and planter’s punches were consumed in such alarming quantities that Benjamin Franklin published over 200 synonyms for being tipsy in the Pennsylvania Gazette on January 6th, 1737. “Gather’d wholly from the modern Tavern-Conversation of Tiplers,” he wrote, “I do not doubt but that there are many more in use.”

Such was the standing of the tavern in the fledgling society, that colonial law actually required every town to have one. In low-ceilinged rooms, the early colonials would gather and, in the words of Benjamin Franklin, start the evening “loose in the hilts,” gradually becoming “nimptopsical,” finishing the night “wamble Crop’d,” before stumbling home “right before the Wind with all his Studding Sails out.”

The signage, though, was a rather difficult design challenge. While today restaurants and bars are often easily identifiable by the form and shape of their buildings, historic watering holes were virtually indistinguishable from the private residences on either side of them: They were literally public houses. The painted and carved saloon signs hanging outside would signpost to visitors that food, drinks and lodging were to be had inside.

Being made of wood, many of the old tavern signs have been lost to time. Between 1750 and 1850, there were approximately 50,000 of these signs mounted up and down the Eastern seaboard. Only a fraction of them still exist. The largest collection of colonial-era bar and inn signage in the country, at the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford, counts 60 specimens.

In addition to demanding each town should have a tavern, colonial law also stipulated that a sign should be hanging outside of it. In Connecticut, the law stated “some suitable Signe set up in the view of all Passengers for the direction of Strangers where to go, where they may have entertainment.” Over in Massachusetts, every tavern, “shall have some inoffensive sign, obvious, for the direction of strangers posted within three months of its licensing.”

While their English counterparts enjoyed fanciful names, such as Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese (Fleet Street, London, opened 1538), or the Hung, Drawn & Quartered (situated near London’s site of execution, Tower Hill),or were named in honor of a monarch or local nobleman, American alehouse signs were much simpler in style. The earliest signs favored bold visuals with little text, indicative of a period when not everyone could read. Trees and horses were popular motifs. For coastal towns, ships, anchors and whales were common.

The earliest example, from 1748, was painted on a plain piece of wood advertising “Entertainment for Man and Hors.” The next stage of tavern signs incorporated the name of the proprietor offered hospitality inside, such “Entertainment by R.Angell - 1808.” This addition of the innkeeper’s name actually led to the current scarcity of early signs: When the taverns changed hands, the old sign was either painted over or replaced.

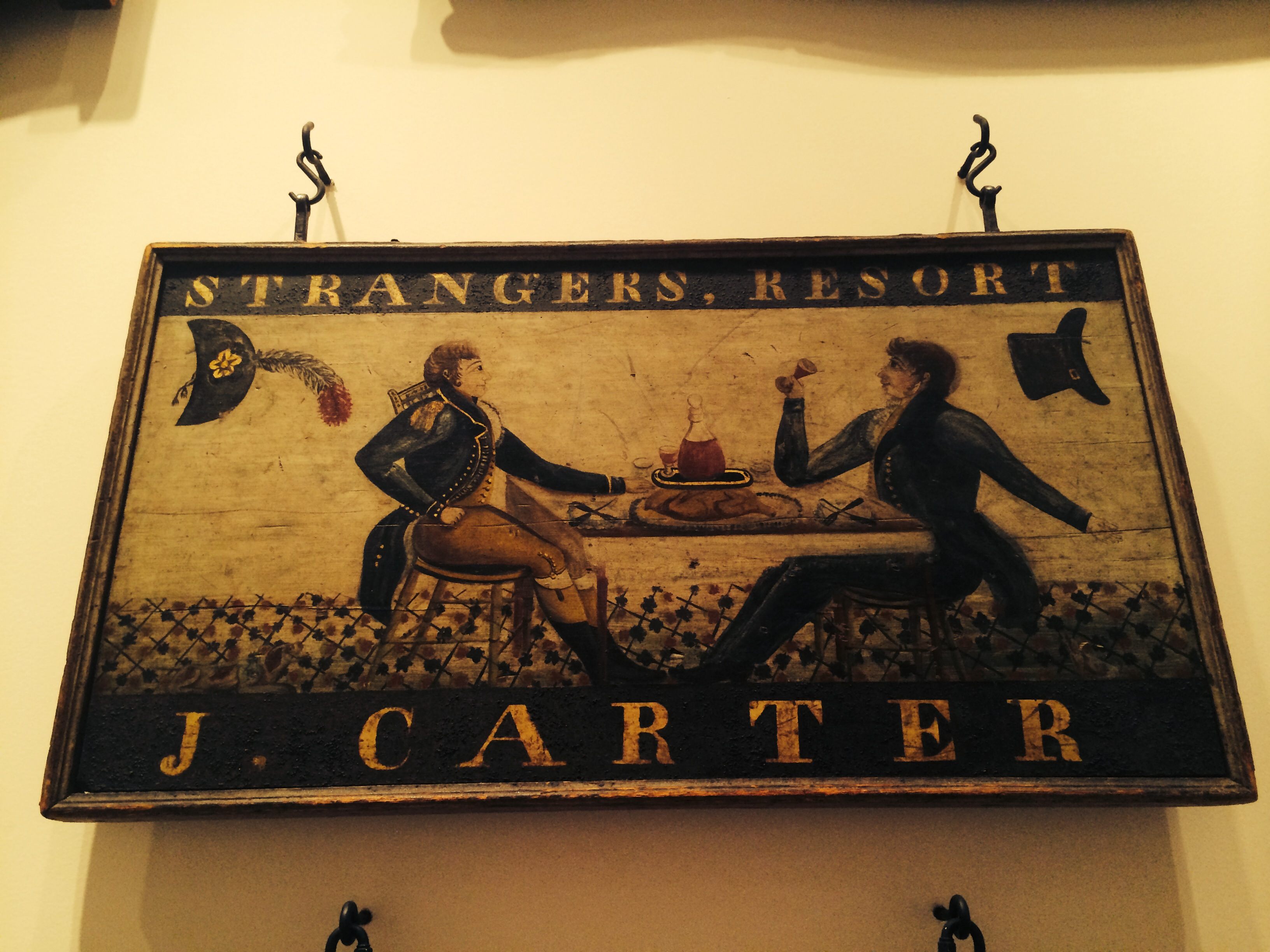

As travel within the newly consolidated United States increased in the early 19th century, the local drinking dens morphed into places to stay, too. Inns such as the one Jared Carpenter opened in Killingworth, Connecticut in 1823 were advertised as “Stranger’s Resorts,” with a sign showing a military officer sharing his table with a well-dressed businessman, a carafe of red wine, and a roasted chicken.

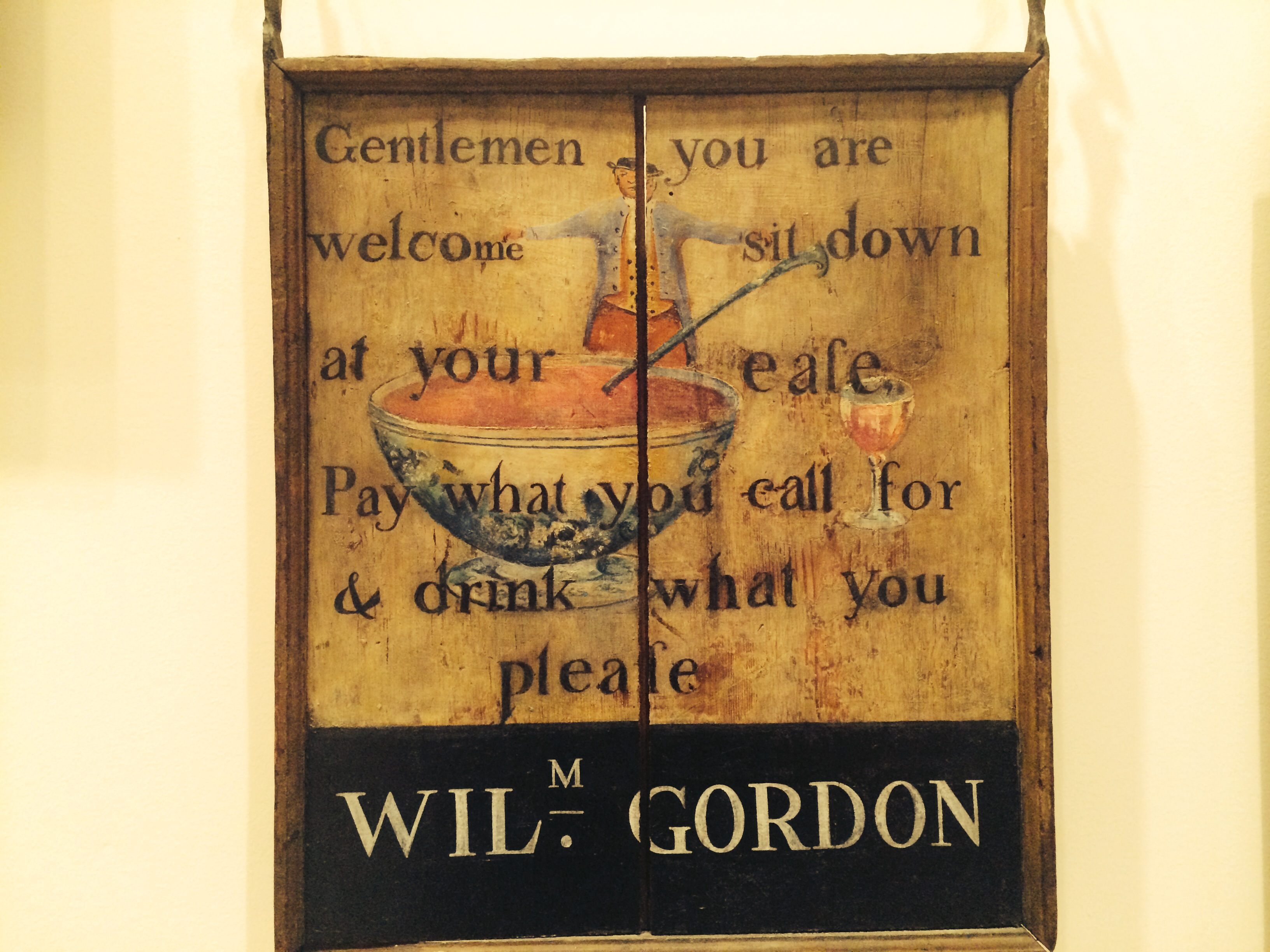

While the majority of tavern signs have been lost to time, the Connecticut Historical Society’s remarkable collection evokes the earliest days of America’s boozing habit, where establishments such as William Gordon’s in New London, Connecticut generously invited “gentlemen” to “sit down at your ease”—“Pay what you call for & drink what you please.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook