A Digital Look at Darwin’s Trove of Prehistoric Fossils

London’s Natural History Museum is putting the naturalist’s haul of skulls, molars, and more online.

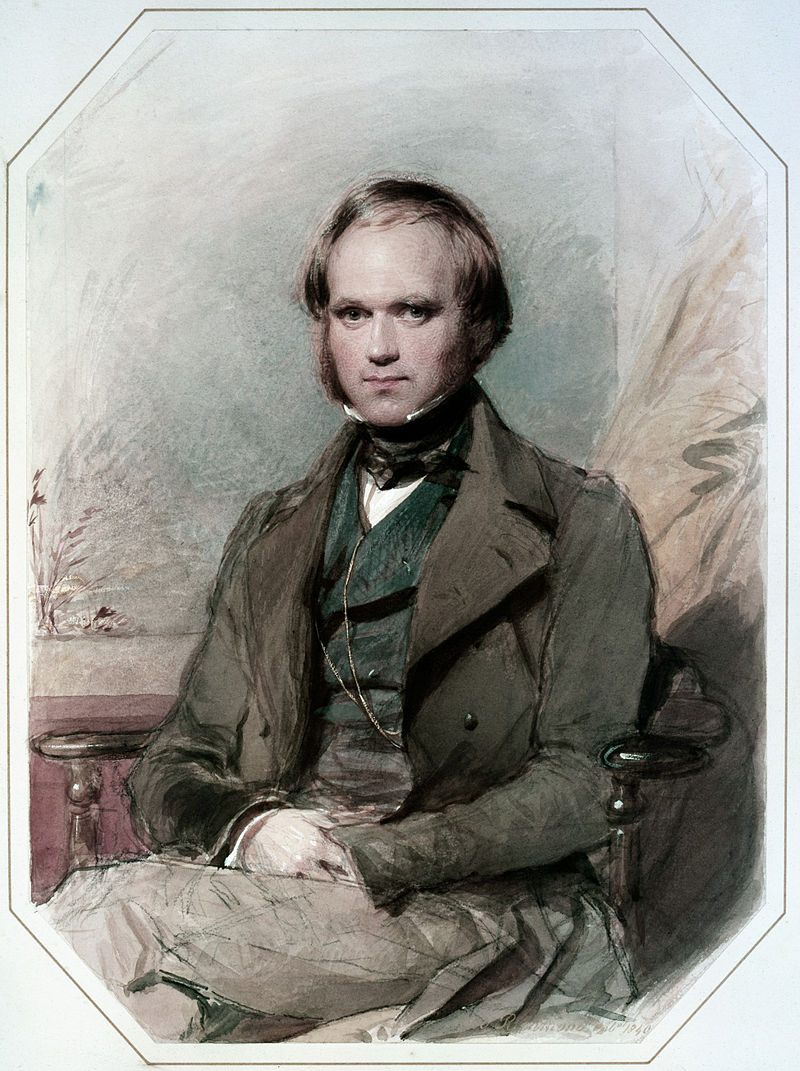

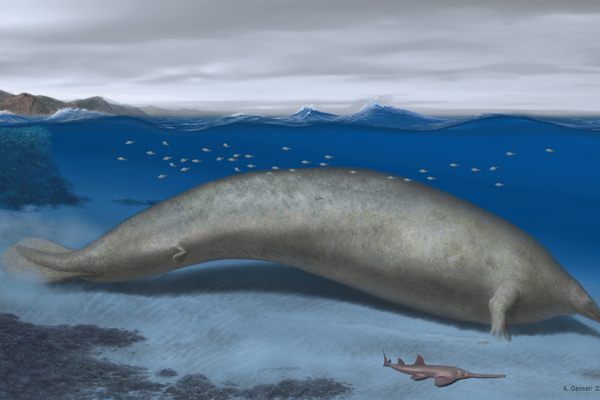

The year was 1832. It was decades before Charles Darwin would compile his field notes into a treatise on natural selection, and the naturalist was obsessed with fossils. On the second day ashore at Punta Alta, Argentina, Darwin didn’t return to the Beagle until long after nightfall. He was busy poking and prodding at a cliff—and when he did finally board, it was with a new shipmate: the fossilized skull of Megatherium, a massive ground sloth roughly the size of a modern elephant.

As the ship drifted from one South American port to another, Darwin stockpiled mandibles, molars, skulls, and other bones. Many of these he extracted from rocks himself, or with the help of his shipmates. A few others were purchased. A shilling and a sixpence seemed like a fine price to pay for a skull from Toxodon platensis—a rhino relative—purchased from a now-unknown owner on a farm in Uruguay. When it surfaced in a stream after a deluge, “locals believed it to be giant’s bones,” says Jennifer Pullar of the digital collections team at London’s Natural History Museum. Afterwards, “children had been using the skull as target practice using stones to knock out its teeth.”

Darwin’s haul of fossils made its way back to England, and fanned out to different collections. The Megatherium ended up at the Royal College of Surgeons, with a slice going to Down House, Darwin’s home. The Toxodon skull, along with 100 other bones or fragments, landed at the Natural History Museum—and now, the museum is putting it online, part of a series of high-res 3D images to be perused by visitors and researchers alike.

The first scans went up this week. Richly detailed digital versions will open up an avenue for researchers or curious clickers to scrutinize the fragile fossils from a distance—and free up the museum to destroy small portions of the originals to perform DNA analysis.

The project also highlights just how wondrous Darwin found fossils to be. In a new book, Darwin’s Fossils: The Collection That Shaped the Theory of Evolution, Adrian Lister, a researcher in Earth sciences at the Natural History Museum, chronicles Darwin’s fascination. “I have just got scent of some fossil bones of a Mammoth,” the naturalist wrote in a letter. “What they may be, I do not know, but if gold or galloping will get them, they shall be mine.”

In a letter to his sister Caroline, Darwin marveled at the way fossilized bones “tell their story of former times with almost a living tongue.” Years later, under the gaze of more sophisticated imaging technologies, the fossils have fresh tales to tell.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook