Disney’s Unlikely Garbage Innovation Was Supposed to Sweep the Country

It turns out, though, that utopia kind of sucks: the trash tubes ended up only getting as far as tiny Roosevelt Island.

There is an island off the coast of Manhattan that is directly connected to Walt Disney World via a series of tubes. (Nope, not that series of tubes.)

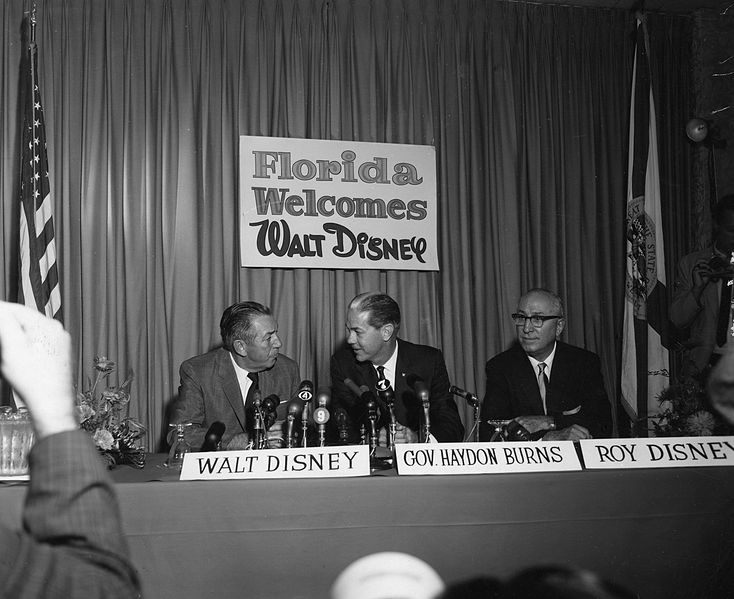

On April 30th, 1969 the Walt Disney Company convened a festive press conference at a hotel in Florida to unveil the details of their grand new project, Walt Disney World. The sprawling 25, 000 acre paean to the future, 16 miles outside of Orlando, was slated to open in 1971. Here, they announced, would be 450 acres of waterways and beaches, monorail and aquatic transportation, five theme-hotels with thousands of rooms, rides, restaurants and other mind-boggling novelties.

An ensuing press release underlined such innovations, but alongside the magical fare was a much less glamorous item: “Aerojet-General Corporation, a subsidiary of the General Tire & Rubber Co., is designing an automated trash collection and removal system for use throughout Walt Disney World.”

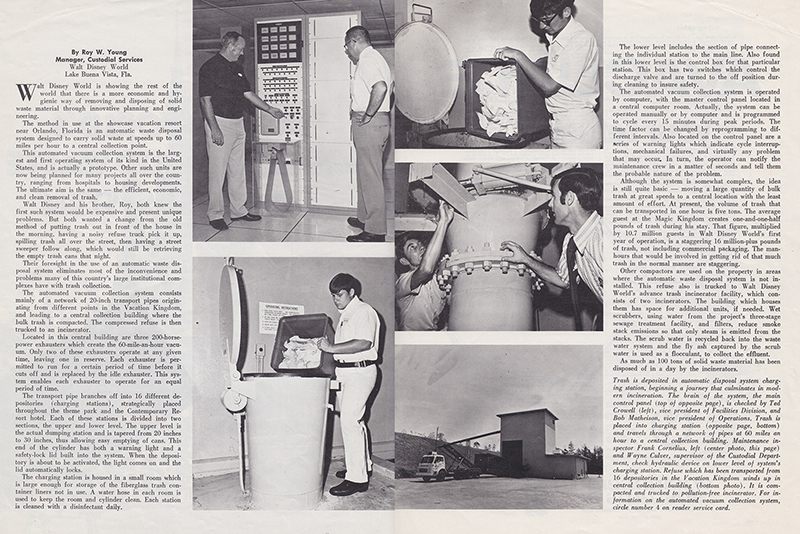

An article on Disney’s waste disposal system, from the 1973 issue of Executive Housekeeper. (Photo: Courtesy IEHA)

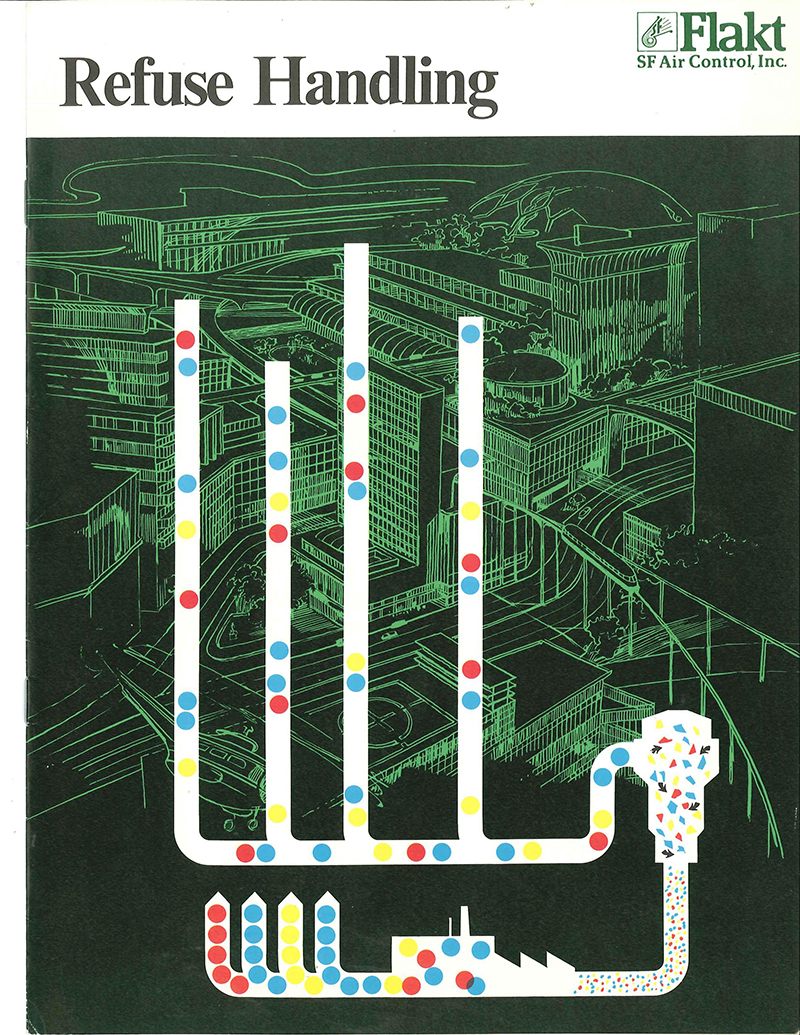

The system that the company planned to install in the new kingdom was an Automated Vacuum Collection system, popularly known as AVAC. Invented in Sweden in the early 1960s, the system involved depositing trash into a series of underground pneumatic tubes that would then rocket the garbage to a central sorting area. At the time, this represented the cutting edge of trash collection technology. In 1971, Walt Disney World would be the first place in the United States to boast such a system. But, declared the optimistic press release, the system “holds great promise for communities of the future because of its efficiency and cleanliness.” But although municipalities in Europe make use of the AVAC system, it never caught on in the U.S.

But Walt Disney World isn’t the sole owner of a stateside trash tube system. Around the same time, a few states away, another grand experiment in community planning was taking place on Roosevelt Island in New York. It may not have a monorail, but it does have an AVAC.

The article, with photos to demonstrate the process. (Photo: Courtesy IEHA)

Walt Disney World’s AVAC was indeed the success they predicted in their pre-opening fanfare. In a 1972 Los Angeles Times article (Headline: “In Newest ‘Magic Kingdom’ Even the Garbage Vanishes”) a reporter went behind the scenes of what they cheekily dubbed “Garbage Land”.

The report described a $1 million, two-mile network of underground tunnels with 16 collection points throughout the park. Trash zipped at 60 miles per hour through 20-inch pipes to a central collection area where it was compressed and incinerated. The system proved its mettle on Thanksgiving when it processed 56,000 pounds of trash.

A 1965 photograph showing Walt Disney and his brother Roy with Florida’s Governor W. Haydon Burns, announcing plans to create a Disney theme park in the state. Walt Disney World opened in 1971. (Photo: Public Domain)

It was installed as part of the park’s “Utilidor” network, a kind of city beneath a city that allows the park to carry out operations without disturbing the perfectly calibrated flow of fun above. The Utilidor system has become such a source of fascination for park-goers that it has been folded into a five hour behind-the-scenes tour that promises to show guests the tunnels that “allow Cast Members, deliveries and even rubbish to be unknowingly transported below Guests’ feet as they wait in line for their favorite attractions.”

Meanwhile, in New York: The same year Disney held its press conference heralding Walt Disney World, the city of New York leased a sliver of an island in the East River to the Urban Development Corporation. Previously used as a site for a prison, an asylum, and hospitals, a plan was put into motion to build a residential community from scratch on Roosevelt Island. Like Walt Disney World, this provided ample opportunity to improve things planners felt were lacking in organically developed communities. The island would be virtually car free (residents could park vehicles in a central garage), would feature a European-style promenade good for walking, a variety of housing options to encourage diversity, a student-focused public school system and buildings designed by prominent architects. And an AVAC.

A view of the Queensboro Bridge across Roosevelt Island, c. 1970s. (Photo: Library of Congress/HAER NY,31-NEYO,160)

An AVAC would be clean, hidden from sight, and cheaper than other waste disposal options, according to a 1970 report addressed to the Roosevelt Island planners. Plus, it would be a “utilization of the newest technology.” There weren’t any AVAC systems in U.S. residential neighborhoods, the authors pointed out—but there was one in Walt Disney World. And the men who built that system could install one like it on the island.

Today, some of the lofty goals set for Roosevelt Island haven’t quite come to pass. A 2014 report from Columbia University declared the quest for diversity “not entirely as successful as planned,” and cars are much more a part of island life than its designers hoped. But it is an architectural hotspot and in 2017 Cornell University will open the first phase of an ambitious new tech campus on the island.

But the AVAC did work. Roosevelt Island is a magical land devoid of curbside garbage bags and noisy garbage trucks.

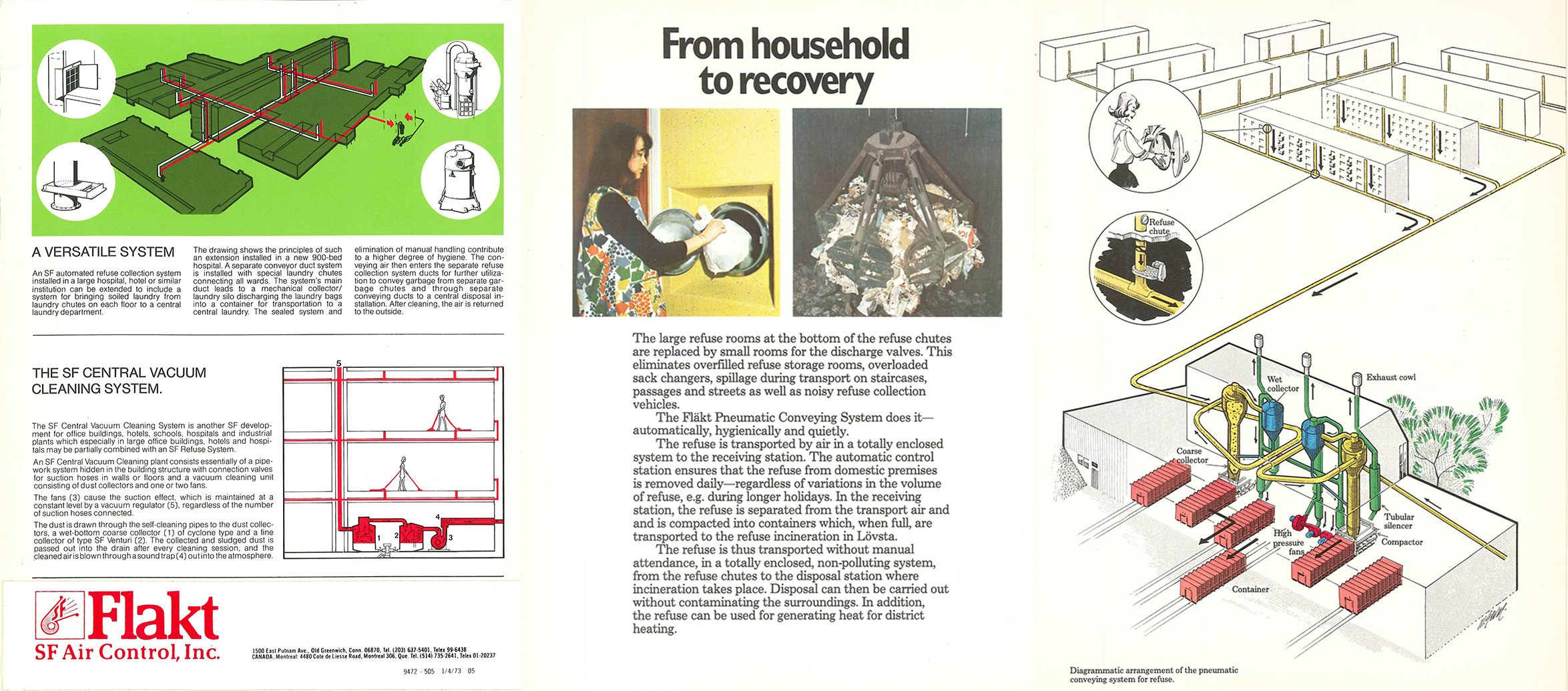

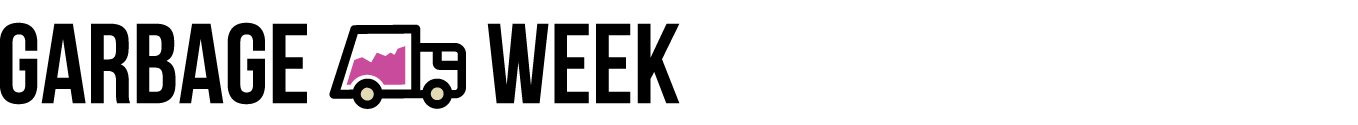

A brochure from Flakt SF Air Control Inlt, a Swedish manufacturer of AVAC systems. (Photo: Courtesy Envac)

The island’s system handles all residential waste via chutes installed in local apartment buildings. The system zips several tons of trash daily to a compacting center where it’s loaded into containers and picked up by the NYC Department of Sanitation. Occasionally, people abuse the system, according to a 2010 documentary, shoving things like Christmas trees, cinder blocks, and—in a kind of meta trash situation— vacuums, into the chutes. These cause jams that a human must locate and fix.

Jams aside, islanders seem to love their celebrity trash system. The AVAC has scored New York Times and New Yorker profiles, starred in many a film, and was the subject of an exhibition called “Fast Trash”.

The interior of the brochure. (Photo: Courtesy Envac)

Popularity aside, AVAC’s didn’t spread across the country. Some cities, such as Carmel, Indiana, proposed ambitious projects, but nothing stuck. Internationally, European cities such as Barcelona and Stockholm claim pneumatic trash networks, but stateside, the sole owners remain Roosevelt Island and Walt Disney World, two utopian experiments united by garbage.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook