Endurance Starvation Was Once a Crowd-Pleasing Sport

While Greece and England were trying to revive the Olympics, the rest of the Western world was obsessed with hunger artists.

David Blaine suspended in a box by the Thames, London, in 2003. (Photo: james.spector/CC BY 2.0)

On September 5, 2003, magician David Blaine stepped into a clear acrylic box and was hoisted into position above the Thames River. There he would dangle for 44 days, in full view of passersby. He would eat nothing. He would drink only water. In the course of his ordeal, he was taunted by onlookers who hurled rotten eggs and hamburger patties at his transparent prison.

Others blew horns and beat drums to keep him awake at all hours; a radio DJ named Bam Bam exhorted listeners to shout his show’s “ring-a-ding” jingle from Tower Bridge nonstop for 24 hours. Specialists looked for the hoax: surely, Blaine’s water was supplemented with glucose or thiamin and other nutrients. Maybe he had a double. Maybe he was a hologram. Even after Blaine emerged from the box, thin and shaking, doubts remained.

Hunger artists were once a type of sideshow performer as well-known as sword swallowers, horse divers, and snake charmers. By the late 1800s, they were prevalent enough to inspire category splitting along the lines of mods-versus-rockers. Hunger artists weren’t human skeletons—people who ate but looked like they didn’t. Nor were they “fasting girls”— young women who claimed not to need food thanks to prayer or fairies—or ascetics seeking spiritual enlightenment through deprivation. Instead, they were men (almost exclusively) who went without food for weeks at a time to prove it could be done.

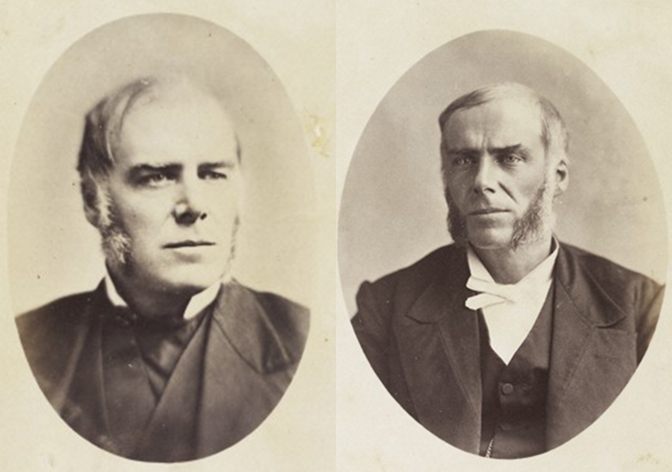

Henry S Tanner, before (left) and after (right) his 40 day fast in 1880. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/cropped/CC BY 4.0)

Public fasting was very much an endurance sport that demonstrated physical prowess, kind of the inverse of weight lifting. That’s part of why it was thought of as a manly thing to do. It had a lot of similarities with extreme long distance running; the marathon is, after all, based on a legend in which Pheidippides collapses to the ground and dies immediately after running such a long distance.

The hunger artists’ heyday coincided with the Victorian fad for mountaineering and a half dozen attempts to launch the modern Olympics; all three blossomed during an extended European and North American peacetime when newspapers were eager to fill their pages with new feats of strength and persistence, piped in through newfangled telegraph machines.

When Henry Tanner performed a 40-day fast in New York in 1880, under the supervision of the U.S. Medical College, spectators were admitted for 25 cents a ticket, the 2016 equivalent of about $6. They came in throngs, spurred by breathless newspaper coverage, to watch Tanner in his rocking chair, mopping his face with damp cloths that were sometimes inspected to ensure they didn’t secretly contain soup. Those who couldn’t attend sent 300 to 500 pieces of fan mail a day.

On the final day of the fast, admission was raised to 50 cents a ticket, for a box office take estimated at $2,000 ($44,000 in today’s dollars); Tanner also received a $1,000 reward from William Hammond, a former U.S. Surgeon General convinced that surviving more than 30 days without food was impossible. After his 40-day fast, Tanner went on to open a successful health clinic in southern California, where he mentored other fasters pursuing both medical and performative excellence.

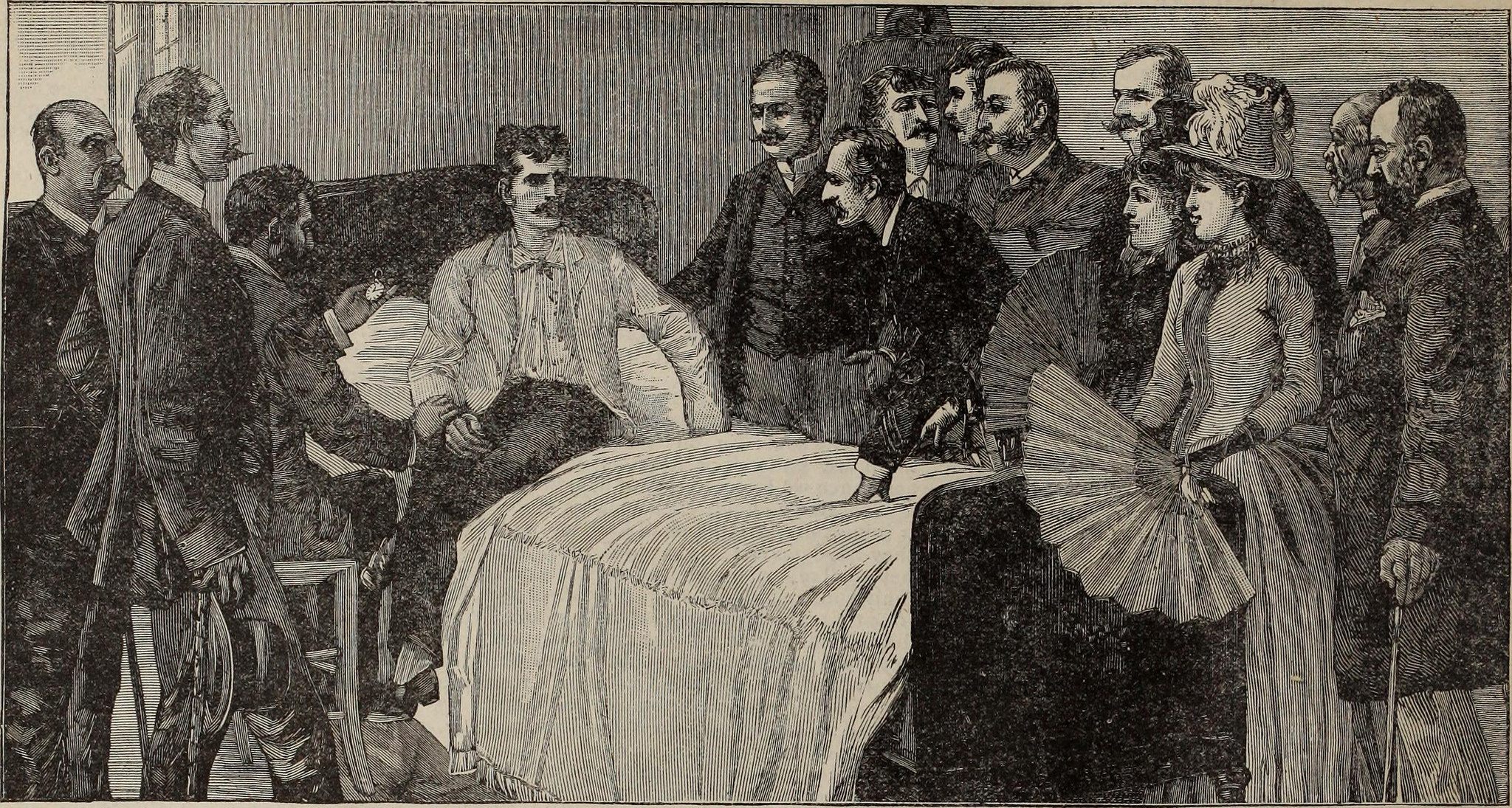

Giovanni Succi being examined by physicians after his 30 day fast. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

Tanner wasn’t even the highest achiever in the field. That honor belonged to Italian superstar Giovanni Succi, probably the most direct inspiration for Franz Kafka’s short story “A Hunger Artist,” which many modern readers presume to be an allegory along the same lines as the cockroach in The Metamorphosis. But Succi was perhaps even stranger than his fictional counterpart: His fasting career began at the age of 32, and included more than 30 public fasts in the space of 20 years—five of them in 1888 alone.

Although today Succi is better remembered for his collaborations with physiologist Luigi Luciani, which established a lot of what we know about the physiology of starvation and its effects on the central nervous system, his contemporaries viewed him as more of a wildly eccentric pop star. Succi’s most rational explanation for his obsession with fasting was that he’d suffered from liver disease which had made him temporarily unable to eat, and had been fascinated to discover how long he could go without food. However, he also sometimes claimed to have the spirit of a reincarnated lion and access to magical potions. He was committed to two mental institutions, but given the public appetite for starvation art, it was hard to claim there was anything wrong with him. He was released without diagnosis.

He drew crowds across Europe and America, who he regaled with stories of his days as a commercial trader and traveler in Africa—a way to pass the time during increasingly lengthy fasts: first 30 days, then 50, then 66 days long. To further demonstrate his vivacity, he added horseback rides, gymnastic exercises, and fencing bouts mid-fast. In 1907, when the first cinema in Bologna opened its doors, Succi was there in the lobby, fasting in a glass cage, his entertainment value a surer thing than newfangled moving pictures.

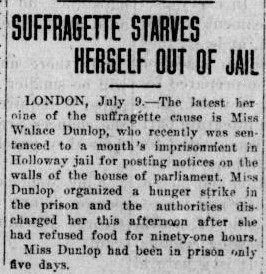

A newspaper article about British suffragette Marion Wallace Dunlop who went on hunger strike in prison. (Photo: Arizona State Library/Public Domain)

Public interest in hunger artists tapered off once the 20th century got underway. As with any multi-decade fad, it’s hard to point to a single terminating factor, but it’s probably not a coincidence that in 1909, imprisoned British suffragette Marion Wallace Dunlop went on hunger strike. This tool of political protest was quickly adopted by other suffragettes in both Britain and the United States, to the outrage of both governments, and spread to Irish Republicans.

In the face of these widely-reported battles against political repression and force-feeding, not to mention anti-imperialist protest fasts by Mohandas Gandhi and other Indian revolutionaries throughout the 1920s and ‘30s, it was hard to view aimless displays of extended starvation as light amusements. (Indeed, when David Blaine embarked on his 2003 stunt, he was criticized for his insensitivity to the families of Irish hunger strikers.)

By the 1920s, the remaining hunger artists were less like sideshow performers and more of a footnote to a record-setting mania that included flagpole sitters and dance marathons. In 1926, a German who billed himself as “Herr Jolly” made $35,000 from 300,000 observers as he completed a “record-breaking” 44-day fast in a traditional glass cage, but successors like Signor Venteg and the fasting double act Fastello and Harry barely broke even. A new Succi-surprassing record was eventually set by another German, “Heros the Hungerer” (real name: Willy Schmitz), an ordinary looking middle-aged man in a skinny tie and button-down shirt, who spent 78 days without food in 1953.

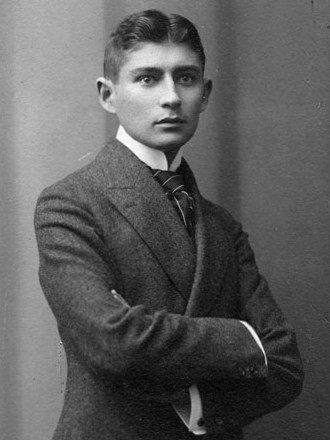

Franz Kafka, author of The Hunger Artist. (Photo: Bodleian Library/Public Domain)

Although Guinness refuses to track the world record for performative fasting, there’s been a small competitive resurgence since 2003, as Chinese and Russian challengers have surpassed David Blaine’s 44-day starvation stunt “record,” seemingly unaware of the higher 78-day bar set by Schmitz. As Kafka says of the diminishing commercial success of his fictional hungerkünstler, “we live in a different world now.” But if it’s harder now to accrue wealth and fame as a starvation professional, it’s not because the public lost interest; it’s because there’s too much competition.

Today, we can watch the modern variation of stunt fasting through the glass boxes in our living rooms, thanks to shows like The Biggest Loser and Celebrity Fit Club. While we engage in a centuries-old debate over whether it’s healthy, whether it’s fake, and how high the numbers on our personal fitness-tracker wristbands might go, perhaps we can take inspiration from another Kafka quote, from “Investigations of a Dog”: “So long as you have food in your mouth, you have solved all questions for the time being.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook