How the Design of Dice Evolved Over Time

2,000 years of dicey odds.

Think of all the games that would be impossible to play without dice. Dungeons and Dragons, Yahtzee, craps, and backgammon are just a few examples. Whether its a dodecahedron or octahedron, a uniform die gives us a fair shot at winning a play or sadly losing another bet. Yet, a new anthropological study found that dice weren’t always all that uniform.

The earliest dice can be traced back to 6000 B.C. in Mesopotamia, and were often used to tell fortunes. Ancient Egyptians played one of the oldest known board games called Senet with dice, and during the Tang Dynasty in China, people gambled using dice. Back then, people carved the objects into conical or knucklebone-like shapes from horse hooves or bone. It was not until the Roman Empire that the predominance of cubic dice emerged.

Excavating dice is a matter of odds. They aren’t found in archaeological sites, like fossils or prehistoric tools are. Rather, dice are commonly found in the deep innards of trash bins or graveyards. For archaeologists, these are perfect places to find what people leave behind in the past.

The study’s co-authors, Jelmer Eerkens from University of California, Davis, and Alex de Voogt from the American Museum of Natural History, analyzed 110 dice from museums and depots across the Netherlands and cross-compared them to 62 dice from the United Kingdom. Their findings, which were published in Acta Archaeologica, uncovered a surprising evolution over the centuries.

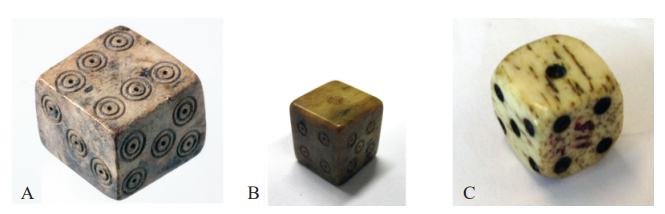

According to the study, cubic dice created around or before 400 B.C., in the Roman era, were misshapen and asymmetrical trinkets made from ivory, metal, or wood, with the numbers one through six on the faces. Opposing sides for six-sided cubic dice added up to seven. Roman dice makers relied on this general cuboid template, but put an individual spin on each die design. That’s why Roman era dice came in diverse variations. As for the asymmetry of dice options back then, researchers aren’t sure if designers were motivated by a desire to manipulate games or by the concept of fate. If fate decided the outcome of games, it didn’t matter that the dice weren’t symmetrical.

By 1100, there was some dice standardization and a size decrease, but Roman dice largely remained lopsided throughout the early medieval times. One major shift did occur though. The numbers on the sides appeared in an arrangement where opposite faces equated to prime numbers. For instance, five and six would sit opposite one another, because they add up to the prime number eleven.

“We don’t really have a good idea why that [change] happened or what caused that shift, but we see it both in the U.K. and the Netherlands. So, it was something people must have agreed upon,” Eerkens says.

Around 1450, the Renaissance ushered in a new set of novel philosophies and beliefs. Great thinkers such as Galileo and Blaise Pascal conceptualized theories about probability and chance, using gamblers as research. This ideological change also translated to how people sculpted dice, which had disappeared during the Dark Ages and materialized once again.

“We think users of dice also adopted new ideas about fairness, and chance or probability in games,” said Eerkens in a statement. The numbering style changed from the prime number configuration (1-2; 3-4; 5-6), one heavily influenced by popular ancient Egyptian numerical arrangements, back to the style “where opposite sides add up to seven (6-1; 5-2; 3-4).” Eerkens suggests that while the direct cause for this shift is unclear, it could possibly be related to an gradual effort to make fair and balanced dice.

By the late 1600s, as dice lost favor to card games, the study suggests, “gamblers may have seen dice throws as no longer determined by fate, but instead as randomizing objects governed by chance.” In Northwestern Europe, people exchanged cultural ideas and information on what a die should look like. From this cultural transmission, people developed standard practices and rules for die manufacturing.

Therefore, a standardized symmetrical die shape developed en masse as people’s beliefs about fairness, randomness, and chance advanced. The pips—the dots on the sides of dice—also changed from a “dot-ring-ring pattern to simple dots,” the design we know today. The pip redesign is less related to the changing worldview, but Eerkens surmises that it could be related to dice size. Eerkens explains that from 1100 until the Renaissance, gambling and dice usage was illegal. He theorizes that black market dice manufacturers carved smaller dice and pips so people could efficiently hide them.

Eerkens and de Voogt acknowledge that their research is just the beginning. The goal is to use this study to increase the sample size well beyond the Roman period, expand research outside Europe, and assist future studies. The researchers conclude the data, most importantly, offers information “on cultural transmission processes in northwest Europe.” People migrating throughout Europe were influenced by different styles and ideas, and then incorporated those aspects into dice design.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook