A Fossilized Skull May Solve the Mystery of a Chameleon Migration

A raft very likely carried chameleons between Madagascar and mainland Africa—but in which direction?

Millions of years ago, at least one chameleon likely surfed the seas between the island of Madagascar and mainland Africa. This voyage was probably not a conscious decision. “Chameleons did not want or plan to raft to Madagascar like some sailors,” says Andrej Čerňanský, a paleontologist at Comenius University in Bratislava, Slovakia, writes in an email. “These things happened accidentally.” But in this happy accident, the chameleon or chameleons survived the surf to crawl on the shores of a distant land.

Most herpetologists agree on the theory that a chameleon once crossed the portion of the Indian Ocean that separates Madagascar from the mainland. But they disagree on an important question: did the voyage begin on the island or the mainland? A new study by Čerňanský, recently published in Scientific Reports, supports the claim that chameleons originated on the mainland.

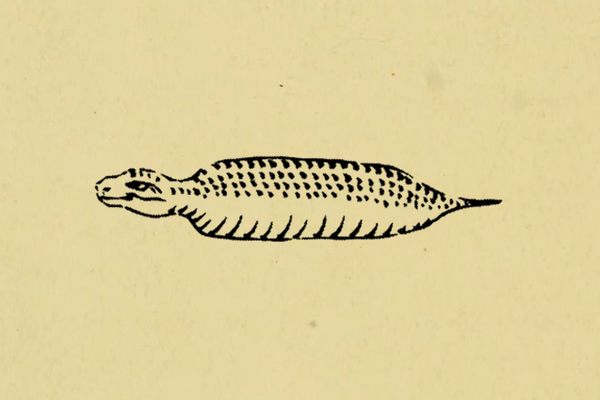

Chameleons—the wacky-looking family of lizards with swiveling eyes, petal-shaped hands, and often color-changing abilities—have a murky origin story. There are 213 known chameleon species, approximately half of which are found on Madagascar. This unusual biodiversity inspired a widely held theory that chameleons originated on the island before floating to mainland Africa on tree rafts, according to Čerňanský. But chameleon fossils are rare, making it hard to prove any theory of the family’s origin. “Almost all species are arboreal and the fossilization processes in forest environments are extremely difficult,” Čerňanský says. And the chameleon fossils that do survive are often fragmented, such as an isolated jaw or part of a skull.

Madagascar became an island around 150 million years ago, during the last gasps of the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana, Čerňanský says. This was before the dinosaurs died off, but before chameleons evolved. In 2002, Christopher Raxworthy, a herpetologist at the American Museum of Natural History, suggested in a paper for Nature that chameleons left Madagascar on several separate occasions and migrated across the ocean to mainland Africa. In 2013, Krystal Tolley, a molecular ecologist at South African National Biodiversity Institute in Cape Town, and two co-authors published a study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences that analyzed chameleon genetics and found the opposite: that chameleons may have originated in mainland Africa.

In Čerňanský’s eyes, Tolley’s study made sense, but it was missing fossil evidence. He wanted to study one particular chameleon skull, which was found in the 1990s on Rusinga Island, a famed fossil site in Kenya. “Everybody knows that it is a very important piece of the chameleon history, because it is a complete three dimensionally preserved skull,” Čerňanský writes. But the skull was still partially trapped in rock, and the researchers who originally described it in 1992 did not have the technology that would have allowed them to see the whole skull. Čerňanský could not take the skull to Germany, where he worked at the time, to run it through a micro-CT scanner, because Kenya had enacted strict laws against colonial plundering. He finally got his skull scan with the help of Job Kibii, a paleontologist at the National Museums of Kenya.

The micro-CT scan produced an x-ray image of the entire structure of the skull, which suggested that it came from a new species in the genus Calumma, endemic to Madagascar. Čerňanský believes that this proves Calumma lived on continental Africa in the past, and provides strong evidence for an African origin for Madagascar chameleons. Olivier Rieppel, an evolutionary biologist at the Field Museum who wrote the first observational study of the Kenyan skull in 1992 and was not involved in Čerňanský’s study, finds the new study convincing. “Multiple dispersal events of chameleons out of Madagascar in different directions just seemed counterintuitive,” he says. “An African mainland origin of chameleons seems more plausible, and honestly, fits my intuition better.”

Miguel Vences, a herpetologist at the Technical University of Braunschweig in Germany who co-authored the 2013 study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences that suggested chameleons originated in Africa, has doubts, even though Čerňanský’s study would support his paper. “There are several hints in the paper that suggest the skull is quite similar to African species such as Chamaeleo dilepis,” he writes in an email, referring to the flap-neck chameleon, one of the most common chameleon species in sub-Saharan Africa. In Vences’ eyes, there isn’t enough evidence to rule out the possibility that the skull could have come from an extinct ancestor of Chamaeleo, as opposed to from a species in Calumma.

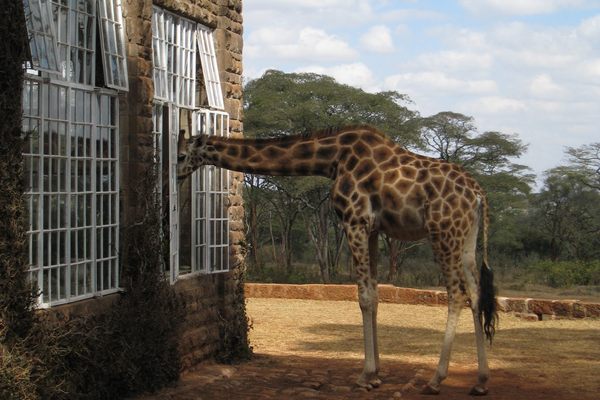

Rafting is perhaps the best known method of oceanic dispersal, in which terrestrial organisms float across the sea from one landmass to another. Scientists believe many species colonized new lands this way millions of years ago, from long-tailed skinks to flightless weevils. In 1998, scientists observed 15 iguanas—enough to start a new population—floated 200 miles across the Caribbean Sea after a hurricane, according to The New York Times. “Chameleons live on trees and when a tree falls down into the ocean, it takes all “passengers” on it,” Čerňanský says. Chameleons are not particularly good at swimming, so Čerňanský consulted paleo-oceanographic models of the currents between Africa and Madagascar, which maps out how oceanic currents might have flowed in the past. He found that currents would have flowed to the east, toward Madagascar, making it seem likelier that a bad swimmer like a chameleon could have been carried to the island’s shores intact.

The fossilized skull in question is now on public view in the paleontology hall of the Nairobi National Museum.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook